Pancreatic islet transplants, which revive insulin production to treat type 1 diabetes, only last an average of three years.

By learning from a groundbreaking cancer treatment strategy based on a recent Nobel Prize-winning discovery, researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology and University of Missouri developed a new microgel drug delivery method that could extend the effectiveness of pancreatic islet transplantations—from several years to possibly the entire lifespan of a recipient.

Working across multidisciplinary teams using an animal model, the labs of Professors Andrés García at Georgia Tech and Haval Shirwan at the University of Missouri have developed a new biomaterial microgel that could deliver safer, smaller, and more cost-effective dosages of an immune-suppressing protein that could lead to better long-term acceptance of islet transplantations within the body.

The study was published August 28, 2020, in the journal Science Advances. The research was led by Maria Coronel, a postdoctoral fellow in the lab of García, the Parker H. Petit Chair and executive director of the Petit Institute for Bioengineering and Bioscience. García is also a Regents Professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering.

In 2018, the Nobel Prize for medicine was awarded for discovering how cancer cells send molecular signals to suppress immune response, thus hiding and protecting those cancer cells from the body’s immune system. Researchers soon developed pioneering treatment methods to signal and “turn on” the immune system (such as T cells) so the invading cancer would once again be recognized, allowing a patient’s own immune system to more effectively eliminate their cancer cells.

“The work we are doing is taking a page from that discovery and using immunotherapy in the opposite sense used by cancer treatments to control and ‘turn off’ an immune response to transplant a graft,” Coronel said. “When you get a transplant, like an islet transplant or organ transplant, even if it’s matched, you will have an immune response to that graft, and your immune system will recognize it as non-self and will try to reject and attack the site of the graft.”

After islet transplant surgery, traditional postoperative treatments use immune-suppressing systemic drugs that affect the entire body, and can be toxic—creating numerous, unwelcome side effects, whose severity often limits the number of candidates for islet and other organ transplants.

“A unique aspect of our method is that we have greatly reduced the dosage needed, which will significantly reduce or eliminate side effects currently caused by today’s systemic drug treatments,” said Coronel.

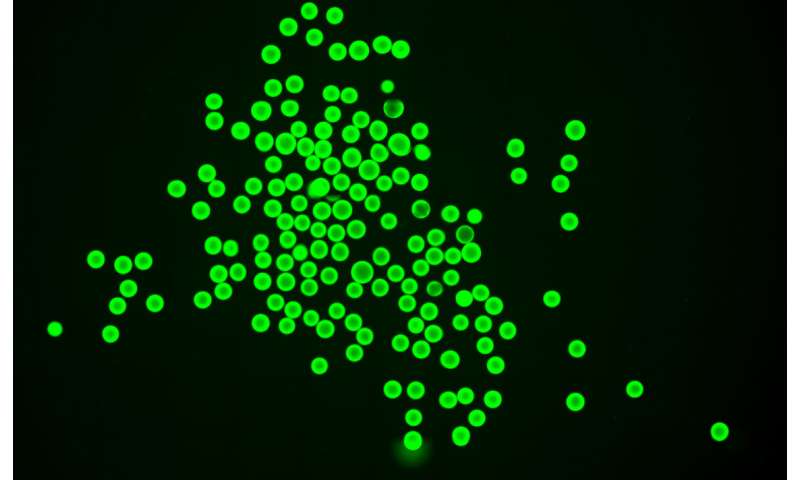

The research team developed a new “immune-acceptance” method, which inserts an engineered biomaterial—in this case a microgel—with the islets at the time of the transplantation. The microgels, which resemble clusters of micro-sized fish eggs, held and delivered a protein (SA-PD-L1) to a specific transplant area that successfully signaled the immune system to hold back an immune response, protecting a transplanted islet graft from being rejected. This locally delivered molecular signal, using SA-PD-L1, was designed to quietly suppress any immune response and was effective for up to 100 days with no additional systemic immune-suppressing drug intervention.

“We wanted to use PD-L1 for the prevention of allogeneic islet graft rejection by simulating the way tumor cells use this molecule to evade the immune system, but without resorting to gene therapy,” said Shirwan, professor of child health and molecular microbiology and immunology at the University of Missouri School of Medicine.

To achieve this goal, Shirwan worked with Esma Yolcu, professor of child health, also at the University of Missouri School of Medicine. Both were previously at the University of Louisville, where they generated the SA-PD-L1, a novel form of the molecule that can be positionally displayed on the surface of islet grafts or microgels for delivery to the graft site.

“Microgels presenting SA-PD-L1 represent an important technological development that has potential not only for the treatment of type 1 diabetes, but also other autoimmune diseases and various transplant types,” Shirwan said.

In addition to engineering this specific biomaterial microgel, the team tested its lifespan durability and dosage release possibilities. They also looked at its longer-term effects on both the graft and the immune response and function of the recipient—evaluating its long-term biocompatibility potential.

“One of the major goals in the diabetes field over the past two decades has been to allow the immune-acceptance of grafts and avoid the toxic drugs used to induce immune suppression, which affect the entire body,” García said.

“Generally speaking, organ transplantation is very successful at dealing with a variety of chronic conditions. These are very exciting results as proof of principle that demonstrate this engineered biomaterial and procedure may provide a platform technology that is applicable to other transplantation settings and may enlarge the pool of candidates who can safely receive transplants.”

Walter Rich, Georgia Institute of Technology