A diet rich in healthy and plant-based foods is linked with the presence and abundance of certain gut microbes that are also associated with a lower risk of developing conditions such as obesity, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, according to recent results from a large-scale international study that was co-senior authored by Andrew T. Chan, MD, MPH, from Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). The report appears in Nature Medicine.

“This study demonstrates a clear association between specific microbial species in the gut, certain foods, and risk of some common diseases,” says Chan, a gastroenterologist, chief of the Clinical and Translational Epidemiology Unit at MGH, and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. “We hope to be able to use this information to help people avoid serious health problems by changing their diet to personalize their gut microbiome.”

The PREDICT 1 (Personalized Responses to Dietary Composition Trial 1) metagenomic study analyzed detailed data on the composition of participants’ microbiomes, their dietary habits, and cardiometabolic blood biomarkers. The researchers found strong evidence that the microbiome is linked with specific foods and diets, and that, in turn, its composition is also associated with levels of metabolic biomarkers of disease. Further, the microbiome has a greater association with these markers than other factors, such as genetics.

“Studying the interrelationship between the microbiome, diet and disease involves a lot of variables because peoples’ diets tend to be personalized and may change quite a bit over time,” explains Chan. “Two of the strengths of this trial are the number of participants and the detailed information we collected.”

PREDICT 1 is an international collaboration to study links between diet, the microbiome, and biomarkers of cardiometabolic health. The researchers gathered microbiome sequence data, detailed long-term dietary information, and results of hundreds of cardiometabolic blood markers from just over 1,100 participants in the U.K. and the U.S.

The researchers found that participants who ate a diet rich in healthy, plant-based foods were more likely to have high levels of specific gut microbes. The makeup of participants’ gut microbiomes was strongly associated with specific nutrients, foods, food groups and general dietary indices (overall diet composition). The researchers also found robust microbiome-based biomarkers of obesity as well as markers for cardiovascular disease and impaired glucose tolerance.

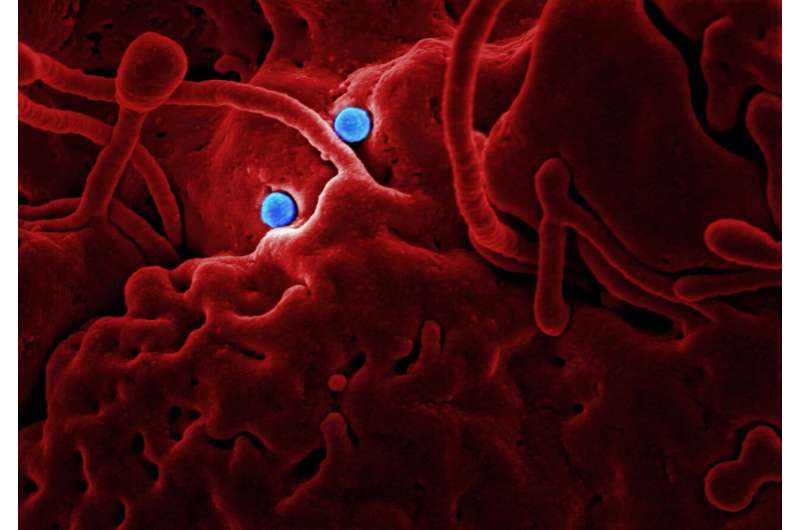

Epidemiologist Tim Spector of King’s College London, who started the PREDICT study, says: “When you eat, you’re not just nourishing your body, you’re feeding the trillions of microbes that live inside your gut.”

For example, having a microbiome rich in Prevotella copri and Blastocystis species was associated with maintaining a favorable blood sugar level after a meal. Other species were linked to lower post-meal levels of blood fats and markers of inflammation. The trends they found were so consistent, the researchers believe that their microbiome data can be used to determine the risk of cardiometabolic disease among people who do not yet have symptoms, and possibly to prescribe a personalized diet designed specifically to improve someone’s health.

“We were surprised to see such large, clear groups of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ microbes emerging from our analysis,” says Nicola Segata, Ph.D., professor and principal investigator of the Computational Metagenomics Lab at the University of Trento, Italy and coordinator of the analysis of the microbiome data in the study. “And it is intriguing to see that microbiologists know so little about many of these microbes that they are not even named yet.”

Curtis Huttenhower, Ph.D., a co-senior author who co-directs the Harvard T.H. Chan Microbiome in Public Health Center, adds: “Both diet and the gut microbiome are highly personalized. PREDICT is one of the first studies to begin unraveling this complex molecular web at scale.”

Francesco Asnicar, Ph.D., and Sarah Berry, Ph.D., are co-first authors of the study. Other collaborators were from health science company ZOE, which supported the research.

Massachusetts General Hospital