The spread of invasive cancer cells from a tumor’s original site to distant parts of the body is known as metastasis. It is the leading cause of death in people with cancer. In a paper published online in iScience, University of California San Diego School of Medicine researchers reported engineering sensors that can detect and measure the metastatic potential of single cancer cells.

“Cancer would not be so devastating if it did not metastasize,” said Pradipta Ghosh, MD, professor in the UC San Diego School of Medicine departments of Medicine and Cellular and Molecular Medicine, director of the Center for Network Medicine and senior study author.

“Although there are many ways to detect metastasis once it has occurred, there has been nothing available to ‘see’ or ‘measure’ the potential of a tumor cell to metastasize in the future. So at the Center for Network Medicine, we tackled this challenge by engineering biosensors designed to monitor not one, not two, but multiple signaling programs that drive tumor metastasis; upon sensing those signals a fluorescent signal would be turned on only when tumor cells acquired high potential to metastasize, and therefore turn deadly.”

Cancer cells alter normal cell communications by hijacking one of many signaling pathways to permit metastasis to occur. As the tumor cells adapt to the environment or cancer treatment, predicting which pathway will be used becomes difficult. By comparing proteins and protein modifications in normal versus all cancer tissues, Ghosh and colleagues identified a particular protein and its unique modification called tyrosine-phosphorylated CCDC88A (GIV/Girdin) that are only present in solid tumor cells. Comparative analyses indicated that this modification could represent a point of convergence of multiple signaling pathways commonly hijacked by tumor cells during metastasis.

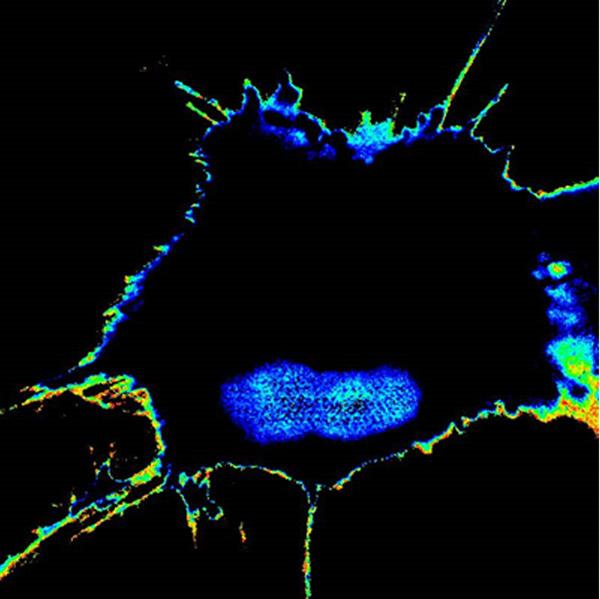

The team used novel engineered biosensors and sophisticated microscopes to monitor the modification on GIV and found that, indeed, fluorescent signals reflected a tumor cell’s metastatic tendency. They were then able to measure the metastatic potential of single cancer cells and account for the unknowns of an evolving tumor biology through this activity. The result was the development of Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) biosensors.

Although highly aggressive and adaptive, very few cancer cells metastasize and that metastatic potential comes and goes, said Ghosh. If metastasis can be predicted, this data could be used to personalize treatment to individual patients. For example, patients whose cancer is not predicted to metastasize or whose disease could be excised surgically might be spared from highly toxic therapies, said Ghosh. Patients whose cancer is predicted to spread aggressively might be treated with precision medicine to target the metastatic cells.

“It’s like looking at a Magic 8 Ball, but with a proper yardstick to measure the immeasurable and predict outcomes,” said Ghosh. “We have the potential not only to obtain information on single cell level, but also to see the plasticity of the process occurring in a single cell. This kind of imaging can be used when we are delivering treatment to see how individual cells are responding.”

The sensors need further refinement, wrote the authors, but have the potential to be a transformative advance for cancer cell biology.