Researchers provide the first physiological evidence that a foundational center of the brain influences how sound is processed, identify a previously unknown neural circuit

For the first time, researchers have provided physiological evidence that a pervasive neuromodulation system – a group of neurons that regulate the functioning of more specialized neurons – strongly influences sound processing in an important auditory region of the brain. The neuromodulator, acetylcholine, may even help the main auditory brain circuitry distinguish speech from noise.

“While the phenomenon of these modulators’ influence has been studied at the level of the neocortex, where the brain’s most complex computations occur, it has rarely been studied at the more fundamental levels of the brain,” says R. Michael Burger, professor of neuroscience at Lehigh University.

Burger and Lehigh Ph.D. student Chao Zhang?along with collaborators Nichole Beebe and Brett Schofield of Northeast Ohio Medical University and Michael Pecka of Ludwig-Maximilians University Munich?conducted the research. The findings have been described in an article, “Endogenous Cholinergic Signaling Modulates Sound-evoked Responses of the Medial Nucleus of the Trapezoid Body,” published earlier this month in The Journal of Neuroscience. The journal’s editors designated the article as “noteworthy” and it was included in “featured research” for its particular significance to the scientific community.

“This study will likely bring new attention in the field to the ways in which circuits like this, widely considered a ‘simple’ one, are in fact highly complex and subject to modulatory influence like higher regions of the brain,” says Burger.

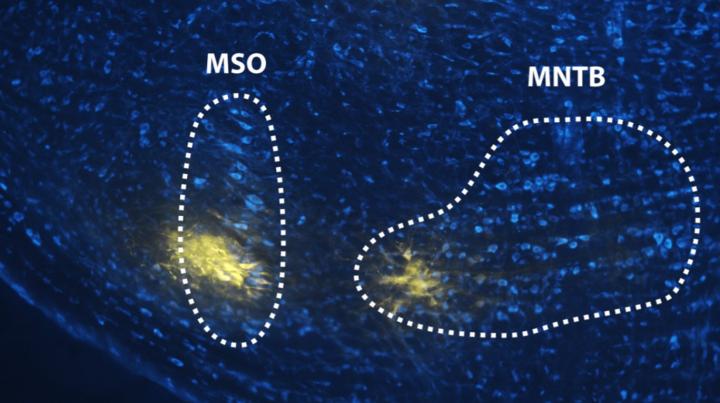

The team conducted electrophysiological experiments and data analysis to demonstrate that the input of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, a pervasive neuromodulator in the brain, influences the encoding of acoustic information by the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB), the most prominent source of inhibition to several key nuclei in the lower auditory system. MNTB neurons have previously been considered computationally simple, driven by a single large excitatory synapse and influenced by local inhibitory inputs. The team demonstrates that in addition to these inputs, acetylcholine modulation enhances neural discrimination of tones from noise stimuli, which may contribute to processing important acoustic signals such as speech. Additionally, they describe novel anatomical projections that provide acetylcholine input to the MNTB.

Burger studies the circuit of neurons that are “wired together” in order to carry out the specialized function of computing the locations from which sounds emanate in space. He describes neuromodulators as broader, less specific circuits that overlay the more highly-specialized ones.

“This modulation appears to help these neurons detect faint signals in noise,” says Burger. “You can think of this modulation as akin to shifting an antenna’s position to eliminate static for your favorite radio station.”

“In this paper, we show that modulatory circuits have a profound effect on neurons in the sound localization circuitry, at very low foundational level of the auditory system,” adds Zhang.

In addition, during the course of this study, the researchers identified for the first time a set of completely unknown connections in the brain between the modulatory centers and this important area of the auditory system.

Burger and Zhang think these findings could shed new light on the contribution of neuromodulation to fundamental computational processes in auditory brainstem circuitry, and that it also has implications for understanding how other sensory information is processed in the brain.

LEHIGH UNIVERSITY