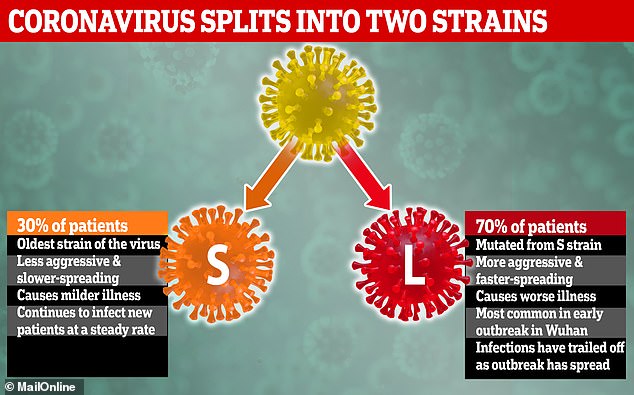

The coronavirus has mutated into at least two separate strains since the outbreak began in December, according to Chinese scientists. Researchers say there are now two types of the same coronavirus infecting people – and most people seem to have caught the most aggressive form of it. At least 94,000 people have been infected around the world and almost 3,200 have died, while 50,000 have recovered from the disease.

The team of experts from Beijing and Shanghai said 70 per cent of people have caught the most aggressive strain of the virus but that this causes such bad illness that it has struggled to spread since early January. Now an older, milder strain seems to be becoming more common. Knowing that the virus can mutate may make it harder to keep track of or to treat, and raises the prospect that recovered patients could become reinfected.

The experts cautioned that the study that discovered the mutation only used a tiny amount of data – 103 samples – so more research is needed, and another scientist added that it is normal for viruses to change when they jump from animals to humans. The research was done by experts at Peking University in Beijing, Shanghai University and the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

In their study of genes in 103 samples of the coronavirus, which is named SARS-CoV-2 and causes a disease called COVID-19, they revealed they had discovered two distinct versions of it, which they named L and S. They claimed that around 70 per cent of patients have caught the L strain, which is more aggressive and faster-spreading than S.

But L has become less common as the outbreak has gone on, with it apparently struggling to spread since early January, while S has become more common. S is less aggressive but is thought to be the first strain of the virus which made the jump into humans and is continuing to infect new patients. This could be because the disease it causes is less severe, meaning people carry it for longer before ending up in hospital, increasing the risk of them passing it on.

In the paper the researchers, led by Professor Jian Lu and Dr Jie Cui, said: ‘Whereas the L type was more prevalent in the early stages of the outbreak in Wuhan, the frequency of the L type decreased after early January 2020. ‘Human intervention may have placed more severe selective pressure on the L type, which might be more aggressive and spread more quickly.

‘On the other hand, the S type, which is evolutionarily older and less aggressive, might have increased in relative frequency due to relatively weaker selective pressure. ‘The scientists’ explanation suggests that, because the L strain surged at the beginning of the outbreak and made people so ill, those who caught it were quickly diagnosed and isolated, meaning it had less opportunity to spread widely.

This ‘human intervention’ is thought to be the hospitalisation of people with the virus and the lockdown of areas where it was spreading fast. If people with a certain strain of the virus are taken into hospital faster than those with another strain, this limits the number of other people that strain can infect. A virus must make people ill enough that they spread it through coughing or sneezing, for example, but not so ill that they quickly become bed-bound or die, which would keep them away from other potential victims.

If the virus is prevented from infecting a lot of people, that strain may die off and evolution – via survival of the fittest – will allow another strain which can infect more people to become the dominant one. The S strain may be winning because it causes milder symptoms so patients take longer to realise they’re sick, increasing the risk of them passing it on.

Professor Jian and Dr Jie added: ‘These findings strongly support an urgent need for further immediate, comprehensive studies that combine genomic data, epidemiological data, and chart records of the clinical symptoms of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).’ A British scientist who was not involved with the research said it was too early to say how accurate the claim of the virus splitting into two was.

The University of Leeds’s Dr Stephen Griffin said: ‘It is usually the case that when RNA viruses first cross species barriers into humans they aren’t particularly well adapted to their new host (us!). ‘Thus, they usually undergo some changes allowing them to adapt and become better able to replicate within, and spread from human to human. ‘However, as this study hasn’t tested the relative “fitness” of these viruses when they replicate in human cells or an animal model, it isn’t really possible to say whether this is what’s happened to SARS-CoV2.

‘It is also difficult to say how/why human interference may have impacted upon one strain relative to the other for similar reasons. ‘He added that the difference between the two strains did not offer any insight into how likely someone was to die if they caught it.

Dailymail