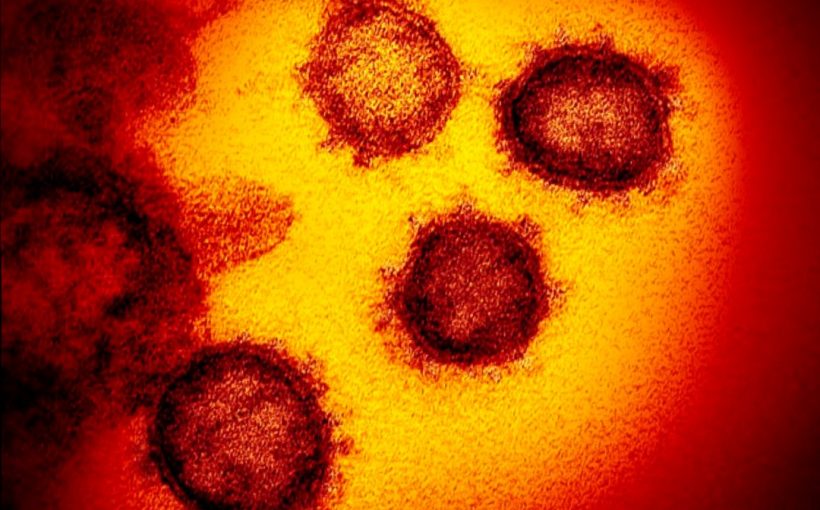

The new coronavirus can live in the air for several hours and on some surfaces for as long as two to three days, tests by U.S. government and other scientists have found.

Their work, published Wednesday, doesn’t prove that anyone has been infected through breathing it from the air or by touching contaminated surfaces, researchers said.

“We’re not by any way saying there is aerosolized transmission of the virus,” but this work shows that the virus stays viable for long periods in those conditions, so it’s theoretically possible, said study leader Neeltje van Doremalen at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Since emerging in China late last year, the new virus has infected more than 120,000 people worldwide and caused more than 4,300 deaths—far more than the 2003 SARS outbreak caused by a genetically similar virus.

For this study, researchers used a nebulizer device to put samples of the new virus into the air, imitating what might happen if an infected person coughed or made the virus airborne some other way.

They found that viable virus could be detected up to three hours later in the air, up to four hours on copper, up to 24 hours on cardboard and up to two to three days on plastic and stainless steel.

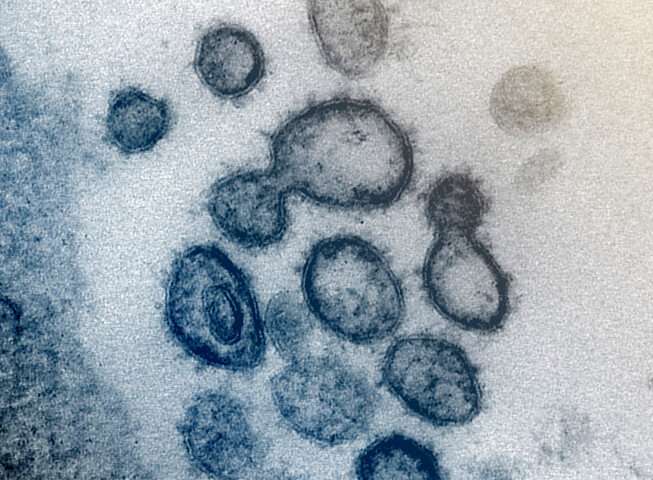

Similar results were obtained from tests they did on the virus that caused the 2003 SARS outbreak, so differences in durability of the viruses do not account for how much more widely the new one has spread, researchers say.

The tests were done at the National Institutes of Health’s Rocky Mountain Lab in Hamilton, Mont., by scientists from the NIH, Princeton University and UCLA, with funding from the U.S. government and the National Science Foundation.

The findings were published on the medRxiv website to discuss work that has not yet been reviewed by other scientists but can be quickly shared with other scientists.

“It’s a solid piece of work that answers questions people have been asking,” and shows the value and importance of the hygiene advice that public health officials have been stressing, said Julie Fischer, a microbiology professor at Georgetown University.

“What we need to be doing is washing our hands, being aware that people who are infected may be contaminating surfaces,” and keeping hands away from the face, she said.

As for the best way to kill the virus, “it’s something we’re researching right now,” but cleaning surfaces with solutions containing diluted bleach is likely to get rid of it, van Doremalen said.