How does the brain find order amidst a sea of noise and chaos? Researchers at the EPFL Blue Brain Project have found the answer by using advanced simulation techniques to investigate the way neurons talk to each other. In a paper published in Nature Communications, they found that by working as a team, cortical neurons can respond even to weak input against the backdrop of noise and chaos, allowing the brain to find order.

Neurons communicate with each other by sending out rapid pulses of electrical signals called spikes. At first glance, the generation of these spikes can be very reliable: when an isolated neuron is repeatedly given exactly the same electrical input, we find the same pattern of spikes. Why, then, does the activity of cortical neurons in a live animal fluctuate and actually seem so variable?

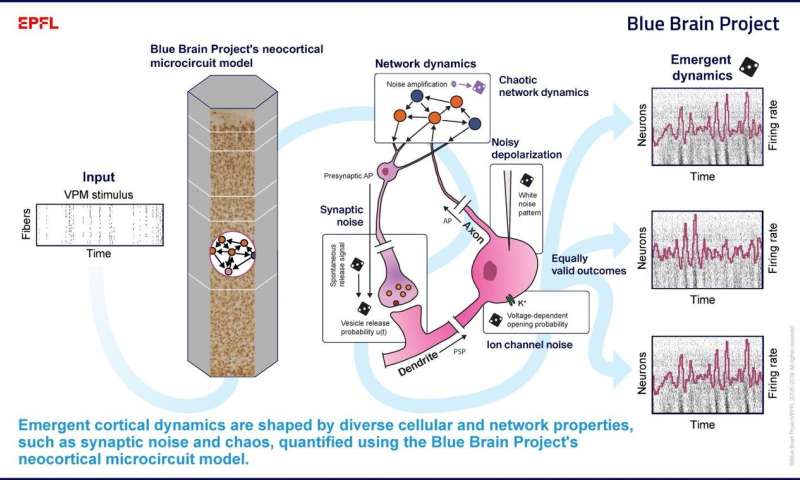

There are two reasons for this. Firstly, when transmitting a signal to another neuron, the process can sometimes fail and these failures are unpredictable—like rolling a die to decide on an outcome. “We estimate the chance of a synapse between two cortical pyramidal neurons passing a chemical neurotransmitter signal can be as low as 10%,” explains lead researcher Max Nolte. This uncertainty means that a neuron will hear the same message sent by connected neurons differently every time.

Secondly, when the two fundamental types of cortical neurons (excitatory and inhibitory) are interconnected in a network, small uncertainties in activity patterns become amplified. This leads to unpredictable patterns, a behavior that is called chaos.

This backdrop of noise and chaos suggests that individual cortical neurons cannot find order and fire reliable spikes, and so the brain has to “average” the activity of many neurons for certainty—listen to the whole choir instead of individual singers.

Simulation neuroscience finds the answer

The experimental manipulations required to untangle the noise sources in the brain and evaluate their impact on neuronal activity are currently impossible to perform in a live animal in vivo, or even in separated brain tissue in vitro. “For the moment, it is simply not possible to monitor all of the thousands of brain-wide inputs to a neuron in vivo, nor to turn on and off different noise sources,” says Nolte. The closest approximation of cortical tissue to date in a model is the Blue Brain Project’s biologically detailed digital reconstruction of rat neocortical microcircuitry (Cell, 2015). This computer model provided the ideal platform for the researchers to study to what degree the voices of individual neurons can be understood, as it contains data-constrained models of the unreliable signal transmission between neurons.

Using this model, they found that activity that is spontaneously generated from the interconnected neurons is highly noisy and chaotic, depicting very different spike times in each repetition. “We studied the origin and nature of cortical internal variability with a biophysical neocortical microcircuit model with biologically realistic noise sources,” reveals Nolte. “We observed that the unreliable neurotransmitter signals are amplified by recurrent network dynamics, causing a rapidly decaying memory of the past—a sea of noise and chaos.”

Reliable responses amidst noise and chaos

But, of course the mammalian brain does not have a rapidly decaying memory. In fact, perhaps the most fascinating insight from the findings is that spike times that were highly unreliable during spontaneous activity became highly reliable when the circuit received external inputs. This phenomenon was not simply a result of strong external input directly driving the neurons to reliable responses. Even weak thalamocortical input could switch the network briefly to a regime of highly reliable spiking. At that point, the interactions between the neurons that otherwise amplify uncertainty and chaos conversely amplify reliability and allow the brain to find order.

“Thalamocortical stimuli can prompt reliable spike times with millisecond precision amid noise and chaos,” explains Blue Brain Founder and Director, Prof. Henry Markram. “Surprisingly, we were able to demonstrate that this effect relies on the cortical neurons working as a team. Our model thus shows that noise and chaos in networks of cortical neurons are compatible with reliable spiking, allowing the brain to find order. This finding suggests that the highly fluctuating activity of cortical neurons in a live animal is reflecting order, not noise and chaos,” Markram concludes.

Source: Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne