Through small, neighborhood classes, researchers at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh and Promundo-US significantly reduced sexual violence among teenage boys living in areas of concentrated disadvantage.

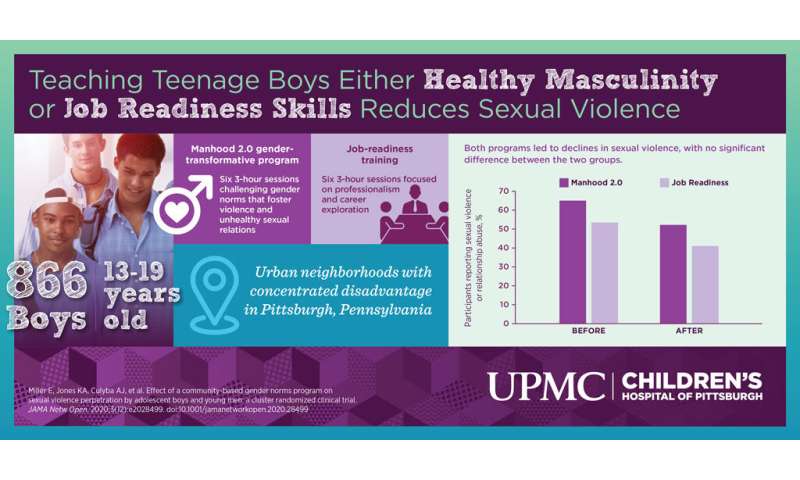

The study, published today in JAMA, is the culmination of a large Centers for Disease Control and Prevention clinical trial spanning 20 racially segregated neighborhoods in the Pittsburgh area to evaluate two violence prevention programs. The proportion of youth reporting the use of sexual or partner violence in their relationships decreased in both groups by about 12 percentage points.

“To accomplish something like this requires nurturing community partnerships,” said study senior author Elizabeth Miller, M.D., Ph.D., chief of adolescent and young adult medicine at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. “In each of these neighborhoods, we worked with community members to facilitate the programs with an eye toward sustainability.”

Between 2015-2017, nearly 900 boys between the ages of 13-19 enrolled in these small group programs, which were run by community leaders from each neighborhood.

Half of the sites were randomized to receive job readiness training and the other half were assigned a curriculum called “Manhood 2.0,” which is based on Promundo’s “Program H” in Brazil. The “H” stands for hombres.

“Manhood 2.0 engages young men in questioning harmful ideas about manhood,” said Promundo-US Chief Executive Officer Gary Barker. “It calls men into being part of the solution to ending violence in intimate partner relationships and helps them see the benefits to healthier manhood in their own lives.”

Manhood 2.0 was adapted for young men in U.S. urban communities, but the core message remains the same: challenging gender norms that foster violence against women and unhealthy sexual relationships.

For young men enrolled in Manhood 2.0, the use of partner violence—including physical or verbal abuse, sexual harassment, sexual coercion and cyber abuse—dropped from 64% at baseline to 52% in the months following the program. For those who received job training, self-reported sexual violence dropped from 53% to 41%.

That was a surprise. Miller said she expected job training to have a positive impact in other areas of life, but not violence towards women.

“Job skills training is a structural intervention, grounded in economic justice,” Miller said. “Perhaps this resonated and resulted in young men using less violence because they felt more hopeful about their future.”

Next, the researchers hope to study whether combining Manhood 2.0 with job readiness training might have an even greater impact on intimate partner and sexual violence than either curriculum alone.

“We know that young men often need job skills and opportunities to discuss healthy relationships and healthier manhood,” Barker said. “Combining these two proven approaches seems particularly promising and necessary.”

University of Pittsburgh