Malaria is one of the world’s deadliest infectious diseases: a small mosquito bite delivers numerous malaria parasites into the bloodstream. The human body defends itself valiantly against the parasite, which usually results in periodic flu-like symptoms and severe fever. Severe cases of the disease are accompanied by tissue damage and result in potentially fatal organ failure. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology in Berlin discovered a possible mechanism behind these complications. The malaria parasite triggers an immune reaction in the bloodstream that is intended for local defense. If the immune response escalates and acts systemically, it damages the patient’s own tissue. This involves a white blood cell type that is highly abundant in the blood: the neutrophil.

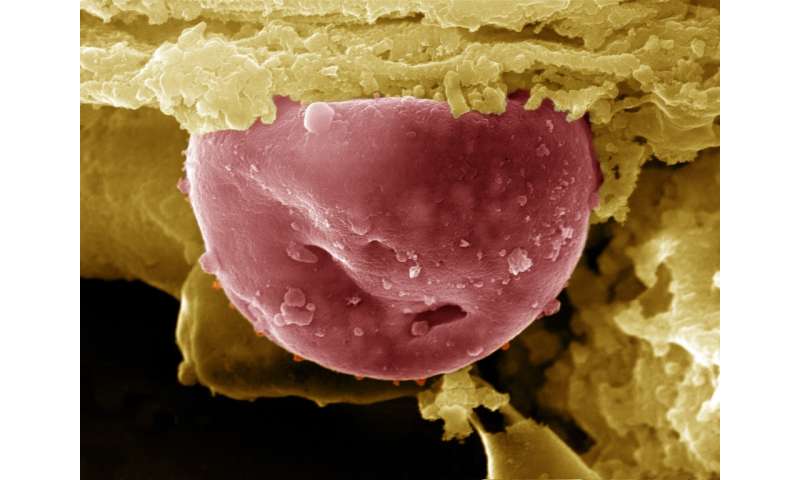

Neutrophils are the most abundant white blood cells. Neutrophils identify and destroy harmful microorganisms that invade our body. Back in 2004, a research group led by Arturo Zychlinsky at the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology discovered a special defense mechanism of neutrophils. The neutrophils react to pathogen contact by committing suicide; they disintegrate their cell and nuclear membrane and release network-like DNA structures that are called neutrophil extracellular traps or NETs. NETs can trap and kill microbes, but they are not only dangerous to the invaders. NETs can also attack the body’s own tissue. It is therefore important that neutrophils are only activated locally and for a limited time.

Researchers from the research groups led by Arturo Zychlinsky and Borko Amulic showed that NETs could cause organ damage in malaria. The findings expand our understanding of typical malaria complications such as liver and kidney failure, pulmonary edema and brain swelling, which can lead to the death of the patient. About half a million people die of malaria every year.

No liver damage without NETs

In order to determine the role of NETs in malaria, the researchers used a special variant of the rodent malaria parasite in mouse experiments. This variant causes liver damage and therefore resembles severe malaria in humans. The researchers first observed a very high concentration of neutrophils and NETs in the blood of the infected mice. To find out if there was a link between NETs and the liver damage, they infected a group of genetically altered mice that could no longer form NETs. This allowed the team of researchers to examine the effect of NETs on disease progression. The results were clear—despite the same parasite burden, the mice without NETs did not develop liver damage.

“We were able to prove that a high concentration of NETs in the blood encourages the attachment of infected red blood cells to vessel walls as well as the recruitment of neutrophils—both are important causes of organ damage in the infected animals,” explains the first author of the now published study, Lorenz Knackstedt. The accumulated blood cells clog the fine vessels in the organs. The lack of oxygen and bleeding from destroyed vessels can lead to total failure of the affected organ.

To show that the findings in the mouse model where relevant in malaria patients, the scientists examined blood samples from Gabon and Mozambique. A clear picture emerged here as well; the number of NETs in the blood increased immensely in cases of severe malaria. “The findings from our mouse experiments and the analysis of patient samples will help us understand malaria and diseases with similar severe symptoms,” states Knackstedt. The described inflammatory responses are also present in systemic diseases like sepsis and systemic lupus erythematosus.

Source: Max Planck Society