Researchers at the University of Southampton have identified how new checkpoint inhibitor treatments for cancer can activate tuberculosis in some patients.

Immune therapies for cancer are transforming treatment by activating the body’s immune cells to fight off cancer. Immune checkpoints are part of the human body’s immune system that prevent damaging inflammation, and checkpoint inhibitors are drugs used in immunotherapy to permit the body’s immune system to attack cancer cells.

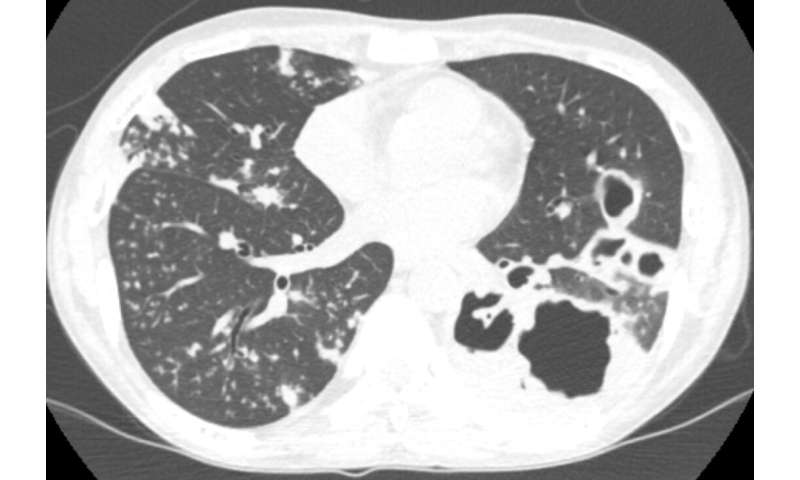

Surprisingly, immune activation with checkpoint inhibitors can sometimes lead to rapidly progressive tuberculosis, an infection that used to kill one in three people in the UK. Researchers in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Southampton described one of the earliest cases of immunotherapy-associated tuberculosis in December 2018 in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, and reports of similar cases have progressively accumulated. However, the true incidence is unknown as progression of cancer and the development of tuberculosis can be similar.

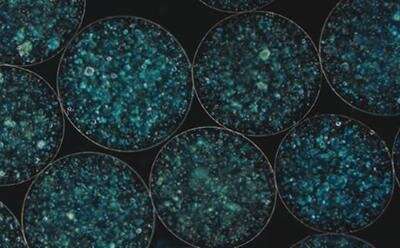

To understand mechanisms underlying this emerging phenomenon, Dr. Liku Tezera, a senior research fellow at the University who led the project, used a 3-dimensional cell culture model to measure the effect of checkpoint inhibitors on the immune system’s ability to control the bacteria that causes tuberculosis disease. The team’s findings, reported in the latest edition of eLife, demonstrate that the addition of an immune checkpoint inhibitor, anti-PD1, led to an excessive immune response, which actually increased growth of the bacteria. The involvement of PD-1 in the natural immune response to TB infection in patients was demonstrated with long-term collaborators based at the Africa Health Research Institute (AHRI), in Durban, South Africa.

“This is an important emerging clinical phenomenon, and by understanding the process that leads to increased tuberculosis growth, we can identify existing treatments that could be used reduce severity of infection and permit continuation of the cancer treatment”, says Dr. Tereza. “This may improve outcomes when this surprising side-effect of emerging cancer immunotherapies occurs”.

The group are currently aiming to establish a national register to capture the true incidence of this phenomenon, and are developing the laboratory system to predict what other new cancer therapies may have a similar effect. The Southampton—Durban team was funded by an MRC Global Challenges Research Fund foundation award to establish sustainable research collaborations to address globally important diseases.

University of Southampton