Nurses have been putting themselves in harm’s way every day since the pandemic began. But as coronavirus spreads rapidly in the UK, it has become clear that those in intensive care units are now under more pressure than others.

Hospitals are nearing capacity in many parts of the country, and in some regions temporary mortuaries have been set up as hospital morgues begin to overflow.

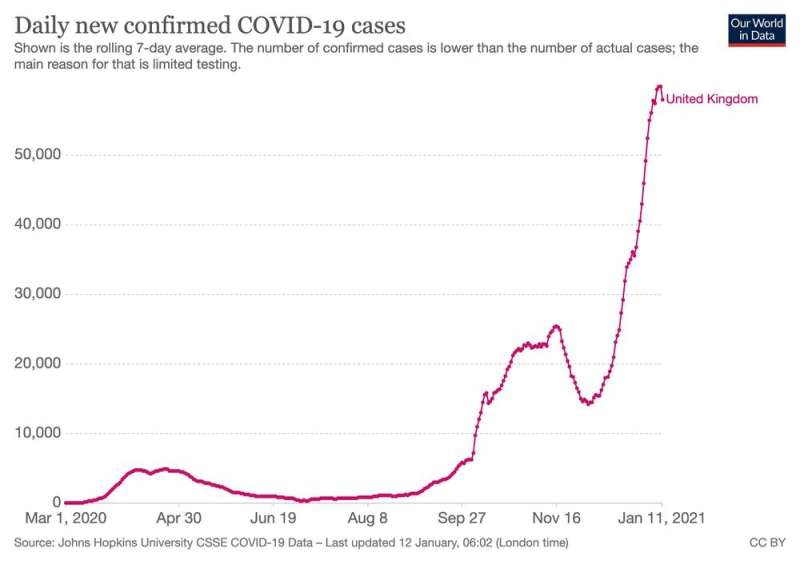

At the end of 2020, a leaked email revealed that the Royal London Hospital was operating in “disaster-medicine mode” and unable to provide high-standard critical care. Cases have only risen since then.

This situation has been brewing for a while. When the pandemic struck the UK, the National Health Service in England was already short of 40,000 nurses due to lacking government investment, inadequate workforce planning and the ongoing mass exit of nurses from the profession.

Now, on top of these pre-existing workforce issues and high rates of infection, hospitalization and deaths, nurses are also grappling with widespread staff sickness due to COVID-19.

Pressure on intensive care

The recognition of how highly skilled and essential nurses truly are has only now begun to dawn on some people, including healthcare leaders.

Working in an ICU requires a unique skill set, which makes it difficult to fully staff the units when they are so busy. Some non-specialists have been re-deployed to critical care from other areas, but all these staff need special training and supervision, causing further stress for the already overstretched ICU nurses.

The standard ratio for ICUs is usually one nurse per critically ill patient. But in response to the pandemic, guidelines have changed so that one nurse can be expected to care for up to four patients depending on the nature of their illness.

This means at any one time, there may not be enough people on hand to safely turn patients in bed, resulting in joint pain and back injury.

The physical strain of wearing PPE for long shifts, which among other things prevents nurses from being able to drink or eat, only adds to the burden for staff.

Psychological trauma

Nursing as a profession has developed models and theories to underpin care, which help maintain standards and ensure that nurses are able to offer emotional support and comfort to those they care for.

Witnessing people dying without the support of loved ones is particularly emotionally stressful and directly challenges nurse’s professional standards of care.

Being forced to make constant, impossible choices about priorities is heart-breaking for nurses. Many have spoken out about how the high rate of COVID deaths, which sometimes results in multiple patients losing their lives within one shift, is deeply traumatic for staff. Some have described working in an ICU as being like stepping into a war zone. It’s no surprise, then, that a new study has found that 40% of ICU staff in England are suffering from symptoms consistent with PTSD.

Feelings of not being able to control what is happening to them or those they care for can result in toxic workplace stress which has a measurable negative impact on health and wellbeing. The mental health of nurses working under this pressure is already deteriorating and can result in long-term psychological damage.

Hard work for little reward

We should not forget that nursing is not a well-paid job, with many nurses earning below the median salary for the UK.

Low pay is the most common reason cited by nurses for wanting to leave the profession. There seems little doubt that the combination of the pandemic with stress, declining standards and low pay will lead to further departures.

Speaking out about these challenges is not easy for nurses—the NHS in England is currently under a level 4 national incident which means all official communication to the public and the media is supposed to be controlled centrally. This leaves many to suffer in silence.

Throughout the pandemic, nurses and other essential workers have been described as “heroes”. The Clap for Our Carers movement from the UK’s first lockdown, designed to help the public give public thanks to frontline pandemic workers, has been brought back for 2021 under the new title, Clap for Heroes.

But nurses are not heroes. They are technically expert professional carers with unique skills. Clapping is a poor substitute for allowing them the freedom to speak up about the concerns they may have about their own health and wellbeing and those they care for.

Ann Hemingway, The Conversation