Cancer cells are comfy havens for bacteria. That conclusion arises from a rigorous study of over 1,000 tumor samples of different human cancers. The study, headed by researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science, found bacteria living inside the cells of all the cancer types—from brain to bone to breast cancer—and even identified unique populations of bacteria residing in each type of cancer. The research suggests that understanding the relationship between a cancer cell and its “mini-microbiome” may help predict the potential effectiveness of certain treatments, or may point to ways of manipulating those bacteria to enhance the actions of anticancer treatments in the future. The findings of this study were published in Science.

Several years ago, Dr. Ravid Straussman of the Institute’s Molecular Cell Biology Department had discovered bacteria lurking within human pancreatic tumor cells; these bacteria were shown to protect cancer cells from chemotherapy drugs by “digesting” and inactivating these drugs. When other studies also found bacteria in tumor cells, Straussman and his team wondered whether such hosting might be the rule, rather than the exception. To find out, Drs. Deborah Nejman and Ilana Livyatan in Straussman’s group and Dr. Garold Fuks of the Physics of Complex Systems Department worked together with a team of oncologists and researchers around the world. The work was also led by Dr. Noam Shental of the Mathematics and Computer Science Department of the Open University of Israel.

Ultimately, the team would produce a detailed study describing, in high resolution, the bacteria living in these cancers—brain, bone, breast, lung, ovary, pancreas, colorectal and melanoma. They discovered that every single cancer type, from brain to bone, harbored bacteria, and that different cancer types harbor different bacteria species. It was the breast cancers, however, that had the highest number and diversity of bacteria. The team demonstrated that many more bacteria can be found in breast tumors compared to the normal breast tissue surrounding these tumors, and that some bacteria were preferentially found in the tumor tissue rather than in the normal tissue surrounding it.

To arrive at these results, the team had to overcome several challenges. For one, the mass of bacteria in a tumor sample is relatively small, and the researchers had to find ways to focus on these tiny cells-within-cells. They also had to eliminate any possible outside contamination. To this end, they used hundreds of negative controls and created a series of computational filters to remove the traces of any bacteria that could have come from outside the tumor samples.

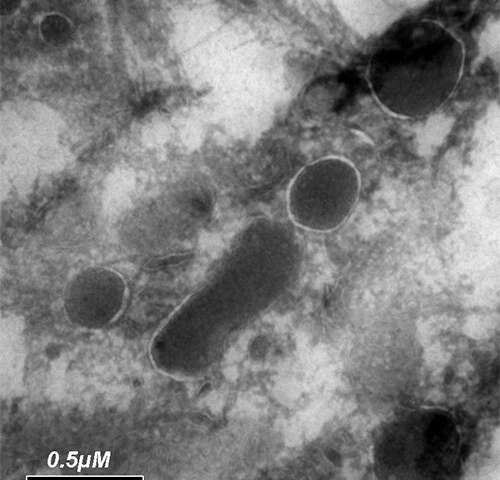

The team was able to grow bacteria directly from human breast tumors, and their results proved that the bacteria found in these tumors are alive. Electron microscopy visualization of these bacteria demonstrated that they prefer to nestle up in a specific location inside the cancer cells—close to the cell nucleus.

Different cells for different bacteria

The team also reported that bacteria can be found not only in cancer cells, but also in immune cells that reside inside tumors. “Some of these bacteria could be enhancing the anticancer immune response, while others could be suppressing it—a finding that may be especially relevant to understanding the effectiveness of certain immunotherapies,” says Straussman. Indeed, when the team compared the bacteria from groups of melanoma samples, they found that different bacteria were enriched in those melanoma tumors that responded to immunotherapy as compared to those that had a poor response.

Straussman thinks that the study can also begin to explain why some bacteria like cancer cells and why each cancer has its own typical microbiome: The differences apparently come down to the choice of amenities offered in each kind of tumor-cell environment. That is, the bacteria may live off certain metabolites that are overproduced by or stored within the specific tumor types. For example, when the team compared the bacteria found in lung tumors from smokers with those from patients who had never smoked, they found variances. These differences stood out more clearly when the researchers compared the genes of these two groups of bacteria: Those from the smokers’ lung cancer cells had many more genes for metabolizing nicotine, toluene, phenol and other chemicals that are found in cigarette smoke.

In addition to showing that some of the most common cancers shelter unique populations of bacteria within their cells, the researchers believe that the methods they have developed to identify signature microbiomes with each cancer type can now be used to answer some crucial questions about the roles these bacteria play: Are the bacteria freeloaders on the cancer cell’s surplus metabolites, or do they provide a service to the cell? At what stage do they take up residence? How do they promote or hinder the cancer’s growth? What are the effects that they have on response to a wide variety of anticancer treatments?

“Tumors are complex ecosystems that are known to contain, in addition to cancer cells, immune cells, stromal cells, blood vessels, nerves, and many more components, all part of what we refer to as the tumor microenvironment. Our studies, as well as studies by other labs, clearly demonstrate that bacteria are also an integral part of the tumor microenvironment. We hope that by finding out how exactly they fit into the general tumor ecology, we can figure out novel ways of treating cancer,” Straussman says.

Weizmann Institute of Science