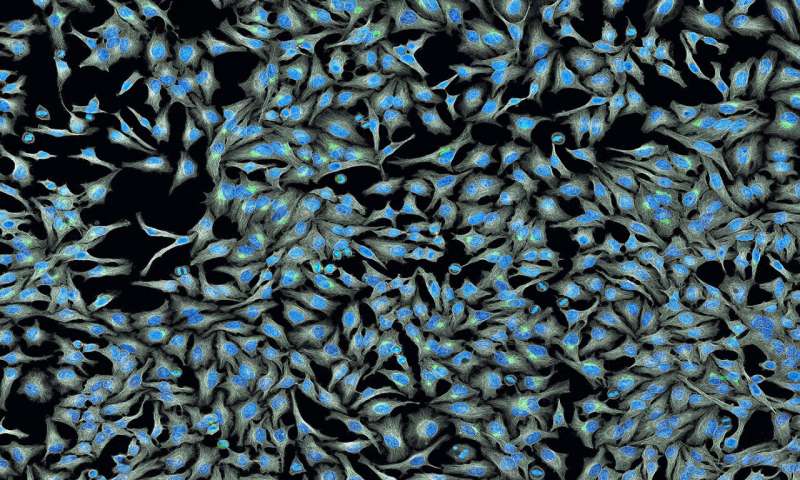

Despite tremendous advances in medicine, tumors are challenging to cure because they are made up of heterogeneous cells. In other words, like human families, the individual cells of a tumor share some common traits and characteristics, but as the tumor expands, the cells also develop their own identities. And, as a result, some cells are more resistant to therapy than others and quicker to adapt and change.

A team of researchers from UT Austin’s Cockrell School of Engineering and College of Natural Sciences, including integrative biology postdoctoral researcher Kaitlyn Johnson, developed a new way to tag tumor cells to figure out how they evolve and change over time to resist cancer treatments. They studied chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) primarily, but these findings could help researchers learn more about the entire spectrum of cancerous tumors.

“This is a technology that lets you replay the evolutionary history of the tumor,” said Amy Brock, an associate professor in the Cockrell School’s Department of Biomedical Engineering and co-lead author on a new paper published in Nature Cancer. “We can collect those pre-resistant cells and go back and look at what happened to them. We can try many parallel treatments and measure how specific cells respond and which ones persist.”

The ability to essentially “tag” nucleic acids – the genetic information of the cell such as RNA or DNA – to monitor them is not a brand-new technology. However, current capabilities don’t paint a full picture of how tumor cells evolve. What this platform, known as ClonMapper, can do that wasn’t possible before is look backward and trace how tumor cells change over time. That gives researchers the ability to look at which cells “win out” over less resistant cells, continue to clone themselves and make the tumor more dangerous. By isolating these cells, researchers can better test which treatments do and don’t work against them.

Monitoring changes over time is key to successful transfer treatments. Tumor cells adjust to treatments and become resistant. That’s why patients can go into remission, but later experience relapse.

“This is one of the reasons cancer treatment is so challenging—we don’t have very good ways of predicting ahead of time which cells will be sensitive to a type of drug and which ones will be resistant,” Brock said. “This acquired resistance is a leading cause of treatment failure for many patients with cancer.”

CLL is a low-grade B-cell malignancy that is often monitored for months or even years before it requires active treatment. This “watch and wait” style of treatment relies heavily on accurate monitoring of the patient. In the study, ClonMapper focused on identifying which cells were cloning themselves, how fast this process happened and how it influences the growth rate of surrounding cells over time. This allowed a much more accurate analysis of the cell population and may enable more customized treatment plans for patients.

The ClonMapper study was led by researchers from UT Austin and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School and the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT. The UT Austin team also includes from the Cockrell School and College of Natural Sciences Aziz M. Al’Khafaji, Eric Brenner and Russell E. Durrett.

The UT Austin team is now deploying ClonMapper to study several different cancer types. The Brock lab recently received funding from the National Cancer Institute to study breast cancer and has an ongoing collaboration with Dell Medical School working on colorectal carcinoma treatments.

University of Texas at Austin