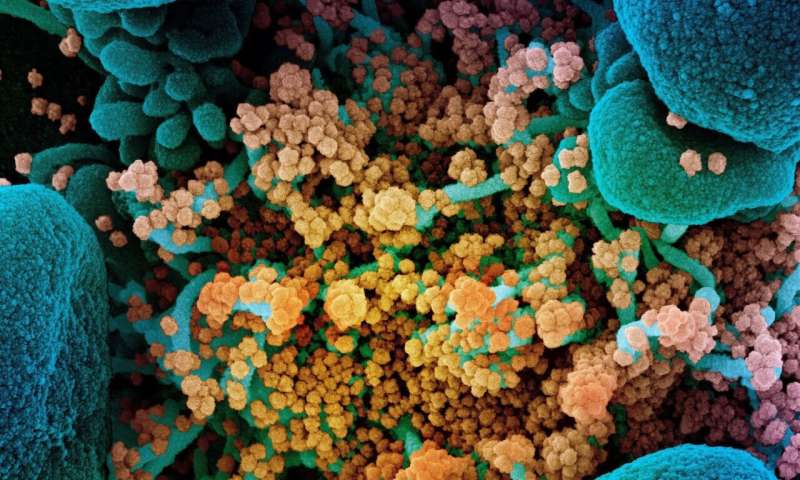

Seeking to understand why COVID-19 is able to suppress the body’s immune response, new research from the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology suggests that mitochondria are one of the first lines of defense against COVID-19 and identifies key differences in how SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, affects mitochondrial genes when compared to other viruses. These differences offer possible explanations as to why older adults and people with metabolic disfunction have more severe responses to COVID-19 than other individuals and they also provide a starting point for more targeted approaches that may help identify therapeutics, says senior author Pinchas Cohen, professor of gerontology, medicine and biological sciences and dean of the USC Leonard Davis School.

“If you already have mitochondrial and metabolic dysfunction, then you may, as a result, have a poor first line of defense against COVID-19. Future work should consider mitochondrial biology as a primary intervention target for SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses,” he said.

The study, published in the Nature journal Scientific Reports, expands on recent findings that COVID-19 mutes the body’s innate inflammatory response and reports that it does so by diverting mitochondrial genes from their normal function.

“We already knew that our immune response was not mounting a successful defense to COVID-19, but we didn’t know why,” said lead author Brendan Miller, a senior doctoral student at the USC Leonard Davis School. “What we did differently was look at how the virus specifically targets mitochondria, a cellular organelle that is a crucial part of the body’s innate immune system and energy production.”

Making use of the vast amounts of public data being uploaded in the early days of the virus outbreak, the research team performed RNA sequencing analyses that compared mitochondrial-COVID interactions to those of other viruses: respiratory syncytial virus, seasonal influenza A virus, and human parainfluenza virus 3. These reanalyses identified three ways in which COVID-19, but not the other viruses, mutes the body’s cellular protective response.

Chief among their findings is that SARS-CoV-2 uniquely reduces the levels of a group of mitochondrial proteins, known as Complex One, that are encoded by nuclear DNA. It is possible that this effect “quiets” the cell’s metabolic output and reactive oxygen species generation, that when functioning correctly, produces an inflammatory response that can kill a virus, they say.

“COVID-19 is reprogramming the cell to not make these Complex One-related proteins. That could be one way the virus continues to propagate,” says Miller, who notes that this, along with the study’s other observations, still needs to be validated in future experiments.

The study also revealed that SARS-CoV-2 does not change the levels of the messenger protein, MAVS mRNA, that usually tells the cell a viral attack has happened. Normally, when this protein gets activated it functions as an alarm system, warning the cell to self-destruct so that the virus cannot replicate, says Miller.

In addition, the researchers found that genes encoded by the mitochondria were not being turned on or off by SARS-CoV-2—a process that is believed to produce energy that can help the cell evade a virus—at rates to be expected when confronted with a virus.

“This study adds to a growing body of research on mitochondrial-COVID interactions and presents tissue and cell-specific effects that should be carefully considered in future experiments,” said Cohen.

University of Southern California