The pneumonia causing pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa has developed a twin-track strategy to colonize its host. It generates two different cells — motile spreaders and virulent stickers. Researchers at the University of Basel’s Biozentrum have now elucidated how the germ attaches to tissue within seconds and consecutively spreads. Just like the business model: settling — growing — expanding. The study has been published in Cell Host & Microbe.

The bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa is one of the most common and dangerous pathogens in hospitals causing severe infections in patients, such as wound infections, pneumonia or meningitis. During the first stage of infection, the pathogen needs to effectively attach to host tissue but at the same time spread to distant sites. At later stages of infection, the pathogen needs to re-adjust its behavior to permanently colonize the host and hide from its immune system, for example, by forming protective biofilms.

From spreading to adhering cells

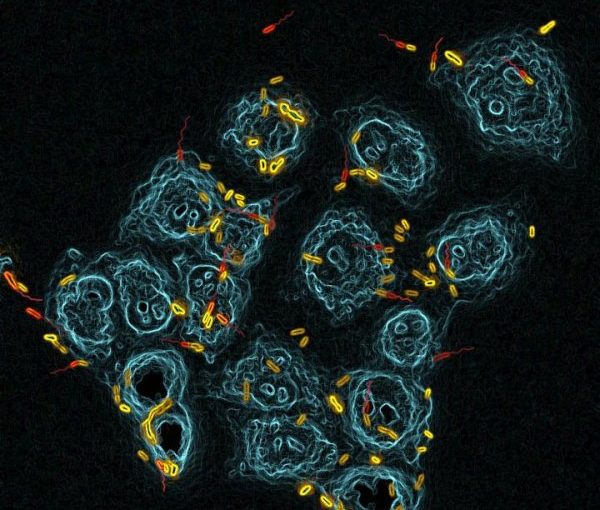

The key to success for P. aeruginosa is its perfected colonization strategy. “During each division, the pathogen generates two distinct cell types, an attacking sticker and a motile spreader,” explains Prof. Urs Jenal, research group leader at the Biozentrum of the University of Basel. “The balance between these two cell types is crucial for the pathogen in order to successfully dwell on tissues and to disseminate rapidly.”

In the initial phase of an infection, the spreader actively moves towards tissue surfaces of the host with a rotating cell propeller, called flagellum. The researchers have now discovered that the flagellum also serves as a mechanical sensor. “When the flagellum encounters a surface, bacteria rapidly respond by producing adhesive protrusions that firmly anchor the bacterium to the tissue,” says Jenal. “We were most surprised by how quickly this happens. Within seconds, the bacteria change their program to stick to the surface.” The tactile stimulus triggers the production of the bacterial signaling molecule cyclic-di-GMP, which in turn initiates the formation of the cell protrusions.

From adhering to spreading cells

Furthermore, the researchers have been able to show that upon division, surface attached bacteria generate two different offspring: one daughter cell remains a sticker that can damage the underlying host tissue, the other one becomes a spreader disseminating to distant sites. This process is also known as asymmetric cell division. “This is due to the asymmetrical distribution of cyclic-di-GMP in the dividing mother cell,” explains first author Benoît Laventie. While the daughter cell with high cyclic-di-GMP level remains attached to the landing site, the cell with low cyclic-di-GMP concentrations leaves the surface to colonize distant sites. Thus, P. aeruginosa exploits a simple business model: first establish, then grow and finally expand.

A smart tactic: conquer and hide

However, there is a limited window of opportunity for P. aeruginosa. After a few asymmetric divisions, the bacteria revert to dividing symmetrically producing exclusively virulent surface-attached offspring, thereby increasing the population at local sites exponentially. The pathogen has changed its strategy and is aiming for long-term establishment in the host and escaping the host’s defense systems.

The researchers in the Jenal lab speculate that this colonization strategy is of a general nature and can be found in a wide variety of bacteria that effectively colonize different surfaces such as stones, shower curtains, coffee cups or human organs.

Story Source:

Materials provided by University of Basel. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.