Cancer researchers at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) have harnessed tools used for the development of cancer immunotherapies and adapted them to identify regions of the SARS-CoV-2 virus to target with a vaccine, employing the same approach used to elicit an immune response against cancer cells to stimulate an immune response against the virus. Using this strategy, the researchers believe a resulting vaccine would provide protection across the human population and drive a long-term immune response.

The strategy is described in Cell Reports Medicine.

“In many ways, cancer behaves like a virus, so our team decided to use the tools we developed to identify unique aspects of childhood cancers that can be targeted with immunotherapies and apply those same tools to identify the right protein sequences to target in SARS-CoV-2,” said senior author John M. Maris, MD, a pediatric oncologist in CHOP’s Cancer Center and the Giulio D’Angio Professor of Pediatric Oncology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. “By adapting the computational tools developed and now refined by lead author Mark Yarmarkovich, Ph.D. in the Maris Lab, we can now prioritize viral targets based on their ability to stimulate a lasting immune response, predicted to be in the vast majority of the human population. We think our approach provides a roadmap for a vaccine that would be both safe and effective and could be produced at scale.”

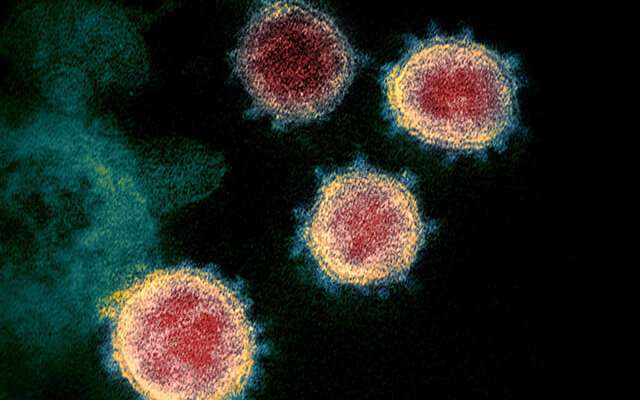

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to an urgent need for the development of a safe and effective vaccine against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes the COVID-19 disease. An optimally designed vaccine maximizes a long-lasting immune response, while minimizing adverse reactions, autoimmunity, or disease exacerbation.

To increase the likelihood that a vaccine is both safe and effective, the research team prioritized parameters in identifying regions of the virus to target. The researchers looked for regions that would stimulate a memory T-cell response that, when paired with the right B cells, would drive memory B cell formation and provide lasting immunity and do so across the majority of human genomes. They targeted regions of SARS-CoV-2 that are present across multiple related coronaviruses, as well as new mutations that increase infectivity, while also ensuring that those regions were as dissimilar as possible from sequences naturally occurring in humans to maximize safety.

The researchers propose a list of 65 peptide sequences that, when targeted, offer the greatest probability of providing population-scale immunity. As a next step, the team is testing various combinations of a dozen or so of these sequences in mouse models to assess their safety and effectiveness.

“With the third epidemic in the past two decades underway, all originating from the coronavirus family, these viruses will continue to threaten the human population and necessitate the need for prophylactic measures against future outbreaks,” said Dr. Yarmarkovich. “A subset of the sequences selected in our study are derived from viral regions that are very similar to other coronaviruses, and thus our approach, if successful, could lead to protection against not only SARS-CoV-2 but also other coronaviruses that might emerge in the future.”

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia