A team of researchers has found disrupting the interaction between cancer cells and certain immune cells is more effective at killing cancer cells than current immunotherapy treatments.

The findings, which include studies in cell lines and animal models, appeared in JCI Insight and focus on a protein called CD6 as a target for a new approach to immunotherapy.

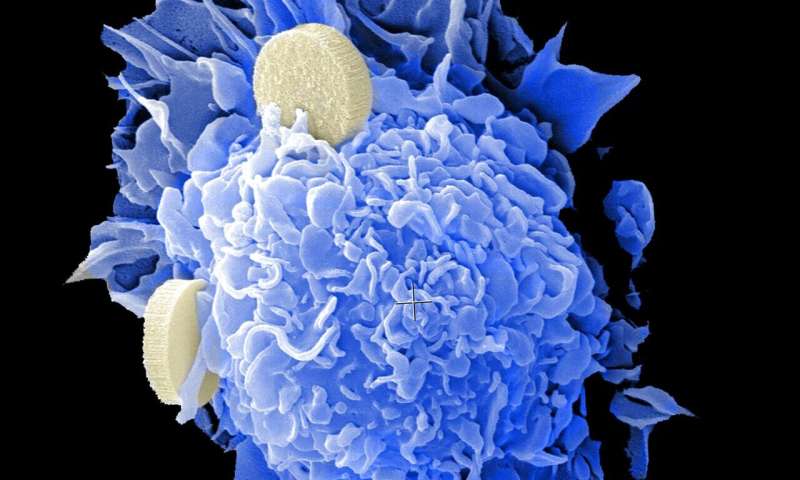

Over the past two decades, new approaches to cancer treatment have been developed that block immune checkpoints, which are receptors on the surface of certain immune cells, like natural killer T cells. Cancer exploits these immune cells and render them dormant.

This treatment, called checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy, gives these immune cells a chance to fight back. Unfortunately, though, patients that become cancer-free are often left with autoimmune conditions that, in some patients, can eventually be fatal.

Only approximately one third of patients with cancer ultimately benefit from currently available immune checkpoint inhibitors.

“I’m interested in how cancer cells interact with certain immune cells to control the immune response to cancer, and how the immune system interacts with organs and tissues to cause autoimmune diseases,” says study senior author David Fox, M.D., a rheumatologist and cancer researcher at the University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center. “How can researchers intervene to alter these interactions and simultaneously destroy cancers while preventing autoimmunity?”

Fox’s lab and collaborators at the Cleveland Clinic Research Foundation have been studying the roles of CD6 and receptors it interacts with as it related to autoimmunity for many years. Previously, the research team was able to create man-made CD6 and CD318, a receptor that CD6 interacts with, to act like human antibodies in the immune system and fight off cancer cells.

This new study proved successful in combatting human breast cancer, lung cancer and prostate cancer in cell lines, indicating that the anti-CD6 antibody, known as UMCD6, could be useful in treating a wide range of cancer types.

They also grafted human breast cancer cells into immunocompromised mice, and followed up with transferring human immune cells into the mice. When given an injection of UMCD6, the tumors almost completely disappeared in just one week, compared to mice treated without UMCD6.

The findings have implications beyond this first description of a potential new approach to against cancer. The ability of UMCD6 to prevent and treat autoimmune diseases makes the potential implications for cancer immunotherapy especially intriguing, the researchers say.

It’s been known that CD6 has to play a role in autoimmunity, since mice that don’t have CD6 on their immune cells have major suppression of autoimmune diseases.

Prior research has shown that an antibody that binds to CD6 and pulls it from the cell surface to the inside of the cell can effectively treat autoimmune mouse models of three different human diseases: rheumatoid arthritis, an inflammatory disease that causes the immune system to inflame the membrane that lines the joints, multiple sclerosis, a disease that affects the central nervous system, brain and spinal cord, and uveitis, an eye disease that can cause blindness.

Now, when treated with UMCD6, Fox saw the mice show striking reductions in disease activity, autoimmunity and organ damage in mice.

“When UMCD6 binds to CD6 on these specific immune cells, it creates a CD6 cluster that dives into the interior of the cell, allowing no CD6 to remain on the cell surface” says Fox. “This causes the killer T cells to seek out and destroy the cancer cells much more aggressively. At the same time, removing CD6 from the surface of CD4 cells, with the same UMCD6 antibody, controls and limits the activity of the CD4 cells, which are the cells that instigate autoimmune diseases.”

“Until now, we haven’t been able to get immune cells to kill cancer cells without triggering an immune response that can be harmful to patients,” he adds. “What we’ve created here completely challenges prevailing concepts.”

So how close are researchers to studying UMCD6 in humans?

There are ongoing studies of anti-CD6 antibodies in India, where an anti-CD6 antibody has been approved for the treatment of psoriasis. However, in the United States, substantial research remains to be done to translate the discovery from laboratory models to human clinical trials.

“If UMCD6 is proven to successfully treat cancer and prevent recurrences, this could overcome the major current limitations to checkpoint inhibition success in human cancer immunotherapy,” says Fox. “I look forward to seeing what lies ahead in this field of research.”

University of Michigan