Problems in how the brain recognizes and processes novel information lie at the root of psychosis, researchers from the University of Cambridge and King’s College London have found. Their discovery that defective brain signals in patients with psychosis could be altered with medication paves the way for new treatments for the disease.

The results, published today in the journal Molecular Psychiatry, describe how a chemical messenger in the brain called dopamine ‘tunes’ the brain to the level of novelty in a situation, and helps us to respond appropriately—by either updating our model of reality or discarding the information as unimportant.

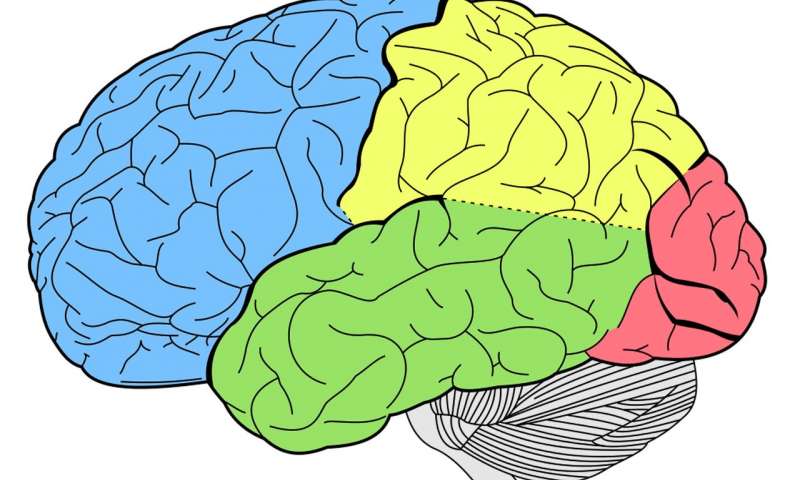

The researchers found that a brain region called the superior frontal cortex is important for signaling the correct degree of learning required, depending on the novelty of a situation. Patients with psychosis have faulty brain activation in this region during learning, which could lead them to believe things that are not real.

“Novelty and uncertainty signals in the brain are very important for learning and forming beliefs. When these signals are faulty, they can lead people to form mistaken beliefs, which in time can become delusions,” said Dr. Graham Murray from the University of Cambridge’s Department of Psychiatry, who jointly led the research.

In novel situations, our brain compares what we know with the new information it receives, and the difference between these is called the ‘prediction error’. The brain updates beliefs according to the size of this prediction error: large errors signal that the brain’s model of the world is inaccurate, thereby increasing the amount that is learned from new information.

Psychosis is a condition where people have difficulty distinguishing between what is real and what is not. It involves abnormalities in a brain chemical messenger called dopamine, but how this relates to patient experiences of delusions and hallucinations has until now remained a mystery.

The new study involved 20 patients who were already unwell with psychosis, 24 patients with milder symptoms that put them at risk of the condition, and 89 healthy volunteers.

Participants were put into a brain scanning machine called a functional MRI and asked to play a computer game. This allowed the researchers to record activity in the participants’ brains as they engaged in situations with a potential variety of outcomes.

In a second part of the study, 59 of the healthy volunteers had their brains scanned after taking medications that act on the signaling of dopamine in the brain. These medications changed the way that the superior frontal cortex prediction error responses were tuned to the degree of uncertainty.

“Normally, the activity of the superior frontal cortex is finely tuned to signal the level of uncertainty during learning. But by altering dopamine signaling with medication, we can change the reactivity of this region. When we integrate this finding with the results from patients with psychosis, it points to new treatment development pathways,” said Dr. Kelly Diederen from the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience at King’s College London, who jointly led the study with Dr. Murray.

In addition to studying brain activation, the researchers developed mathematical models of the choices made by participants in the computer game, to better understand the strategies of how people learn. They found that patients with psychosis did not take into account the level of uncertainty during learning, which may be a good strategy in some circumstances but could lead to problems in others. Learning problems were related to alterations in brain activation in the superior frontal cortex, with patients with severe symptoms of psychosis showing more significant alterations.

“While these kind of abnormal brain responses were predicted several years ago, this is the first time the changes have actually been shown to be present. The results give us confidence that our theoretical models of psychosis are correct,” said Dr. Joost Haarsma from University College London, first author of the study.

University of Cambridge