Researchers at Princeton University have identified a set of human proteins that the hepatitis B virus (HBV) uses to establish itself permanently inside liver cells. The study, published in the journal Nature Microbiology, could suggest new directions for therapies to treat chronic HBV infection, a condition that increases the risk of developing liver cancer and is responsible for almost 900,000 deaths worldwide each year.

Over 250 million people are chronically infected with HBV. The condition remains incurable and patients currently require lifelong treatment with antiviral drugs that still leave them at an increased risk of developing not only liver cancer but also other liver diseases, including liver cirrhosis.

When HBV first enters its host’s liver cells, its DNA genome contains several gaps and other imperfections that need to be repaired before the virus can establish a permanent infection. To do this, HBV must enlist the help of its host cell’s DNA repair machinery, but exactly which components of this machinery the virus needs has remained a mystery for decades.

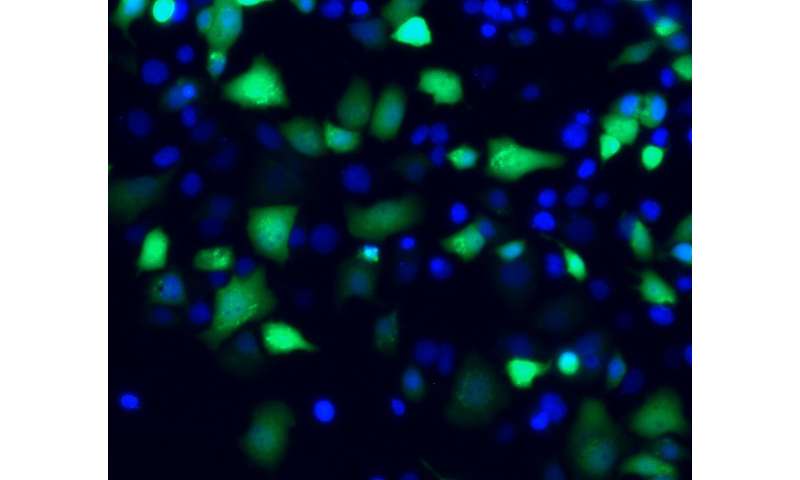

To identify the components required to repair HBV DNA, Alexander Ploss, an associate professor of molecular biology at Princeton, and postdoctoral fellow Lei Wei recreated the process in a test tube. The researchers tested dozens of DNA repair factors and found that a set of just five factors purified from human cells was sufficient for the repair process. Removing even one of these five factors prevented the repair process from being successfully completed, suggesting that targeting any of these five factors can potentially prevent HBV infection.

One of the essential repair factors, an enzyme known as DNA polymerase delta, is inhibited by a drug called aphidicolin. Wei and Ploss found that aphidicolin treatment can prevent the repair of HBV DNA, not only in the test tube but also in virally infected liver cells.

Ploss hopes that further studies will reveal exactly how the five repair factors work together to fix the HBV genome. “Our study is an excellent starting point to finally answer the decades-old question of how the stable form of the virus’s DNA is generated,” Ploss said. “Until we understand this process, which is crucial for HBV persistence, targeted clinical therapies that can completely clear the infection will remain out of reach.”

Princeton University