The human brain contains approximately 86 billion neurons, or nerve cells, woven together by an estimated 100 trillion connections, or synapses. Each cell has a role that helps us to move muscles, process our environment, form memories, and much more.

Given the huge number of neurons and connections, there is still much we don’t know about how neurons work together to give rise to thought or behavior.

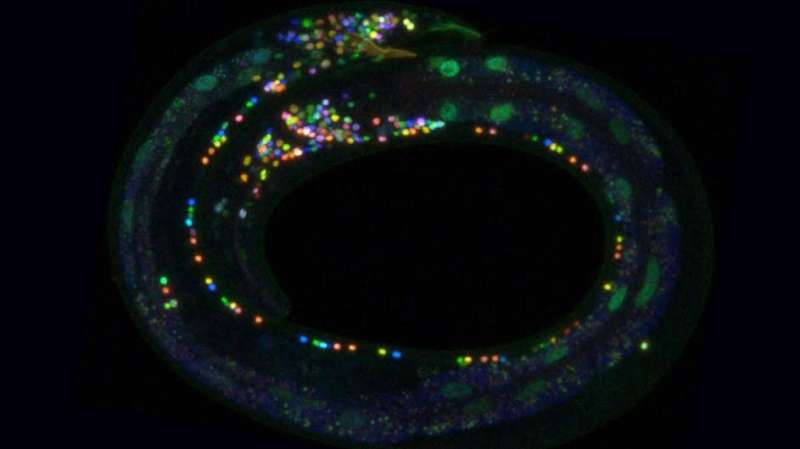

Now Columbia scientists have engineered a coloring technique, known as NeuroPAL (a Neuronal Polychromatic Atlas of Landmarks), which makes it possible—at least in experiments with Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans), a worm species commonly used in biological research—to identify every single neuron in the mind of a worm.

Their research appears in the Jan. 7 issue of the journal Cell.

NeuroPAL, which uses genetic methods to “paint” neurons with fluorescent colors, permits, for the first time ever, scientists to identify each neuron in an animal’s nervous system, all while recording a whole nervous system in action.

“It’s amazing to ‘watch’ a nervous system in its entirety and see what it does,” said Oliver Hobert, professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at Columbia and a principal investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. “The images created are stunning— brilliant spots of color appear in the worm’s body like Christmas lights on a dark night.”

To conduct their research, the scientists created two software programs: one that identifies all the neurons in colorful NeuroPAL worm images and a second that takes the NeuroPAL method beyond the worm by designing optimal coloring for potential methods of identification of any cell type or tissue in any organism that permits genetic manipulations.

“We used NeuroPAL to record brainwide activity patterns in the worm and decode the nervous system at work,” said Eviatar Yemini, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Biological Sciences at Columbia and lead author of the study.

Because the colors are painted into the neuron’s DNA and linked to specific genes, the colors can also be used to reveal whether these specific genes are present or absent from a cell.

The researchers said that the novelty of the technique may soon be overshadowed by the discoveries it makes possible. In advance of their Cell publication, Hobert and Yemini released NeuroPAL to the scientific community, and several studies already have been published showing the utility of the tool.

Being able to identify neurons, or other types of cells, using color can help scientists visually understand the role of each part of a biological system,” Yemeni said. “That means when something goes wrong with the system, it may help pinpoint where the breakdown occurred.”

Collaborators on the study include Liam Paninski, Columbia University; Vivek Venkatachalam, Northeastern University; and Aravinthan Samuel, Harvard University.

Carla Cantor, Columbia University