With unexpected findings about a protein that’s highly expressed in fat tissue, scientists at Scripps Research have opened the door to critical new understandings about obesity and metabolism. Their discovery, which appears Nov. 20 in the journal Nature, could lead to new approaches for addressing obesity and potentially many other diseases.

The signaling protein, known as PGRMC2, had not been extensively studied in the past. Short for “progesterone receptor membrane component 2,” it had been detected in the uterus, liver and several areas of the body. But the lab of Enrique Saez, Ph.D., saw that it was most abundant in fat tissue—particularly in brown fat, which turns food into heat to maintain body temperature—and became interested in its function there.

An important role: heme’s travel guide

The team built on their recent discovery that PGRMC2 binds to and releases an essential molecule called heme. Recently in the spotlight for its role in providing flavor to the plant-based Impossible Burger, heme holds a much more significant role in the body. The iron-containing molecule travels within cells to enable crucial life processes such as cellular respiration, cell proliferation, cell death and circadian rhythms.

Using biochemical techniques and advanced assays in cells, Saez and his team found that PGRMC2 is a “chaperone” of heme, encapsulating the molecule and transporting it from the cell’s mitochondria, where heme is created, to the nucleus, where it helps carry out important functions. Without a protective chaperone, heme would react with—and destroy—everything in its path.

“Heme’s significance to many cellular processes has been known for a long time,” says Saez, associate professor in the Department of Molecular Medicine. “But we also knew that heme is toxic to the cellular materials around it and would need some sort of shuttling pathway. Until now, there were many hypotheses, but the proteins that traffic heme had not been identified.”

An innovative approach for obesity?

Through studies involving mice, the scientists established PGRMC2 as the first intracellular heme chaperone to be described in mammals. However, they didn’t stop there; they sought to find out what happens in the body if this protein doesn’t exist to transport heme.

And that’s how they made their next big discovery: Without PGRMC2 present in their fat tissues, mice that were fed a high-fat diet became intolerant to glucose and insensitive to insulin—hallmark symptoms of diabetes and other metabolic diseases. By contrast, obese-diabetic mice that were treated with a drug to activate PGRMC2 function showed a substantial improvement of symptoms associated with diabetes.

“We saw the mice get better, becoming more glucose tolerant and less resistant to insulin,” Saez says. “Our findings suggest that modulating PGRMC2 activity in fat tissue may be a useful pharmacological approach for reverting some of the serious health effects of obesity.”

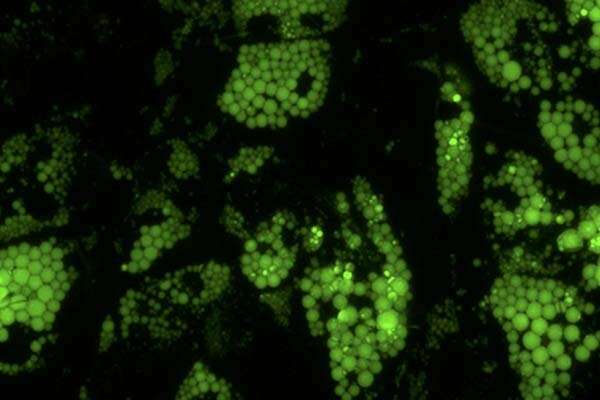

The team also evaluated how the protein changes other functions of brown and white fat, says the study’s lead author, Andrea Galmozzi, Ph.D. “The first surprise finding was that the brown fat looked white,” he says.

Brown fat, which is normally the highest in heme content, is often considered the “good fat.” One of its key roles is to generate heat to maintain body temperature. Among mice that were unable to produce PGRMC2 in their fat tissues, temperatures dropped quickly when placed in a cold environment.

“Even though their brain was sending the right signals to turn on the heat, the mice were unable to defend their body temperature,” Galmozzi says. “Without heme, you get mitochondrial dysfunction and the cell has no means to burn energy to generate heat.”

Saez believes it’s possible that activating the heme chaperone in other organs—including the liver, where a large amount of heme is made—could help mitigate the effects of other metabolic disorders such as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which is a major cause of liver transplantation today.

“We’re curious to know whether this protein performs the same role in other tissues where we see defects in heme that result in disease” Saez says.

The Scripps Research Institute