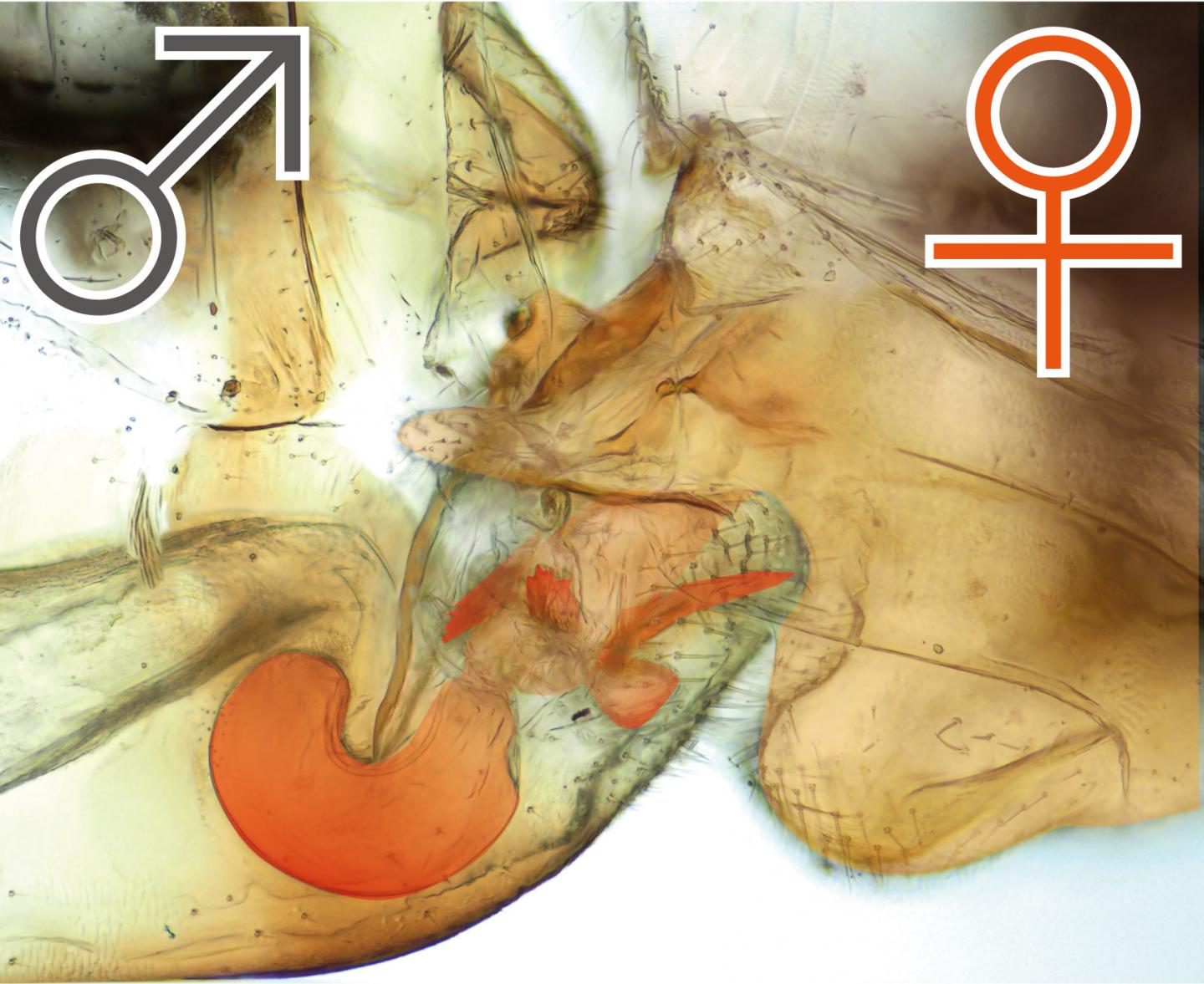

IMAGE: A male (left) and a female (right) of Neotrogla curvata during copulation. The female penis is highlighted in red. Its cashew nut-shaped tip is sclerotized while the basis is inflatable.

Credit: Yoshizawa et al. Biology Letters, Nov. 21, 2018

In a group of bark lice, a penis has evolved twice – in the females. In their nutrient-scarce environment, “seminal gifts” are an incentive for females to force mating, leading to the co-evolution of female penises and male vaginas.

Two geographically distinct genera of the bark lice, Neotrogla in South America and Afrotrogla in southern Africa, have evolved erectable penises in females, according to a study by Associate Professor Kazunori Yoshizawa at Hokkaido University and his group. The team also observed that female penises of Neotrogla have anchoring spines and other morphological differences from the female penises of Afrotrogla, and the males of these species have corresponding pouches in their vaginas. Together with the phylogenetic tree the team constructed for this study, the researchers suggest that the two genera evolved the female penises separately. This study was published in Biology Letters.

The bark lice live in caves that offer extremely scarce sources of nourishment. This gives females an incentive for repeated mating, since the ‘seminal gift’ from males is rich in nutrients. In addition, long mating times of up to 70 hours require females to grasp and stimulate their partners, sometimes even through coercion.

“Of course, one of the important functions of penis and vagina is probably the secure delivery of semen in non-aquatic environments,” Yoshizawa explains. “However, I think sexual selection is a more important factor for the evolution of the ‘male’ penis, because not all terrestrial animals possess it. For example, many birds do not have a penis. Under typical sexual selection in which females are choosy and males are courting, the male penis has evolved many times independently, probably for active and sometimes coercive mating. A simple reversal of gender roles in sexual selection, however, cannot simply cause the reversed genital organs.” In their study, they argue that it is their scarce environment and the competition for male seminal gifts that drove the evolution of female penises in these two groups of bark lice.

The researchers noted that one species of Neotrogla de-escalated the sexual arms race. Their females do not have anchoring spines found in other species of Neotrogla. The researchers argue that this may be due to the bark lice’s particularly dry environment, where potential predators as well as mating competitors are few and thus copulation is less likely to be disturbed. They also speculate that the males in this species may have more control over who they endow with their seminal gifts.

To test hypotheses linking sexual selection pressures, specific environments, and the evolution of penises, it is insightful to study the conditions of species with reversed sexual organs. In the words of Yoshizawa: “The study of female penises could also shed light on the evolution of male penises.”