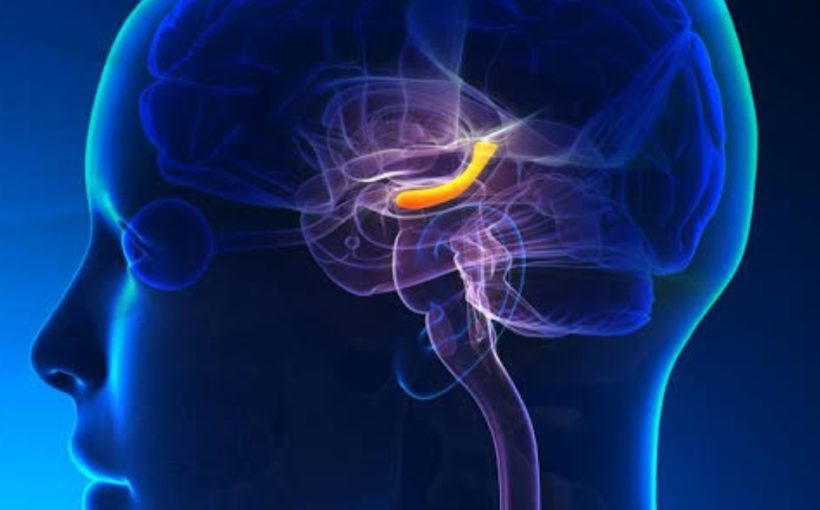

What happens in the hippocampus even before people attempt to form memories may impact whether they remember.

A new study analyzed neuronal recordings from the brains of epilepsy patients while they committed a series of words to memory. When the firing rates of hippocampal neurons were already high before the patients saw a word, they were more successful in encoding that word and remembering it later.

The findings suggest that the hippocampus might have a “ready-to-encode” mode that facilitates remembering. The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences with University of California San Diego researcher Zhisen Urgolites as first author, also suggests that when hippocampal neurons are not already spiking very much, novel information is more likely to be poorly encoded and later forgotten.

“A key question going forward is how to put our brains into ‘encoding mode’ when we wish to do so,” said John Wixted, professor of psychology at UC San Diego, and one of the lead authors on the paper.

“‘Encoding mode’,” Wixted said, “is more than simply paying attention to the task at hand. It is paying attention to encoding, which selectively ramps up activity in the part of the brain that is the most important for making new memories: the hippocampus. Since we know, based on earlier research, that people can actively suppress memory formation, it might be possible for people to get their hippocampus ready to encode as well. But how one might go about doing that, we just don’t know yet.”

Neuronal recordings from the hippocampus, amygdala, anterior cingulate and prefrontal cortex were collected from 34 epilepsy patients while they underwent clinical monitoring at Barrow Neurological Institute. The experiments were originally performed in Peter Steinmetz’s laboratory between 2007 and 2014 when he was at the institute. The data have since been maintained at the Neurtex Brain Research Institute, where Steinmetz is chief scientific officer, and the present research team is newly analyzing the data.

During the experiments, the patients either saw or listened to a steady stream of words and had to indicate whether each word was novel or a repeat. At first, all the words were novel, but after a while most words repeated.

The researchers calculated the average number of times a neuron fired in response to every word the study participants saw or heard. They also calculated the neuronal firing rates immediately preceding each word. Only the average firing rate in the hippocampus approximately one second before seeing or hearing a word for the first time was important: That neuronal activity predicted whether the participants remembered or forgot the word when it was repeated later on.

“If a person’s hippocampal neurons were already firing above baseline when they saw or heard a word, their brain was more likely to successfully remember that word later,” said Stephen Goldinger, professor of psychology at Arizona State University.

The neuronal activity measured in the amygdala, anterior cingulate, and prefrontal cortex did not predict task performance.

“We think new memories are created by sparse collections of active neurons, and these neurons get bundled together into a memory. This work suggests that when a lot of neurons are already firing at high levels, the neuronal selection process during memory formation works better,” Goldinger said.