In the condition known as cavernoma, lesions arise in a cluster of blood vessels in the brain, spinal cord or retina. Researchers from Uppsala University can now show, at molecular level, that these changes originate in vein cells. This new knowledge of the condition creates potential for developing better therapies for patients. The study has been published in the journal eLife.

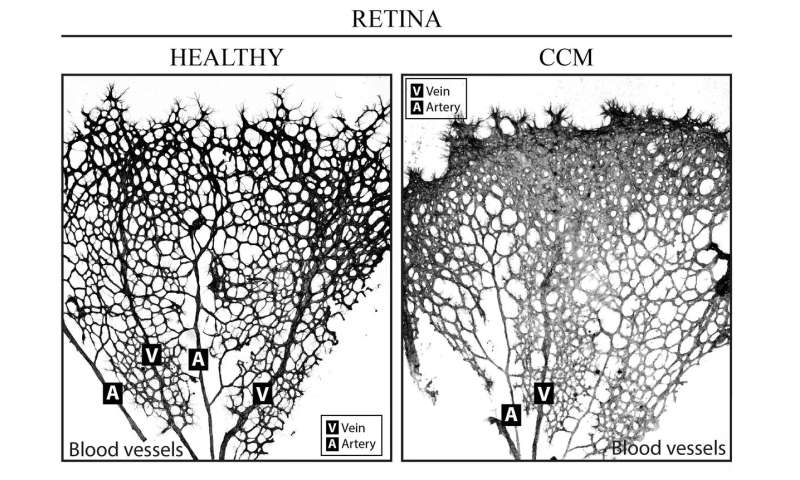

The vascular lesions, or blood-vessel malformations, that appear in a cerebral cavernoma—also known as a cerebral cavernous malformation (CCM) or, in the US, cavernous angioma—resemble mulberries. They bleed easily, which may cause epileptic attack, neurological problems and stroke. The condition is due to genetic mutations that may be inherited or occur spontaneously, and is incurable at present. Surgery is an option but, in patients with the hereditary form in whom new CCMs arise constantly, only a temporary solution.

How, and in which kind of blood vessel, the mutations occur has not been entirely clarified to date. In the present study, the researchers at Uppsala University—in collaboration with IFOM, the FIRC Institute of Molecular Oncology, and the Mario Negri Institute of Pharmacological Research in Italy—investigated endothelial cells. The function of these cells, which line the interior of blood vessels, varies according to vessel type, contributing to the differing features of arteries, veins and capillaries. In all, the scientists have analyzed more than 30,000 individual endothelial cells in detail to identify how, and in which vessels, CCMs appear.

“One of the genes that may mutate in the inherited form of CCM is called CCM3. We’ve examined mouse brain endothelial cells, after specific endothelial deletion of CCM3. The cells were clustered in venous and arterial endothelial cells, and we were able to see that venous endothelial cells were particularly sensitive to loss of the CCM3 gene,” says Peetra Magnusson of the Department of Immunology, Genetics and Pathology (IGP).

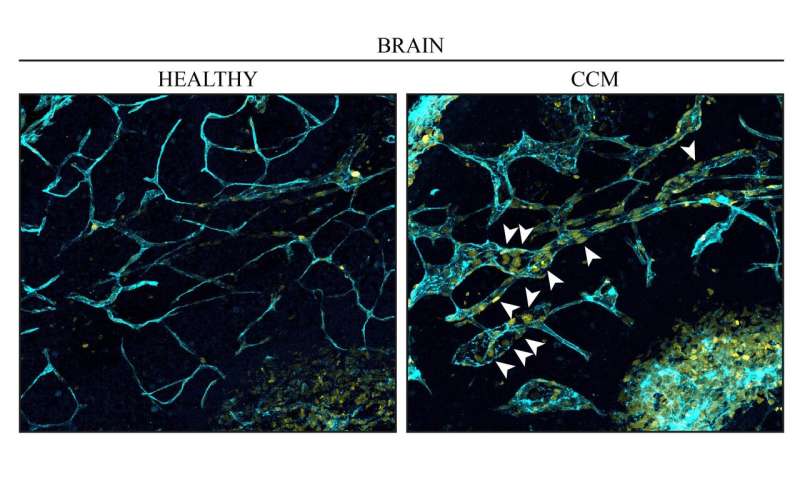

When CCM3 was lacking in mural endothelial cells of the venous type, the researchers observed increased cell division and abnormal growth of the vessels, leading to the characteristic mulberry-like lesions. The study thus confirms, at molecular level, that the vascular malformations of a cavernoma arise in veins. This had been seen previously only when the structure of the blood vessels had been studied in vessel fragments.

“Another interesting result from the study was that arterial endothelial cells were not affected at all in the same way by losing their CCM3. Although the CCM3 gene was also missing in these cells, they don’t contribute to development of the malformations,” says Elisabetta Dejana, who led the study.

“Summing up, our findings have brought new knowledge about cavernoma, which should improve the chances of developing improved clinical treatments.”

Uppsala University