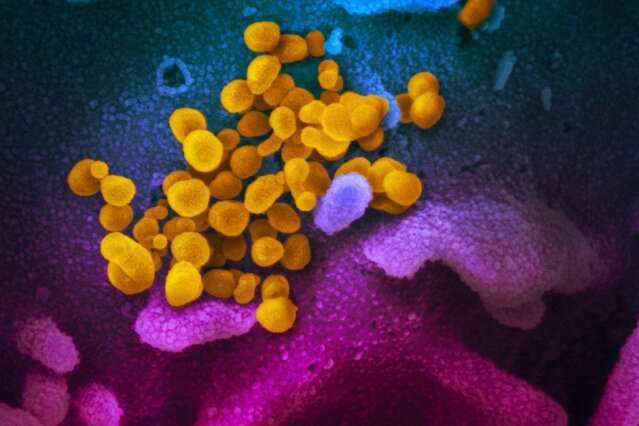

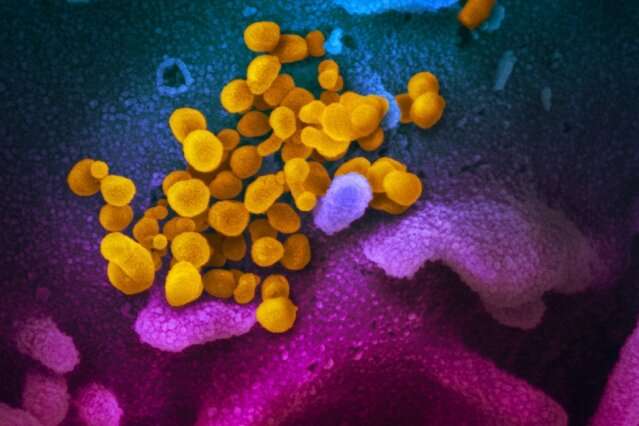

None of the mutations currently documented in the SARS-CoV-2 virus appear to increase its transmissibility, according to a UCL-led study.

The analysis of virus genomes from over 15,000 COVID-19 patients from 75 countries is published today as a pre-print on bioRxiv and has not yet been peer-reviewed.

The findings build on a peer-reviewed study published in Infection, Genetics and Evolution earlier this month that characterized patterns of diversity emerging in the genome of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus causing the ongoing pandemic of the COVID-19 disease.

Lead author Professor Francois Balloux (UCL Genetics Institute) said: “As a growing number of mutations have been documented, scientists are rapidly trying to find out if any of them could make the virus more infectious or deadly, as it’s vital to understand such changes as early as possible.

“We employed a novel technique to determine whether viruses with the new mutation are actually transmitted at a higher rate, and found that none of the candidate mutations appear to be benefiting the virus.”

Coronaviruses, like other RNA viruses, can develop mutations in three different ways: by mistake from copying errors during viral replication, through interactions with other viruses infecting the same cell (recombination or reassortment), or they can be induced by host RNA modification systems which are part of host immunity (e.g. a person’s own immune system).

Most mutations are neutral, while others are advantageous or detrimental to the virus. Both neutral and advantageous mutations can become more common as they get passed down to descendant viruses.

The research team from UCL, Cirad and the Université de la Réunion, and the University of Oxford, have so far identified 6,822 mutations in SARS-CoV-2 across the global dataset. For 273 of the mutations, there is strong evidence that they have occurred repeatedly and independently. Of those, the researchers honed in on 31 mutations which have occurred at least 10 times independently during the course of the pandemic.

To test if the mutations increase the transmission of the virus carrying them, the researchers modeled the virus’s evolutionary tree, and analyzed whether a particular mutation was becoming increasingly common within a given branch of the evolutionary tree—that is, testing whether, after a mutation first develops in a virus, descendants of that virus outperform their closely-related individuals that don’t carry it.

The researchers found no evidence that any of the common mutations are increasing the virus’s transmissibility. Instead, they found that some common mutations are neutral, but most are mildly detrimental to the virus.

The mutations analyzed included one in the virus spike protein called D614G, which has been widely reported as being a common mutation which may make the virus more transmissible. The new evidence finds that this mutation is in fact not associated with increased viral transmission.

The researchers found that most of the common mutations appear to have been induced by the human immune system, rather than being the result of the virus adapting to its novel human host.

First author Dr. Lucy van Dorp (UCL Genetics Institute) said: “It is only to be expected that a virus will mutate and eventually diverge into different lineages as it becomes more common in human populations, but this does not necessarily imply that any lineages will emerge that are more transmissible or harmful.”

University College London