Sleep hygiene, which includes practices like providing a cool and quiet sleeping environment or reading before bed time to help kids unwind, is increasingly popular among parents looking to ensure their children get a good night’s rest. But are these practices all they’re cracked up to be? University of British Columbia sleep expert and nursing professor Wendy Hall recently led a review of the latest studies to find out.

“Good sleep hygiene gives children the best chances of getting adequate, healthy sleep every day. And healthy sleep is critical in promoting children’s growth and development,” said Hall. “Research tells us that kids who don’t get enough sleep on a consistent basis are more likely to have problems at school and develop more slowly than their peers who are getting enough sleep.”

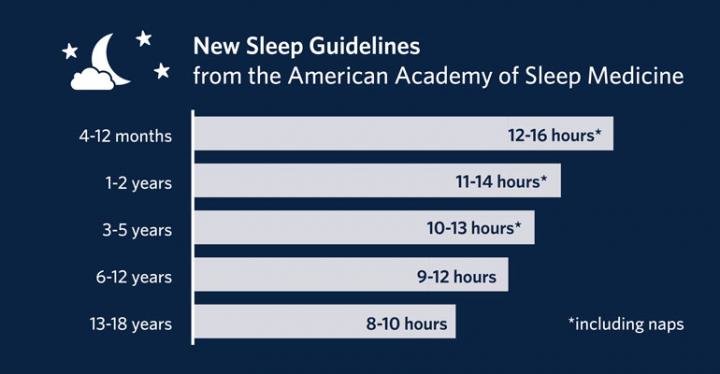

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends the following amounts of sleep, based on age group:

- 4 to 12 months — 12 to 16 hours

- 1 to 2 years — 11 to 14 hours

- 3 to 5 years — 10 to 13 hours

- 6 to 12 years — 9 to 12 hours

- 13 to 18 years — 8 to 10 hours

The UBC review aimed at systematically analyzing the evidence for sleep hygiene across different countries and cultures, and honed in on 44 studies from 16 countries. The focus was on four age groups in particular: infants and toddlers (four months to two years), preschoolers (three to five years), school-age children (six to 12 years) and adolescents (13 to 18 years). These studies involved close to 300,000 kids in North America, Europe and Asia.

“We found good-to-strong endorsement of certain sleep hygiene practices for younger kids and school-age kids: regular bedtimes, reading before bed, having a quiet bedroom, and self-soothing — where you give them opportunities to go to sleep and go back to sleep on their own, if they wake up in the middle of the night,” said Hall.

Even for older kids, keeping a regular bedtime was important. The review found papers that showed that adolescents whose parents set strict guidelines about their sleep slept better than kids whose parents didn’t set any guidelines.

Hall and co-author Elizabeth Nethery, a nursing PhD student at UBC, also found extensive evidence for limiting technology use just before bedtime, or during the night when kids are supposed to be sleeping. Studies in Japan, New Zealand and the United States showed that the more exposure kids had to electronic media around bedtime, the less sleep they had.

“One big problem with school-age children is it can take them a long time to get to sleep, so avoiding activities like playing video games or watching exciting movies before bedtime was important,” said Hall.

Many of the studies also highlighted the importance of routines in general. A study in New Zealand showed family dinner time was critical to helping adolescents sleep.

Information provided by Chinese studies and one Korean study linked school-age children’s and adolescents’ short sleep duration to long commute times between home and school and large amounts of evening homework. With more children coping with longer commutes and growing amounts of school work, Hall says this is an important area for future study in North America.

Surprisingly, there wasn’t a lot of evidence linking caffeine use before bedtime to poor sleep; it appeared to be the total intake during the day that matters.

While Hall said more studies are needed to examine the effect of certain sleep hygiene factors on sleep quality, she would still strongly recommend that parents set bedtimes, even for older kids, and things like sitting down for a family dinner, establishing certain rituals like reading before bed, and limiting screen time as much as possible.

“Sleep education can form part of school programming,” added Hall. “There was a project in a Montreal school where everyone was involved in designing and implementing a sleep intervention — the principal, teachers, parents, kids, and even the Parent Advisory Council. The intervention was effective, because everyone was on board and involved from the outset.”