The earliest brain changes due to Huntington’s disease can be detected 24 years before clinical symptoms show, according to a new UCL-led study.

The researchers say their findings, published in The Lancet Neurology, could help with clinical trials by pinpointing the optimal time to begin treating the disease.

There is currently no cure for Huntington’s, a hereditary neurodegenerative disease, but recent advances in genetic therapies hold great promise.

Researchers would ultimately like to treat people before the genetic mutation has caused any functional impairment. However, until now, it was unknown when the first signs of damage emerge—but as there is a genetic test for Huntington’s susceptibility, researchers have a unique opportunity to study the disease before symptoms appear.

Professor Sarah Tabrizi (UCL Huntington’s Disease Centre, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology), the study lead, said: “Ultimately, our goal is to deliver the right drug at the right time to effectively treat this disease—ideally we would like to delay or prevent neurodegeneration while function is still intact, giving gene carriers many more years of life without impairment.

“As the field makes great strides with the drug development, these findings provide vital new insights informing the best time to initiate treatments in the future, and represent a significant advance in our understanding of early Huntington’s.”

The Wellcome-funded study, led by UCL researchers in collaboration with colleagues from the University of Cambridge and University of Iowa, investigated a large cohort of Huntington’s mutation carriers at a much younger age than previously examined in detail. 64 people with the mutation took part alongside 67 others without the mutation who served as control subjects for comparison.

The study involved the most extensive testing of Huntington’s ever performed, including tests of thinking, behaviour, brain scans and proteins in spinal fluid.

The mutation carriers were, on average, 24 years ahead of the predicted disease onset, based on their age and a genetic test. They exhibited no changes in thinking, behaviour or involuntary movements commonly found in the disease, and there was very little evidence of brain scan changes.

But researchers did detect a subtle increase in the spinal fluid of a neuronal protein called neurofilament light (NfL), which is often the product of nerve cell damage.

Just under half (47%) of the mutation carriers had NfL values in their spinal fluid above the range of values found in the control group, at 24 years before disease onset, suggesting the authors have identified a crucial point at which brain changes first start occurring. NfL values correlated with predicted time to disease onset. The finding was supported by using the data to model predicted trajectories.

Co-first author of the study, Dr. Paul Zeun (UCL Huntington’s Disease Research Centre) said: “We have found what could be the earliest Huntington’s-related changes, in a measure which could be used to monitor and gauge effectiveness of future treatments in gene carriers without symptoms.”

Co-first author of the study, Dr. Rachael Scahill (UCL Huntington’s Disease Research Centre) added: “Other studies have found that subtle cognitive, motor and neuropsychiatric impairments can appear 10-15 years before disease onset. We suspect that initiating treatment even earlier, just before any changes begin in the brain, could be ideal, but there may be a complex trade-off between the benefits of slowing the disease at that point and any negative effects of long-term treatment.”

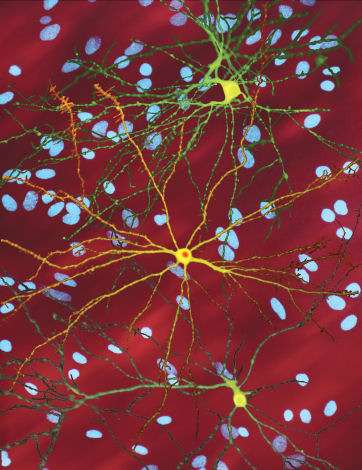

Huntington’s disease is caused by a single known genetic mutation, which codes for the production of the toxic mutant huntingtin protein that slowly damages neurons in disease sufferers. The disease usually develops in adulthood and causes abnormal involuntary movements, psychiatric symptoms and dementia. Patients usually die within 20 years of the start of symptoms.

Approximately 10,000 people in the UK have Huntington’s, and a further 50,000 people are at risk of carrying the Huntington’s genetic mutation. Each child of a mutation carrier has a 50% chance of inheriting the disease.

No effective treatments exist to slow it down. Professor Tabrizi led the first human safety trial, completed in 2017, of a drug developed to reduce the levels of the huntingtin protein in the nervous system, which successfully lowered levels of the toxic huntingtin protein in participants. She is now one of the lead investigators on a major global phase 3 clinical trial, testing the long-term safety and clinical efficacy of the drug, and whether it slows disease progression.

University College London