Researchers at Duke University had 218 dedicated study participants reduce their daily calories by a quarter – though that proved unsustainable for some – for two years. At the end of their extended diets, the participants not only lost weight and kept it off, but their risks for metabolic diseases like diabetes decreased, as did their overall levels of inflammation. Though they can’t say why, the study authors think there’s something about even a little calorie restriction – like skipping dessert – that’s good for us, even if we’re not overweight.

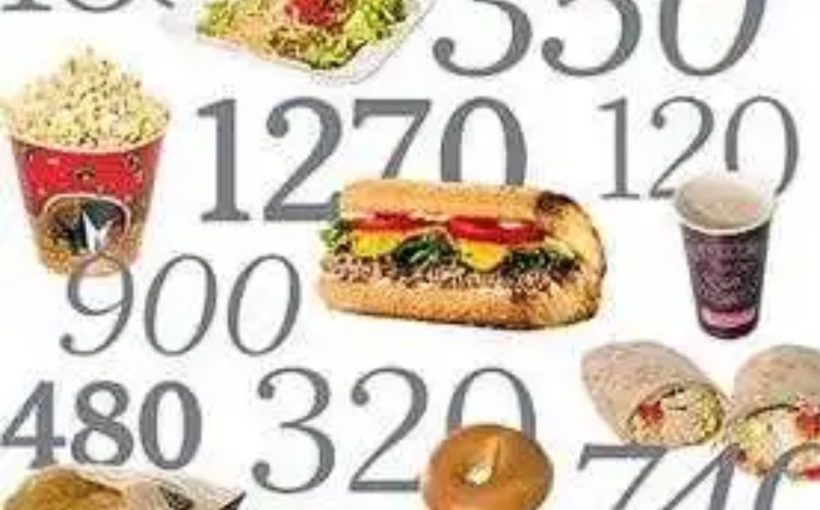

Obesity, excess weight and metabolic diseases have proven to be some of the most damning indicators for Americans’ health. Even before weight problems reach the level of obesity, eating more than we need – especially of highly processed foods, sugars, excessive carbohydrates, fats and red meat – can cause inflammation. Systemic inflammation is commonly linked to the Western diet, and is a significant risk factor in the development of metabolic diseases like diabetes, as well as heart disease, Alzheimer’s, cancer and speed aging in general.

Among the diet strategies being explored to side-step these effects is calorie restrictive eating. On a calorie restriction diet, people – or lab animals, from which we get much of our current data on long-term calorie restriction diets come – people are supposed to get all the same nutrients they would get from their typical meals. Animal evidence suggests that cutting daily caloric intake by 10 to 40 percent may reduce risks of diseases and cancers.

Calorie restriction’s benefits are obvious for people who tend to overeat or have BMIs of 25 or higher. But according to the new research, shaving a few more calories off your meal can be beneficial even if you fall within the healthy weight range. The Duke research team’s 218 recruits were eased into their diets with three daily meals that, in total, contained about 75 percent of their typical daily caloric intake on one of four meal plans. For the first six months of the trial, they also attended regular counseling sessions.

After that initial training period, the researchers asked their subjects to do their best to continue to cut a quarter of their calories out. Most couldn’t quite keep to a diet that strict for two years running. The average participant was able, however, to eat about 12 percent less. Even this more mild diet allowed them to shed and keep off an average of 10 percent of their weight, and 71 percent of that was pure fat. Over the course of those two years, the scientists regularly collected blood, fat, samples from the study participants.

They checked for biomarkers of metabolic syndrome, like insulin resistance, glucose tolerance, high blood pressure, high triglycerides and high cholesterol. Remarkably, after two years of calorie restrictions, these biomarkers suggested reductions in inflammation, and therefore in risks for heart diseases, cancer and cognitive decline, the authors of the study, published in the Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, claim. ‘There’s something about caloric restriction, some mechanism we don’t yet understand that results in these improvements,’ said the study’s lead author Dr William E Kraus, a cardiologist at Duke.

This shows that even a modification that is not as severe as what we used in this study could reduce the burden of diabetes and cardiovascular disease that we have in this country.’People can do this fairly easily by simply watching their little indiscretions here and there, or maybe reducing the amount of them, like not snacking after dinner.’