Cancer is a notoriously complex disease, in part because it may be caused by mutations among hundreds or even thousands of genes. In addition, most cancers exhibit an extraordinary amount of variation among genetic mutations, even between patients with the same types of cancers.

Consequently, cancer researchers have chosen to study interactions among groups of genes in certain biological pathways that are disrupted.

When genes in certain pathways are frequently mutated or disrupted, that pathway may play a critical role in the initiation or development of cancer. But unraveling the molecular mechanisms underlying those disruptions is extremely complex.

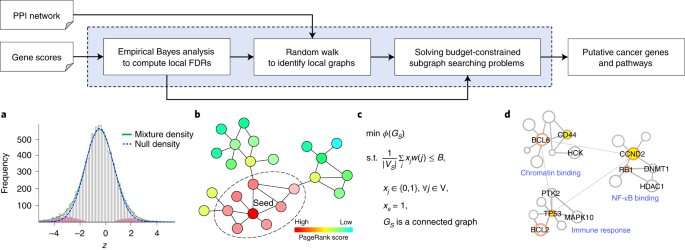

Now, University at Buffalo researchers have developed a new, statistically more powerful method called FDRnet that can more effectively detect key functional pathways in cancer using genomics data generated by next-generation sequencing technology.

Published in Nature Computational Science on Jan. 14, the new method has the potential to give biologists more precise data with which to zero in on therapeutic targets.

“Using the new method, we can find biological pathways in which genes are significantly mutated or disrupted,” explained Yijun Sun, Ph.D., associate professor of bioinformatics in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology in the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at UB and the corresponding author. “It addresses some key challenges in molecular pathway analysis in cancer studies. Once the tumor biologists obtain this information, they can use it to verify our findings, and from there develop new cancer treatments,” he said.

“By overcoming the limitations of existing approaches, FDRnet can facilitate the detection of key functional pathways in cancer and other genetic diseases,” said Sun.

When Sun and his co-authors tested FDRnet on simulation data and on breast cancer and B-cell lymphoma data, they found that FDRnet was able to detect which subnetworks or pathways are significantly perturbed in these cancers, potentially leading tumor biologists to identify new therapeutic targets.

Ellen Goldbaum, University at Buffalo