The first case of the novel coronavirus, COVID-19, in the United States was in late January. By mid-March, “social distancing” had entered the public lexicon. People altered their routines and local jurisdictions suggested, urged, or required changes meant to slow the disease’s spread.

By the end of June, however, public health officials and news outlets were talking about a second wave. In July, many states were pausing or reversing their plans to reopen while, for the second time, hospital systems worried about running out of room.

What could we have done better?

In an “editor’s pick” paper published today in the journal Chaos of the American Institute of Physics, Washington University in St. Louis researchers in the lab of Rajan Chakrabarty, associate professor in the department of Energy, Environmental and Chemical Engineering at the McKelvey School of Engineering, modeled the interplay between the duration and intensity of social distancing. They found a law of diminishing returns, showing that longer periods of social distancing are not always more successful when it comes to slowing the spread, and that any strategy that involves social distancing requires other steps be taken in tandem.

“Conventional wisdom was, the more intense and long-term the social distancing, the more you will curb the disease spread,” Chakrabarty said

“But that is true if you have social distancing implemented with contact tracing, isolation and testing. Without those, you will give rise to a second wave.”

Added Payton Beeler, a second year doctoral student in Chakrabarty’s lab, who also worked with Pai Liu, a postdoctoral fellow: “What we have found is that if social distancing is the only measure taken, it must be implemented extremely carefully in order for its benefits to be fully realized.”

Their susceptible, exposed, infected, and recovered (SEIR) dynamics model used data gathered by Johns Hopkins University between March 18 and March 29, a period marked by a rapid surge in COVID-19 cases and the onset of social distancing in most US states. Calibrating their model using these datasets allowed the authors to analyze unbiased results that had not yet been affected by large-scale distancing in place.

Unique to this project was the use of age stratification; the model included details on how much people of different age groups interact, and how that affects the spread of transmission.

No matter what strategy they looked at, one thing was clear, Chakrabarty said: “Had social distancing been implemented earlier, we probably would’ve done a better job.”

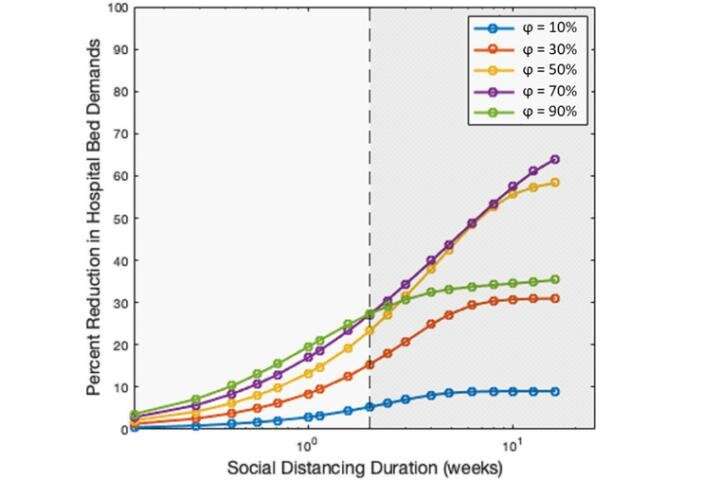

Researchers found that, over the short-term, more distancing and less hospital demand go hand in hand—but only up to two weeks. After that, time spent distancing does not benefit hospital demand as much; society would have to increase social distancing time exponentially in order to see a linear decrease in hospital demand.

Thus the diminishing return: Society would see smaller and smaller benefits to hospital demand the longer it spent social distancing.

If social distancing “alone” is to be implemented longer than two weeks, a moderate shut down, say between 50-70%, could be more effective for the society than a stricter complete shut-down in yielding the largest reduction in medical demands.

Another strategy for flattening the curve involves acting intermittently, alternating between strict social distancing and no distancing to alleviate the strain on hospitals—as well as some of the other strains on the economy and well-being imposed by longer-term distancing.

According to the model, the most efficient distancing- to- no-distancing ratio is 5 to 1; one day of no distancing for every five days at home. Had society acted in this way, hospital burden could have been reduced by 80%, Chakrabarty said. Exceeding this ratio, the model showed a diminishing return.

Critically, the researchers note that social distancing policy as a whole-of-government approach could not be successful without the implementation of wide-spread testing, contact tracing, and isolation of those found to be infected.

“And you have to do it aggressively,” Chakrabarty said. “If you do not, what you’re going to do, the moment you lift social distancing, is give rise to a second wave.”

That’s because the people who are leaving their homes after distancing themselves are, ostensibly, all susceptible to COVID-19.

“Bending the curve using social distancing alone is analogous to slowing down the front of a raging wildfire without extinguishing the glowing embers,” said Chakrabarty, whose other line of research focuses on the impacts of wildfires on climate and health.

“They are waiting to start their own fires once the wind carries them away.”

The model cannot inform strategies going forward because it used data collected in March, before any large-scale social distancing was implemented. But Chakrabarty said it may be able to inform our actions if we find ourselves in a similar situation in the future.

“Next time, we must act faster, and be more aggressive when it comes to contact tracing and testing and isolation,” Chakrabarty said. “Or else this work was for nothing.”

Brandie Jefferson, Washington University in St. Louis