Oxygen deficit, also called hypoxia, in the brain is actually an absolute state of emergency and can permanently damage nerve cells. Nevertheless, there is growing evidence that to a certain extent, hypoxia can also be an important signal for growth. Together with scientists from the University Hospitals of Copenhagen and Hamburg-Eppendorf, researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Experimental Medicine in Göttingen have shown in mice that mentally and physically demanding activity triggers not only a local but also a brain-wide “functional hypoxia.” Although in an attenuated form, the effects are similar to oxygen deprivation. The shortage of oxygen activates, among other things, the growth factor erythropoietin (Epo), which stimulates the formation of new synapses and nerve cells. This mechanism could explain why physical and mental training have a positive effect on mental performance into old age.

Last year, researchers at the Max Planck Institute in Göttingen found out in experiments in animal studies with mice that mentally and physically demanding activities trigger a slight oxygen deficit in certain brain regions. This ultimately leads to the formation of new nerve cells. They observed that hypoxia activates the growth factor erythropoietin (Epo) in the brain. Although it is known primarily for its stimulating effect on red blood cells, Epo also promotes the formation of nerve cells and their networking in the brain.

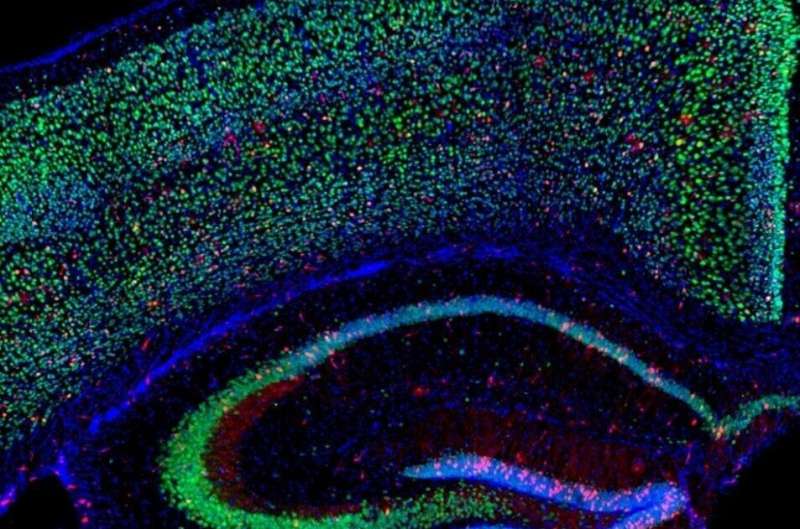

In a new study, the research group examined in detail which brain regions and cell types are affected by the shortage of oxygen. To do this, they used genetically modified mice that produce a molecule throughout the brain that leads to the formation of a fluorescent dye when there is an oxygen deficit. In order to challenge the mice both mentally and physically, the researchers let them run on specially prepared running wheels for several days. The mice had to concentrate while running on these wheels to avoid stumbling in addition to being physically exerted. Mice that had no access to a running wheel and mice exposed to oxygen-depleted air served as comparator groups. The researchers also examined the activation of genes in different brain regions and cell populations in order to find out how the brain reacts to activity-induced hypoxia.

Change in gene activity

In fact, running wheel training had effects similar to reducing the oxygen content in the air we breathe. In both cases, the change in the activity of many genes was similar, and a mild oxygen deficit occurred throughout the brain. However, there were major differences between different cell types: nerve cells were particularly affected, whereas the glial cells (auxiliary cells of the neurons) were only slightly affected. In addition, the Epo gene in the brain, together with a number of other genes, is particularly stimulated during both mental and physical activity.

“We still don’t know whether mild hypoxia as a result of activity also leads to stronger networking of nerve cells—and even to their formation—in humans. We therefore want to carry out similar studies on humans—for example on test subjects who are active on exercise bikes,” says Hannelore Ehrenreich, head of the study. The findings could ultimately benefit patients with neurodegenerative diseases in which nerve cells die or lose synapses.

Max Planck Society