The discovery was made using a new state-of-the-art technique developed by researchers in Ilaria Malanchi’s lab at the Crick in order to study the tissue around a tumour—called the tumour microenvironment—known to influence the growth and spread of cancer, as well as treatment response. “Our new technique allows us to study changes to cells in the tumour microenvironment with unprecedented precision,” says Ilaria, who joint-led the project.

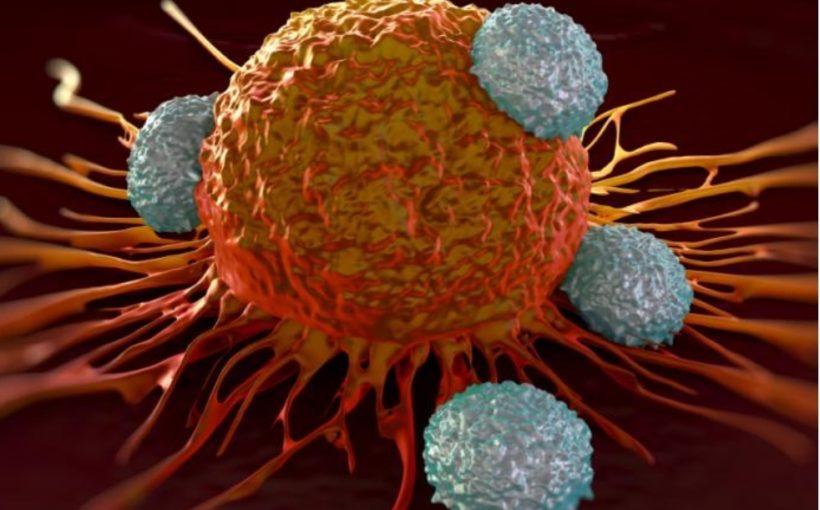

“This helps us to understand how these changes relate to tumour growth and metastasis, allowing us to develop better strategies to treat the disease. “We discovered that non-cancerous cells in the tumour microenvironment regress back into a stem-cell like state, and actually support cancer growth. By corrupting its neighbours, cancer transforms its local environment to support its own survival.

“This new technique relies on cancer cells engineered to release a cell-penetrating fluorescent protein that gets taken up by its neighbouring cells. These colour-labelled cells can be identified and compared to other (unlabelled) cells that have not come into contact with the tumour. Researchers in Ilaria’s lab used this approach in mice to study the cells around breast cancer that had spread to the lungs. Data from Alessandro Ori’s lab at the Fritz Lipmann Institute in Germany confirmed that the labelled cells produced different proteins to unlabelled cells.

The researchers found labelled cells from the lung to have stem cell-like features, unlike the lung cells found outside of the tumour microenvironment. The team showed that those cells from the mouse lungs supported tumour growth when mixed with tumour cells in 3-D culture in the lab, suggesting that they help the cancer to survive and grow. In order to further test the potential of the stem-cell like cells in the tumour microenvironment, Ilaria teamed up with Joo-Hyeon Lee at the Wellcome Trust/MRC Stem Cell Institute, who used them to grow lung organoids, or ‘mini-lungs’.

The unlabelled healthy lung cells formed mini-lungs, mostly made up of alveolar epithelial cells which line the lung’s alveoli—the tiny sacs where gas exchange takes place. By comparison, the labelled cells taken from the tumour microenvironment unexpectedly formed mini-lungs with a wider range of cell types. “To our amazement, we found that cells receiving proteins from adjacent cancer cells obtained stem-cell-like features”, explains Joo-Hyeon Lee, joint senior author of the paper.

“They could change their fate to become different cell types. It demonstrates the powerful influence that cancer exerts over its neighbouring cells, making them liable to change easily. “The researchers hope that their approach will be used by other scientists looking to gain a deeper understanding of the local changes triggered by cancer which help it to survive, spread and develop resistance to treatments. The potential applications are not confined to cancer—a similar approach could enable scientists to study interactions between different cell types in the body.

Source: The Francis Crick Institute