Cedar fever season is almost upon us, and at a time when having a fever—or even catching a slight cold—is concerning, it’s more important than ever to understand the symptoms and source of this common Central Texas allergy.

For starters, cedar fever isn’t a flu or a virus—it’s an allergic reaction to the pollen released by mountain cedar trees. In Texas, the predominant species of mountain cedar is the Ashe juniper.

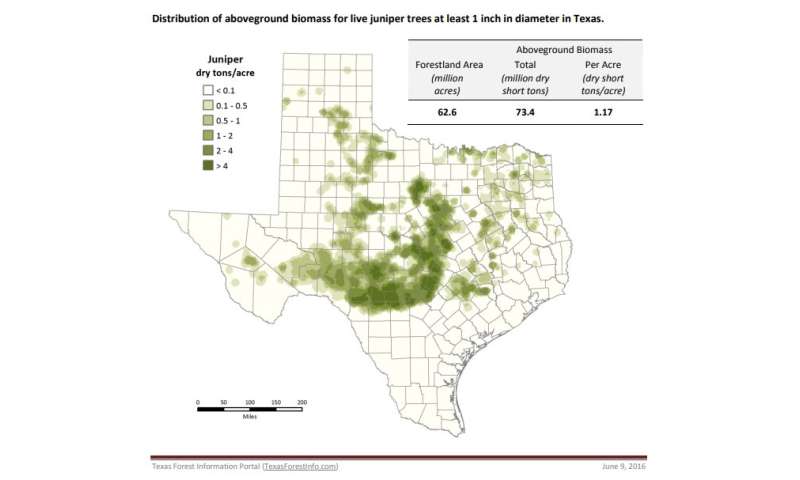

“Cedar fever is the worst west of I-35, where you have primarily juniper mixed in with oaks and some other species,” said Jonathan Motsinger, the Central Texas Operations department head for the Texas A&M Forest Service. “And because all of those junipers are producing pollen at the same time, you’re going to get a higher concentration of pollen in the air.”

This is one of the primary factors contributing to cedar fever—the sheer quantity and density of Ashe junipers in Central Texas. According to Robert Edmonson, a biologist for the Texas A&M Forest Service, the pollen from Ashe junipers isn’t particularly allergenic or harmful—it’s just so concentrated that, even if you aren’t generally susceptible to allergies, it could still affect you.

“There’s just so much pollen in the air,” said Edmonson, “it absolutely overwhelms the immune system. It’s like trying to breathe in a dust storm.”

Cedar or juniper, the response is the same

Since that pollen is wind disseminated, cedar fever can affect individuals far removed from areas with a high-concentration of juniper trees. And the source isn’t limited to Ashe junipers. In more eastern parts of the state, there are also eastern red cedars that pollinate around the same time—between December and January—and they can induce a similar response from people’s auto-immune systems.

Besides the sheer quantity of pollen released, cedar fever is mostly problematic because of when that pollen is released. Most trees pollinate in the spring, when we’re expecting to have allergies. Ragweed pollen and mold spores can contribute to allergies in the fall, but very few plants pollinate during the winter. Cedar trees are the exception—they are triggered by colder weather—and in Texas, their favorite time to release pollen is right after a cold front.

“Following a cold front,” said Edmonson, “the air dries out, we get some wind, and the pressure is different. Under those conditions, every single pollen cone on a juniper tree will open at one time, and it looks like the trees are on fire. It looks like there’s smoke coming off of them.”

While this creates for some fascinating imagery, it can also lead to some serious misery. And for people new to the Central Texas region, or unfamiliar with cedar fever as a whole, it can lead to genuine confusion since the pollination period of mountain cedar trees is also in the middle of flu season.

Symptoms in an already ‘watchful’ environment

It’s not uncommon for people experiencing cedar fever to mistake their symptoms as a cold or the seasonal flu, especially given the variety of symptoms triggered by cedar fever. According to Healthline’s article on cedar fever, these may include fatigue, sore throat, runny nose, partial loss of smell and—believe it or not—some people actually do run a fever.

This year could be particularly problematic, since many symptoms align with the novel coronavirus. But there are a few tell-tales to look out for. First of all, cedar pollen will rarely cause your body temperature to surpass 101.5. If your fever exceeds that temperature, then pollen likely isn’t the cause.

There are also a few symptoms of cedar fever that aren’t linked to the coronavirus, like itchy, watery eyes, blocked nasal passages and sneezing. But there is one “dead giveaway” that, according to Edmonson, should always clear things up. “If your mucus is running clear,” he said, “then it’s an allergy. If it’s got color, then it’s probably a cold or the flu.”

You can treat cedar fever by taking allergy medications and antihistamines, but you should consult with your physician or health care professional before taking new medications.

You can also try and anticipate the pollen by tuning in to your local news station, many of which will give you the pollen count and can predict when it’s going to be particularly bad. On those days, it’s smart to keep windows and doors closed, to limit the amount of time you spend outdoors, and to change air conditioning filters in your car and in your home.

Removing cedar trees from your property isn’t recommended primarily because the pollen is airborne and—since they often wait to release their pollen until it’s cold, dry and windy—that pollen can blow for miles. It’s also important to note that only male juniper trees release pollen.

“The male trees have pollen cones,” said Motsinger, “and the female trees have berry-like cones, which are very inconspicuous, but that’s what’s pollenated from the male trees.”

Finding good traits among the pollen fog

While junipers are notorious for releasing their fever-inducing allergens, they also have immense health benefits. Their berries, for instance, are used to make medicines and oils that can treat a variety of ailments, from an upset stomach to a snake bite. They are also high in nutrition and vitamins, providing a sustainable source of food for wildlife and soil enrichment.

Furthermore, they grow in a terrain that isn’t particularly hospitable to other species of tree. Most importantly, however, they provide the same mental, physical and environmental health benefits as trees and forests everywhere.

Ultimately, mountain cedars are really only singled out for the unusual time of year in which they pollinate.

“There are plenty of trees that produce copious amounts of airborne pollen,” explained Edmonson. “Coniferous trees do it, and oak trees can be just as bad in the spring. You get this light dusting of green everywhere, and that’s all pollen.”

Texas A&M University