A new study in laboratory rats has discovered a direct link between low oxygen in the womb and impaired memory function in the adult offspring. It also finds that anti-oxidant supplements during pregnancy may protect against this.

Low oxygen in the womb—known as chronic fetal hypoxia—is one of the most common complications in human pregnancy. It can be diagnosed when a routine ultrasound scan shows that the baby is not growing properly and is caused by a number of conditions including pre-eclampsia, infection of the placenta, gestational diabetes or maternal obesity.

The new results show that chronic fetal hypoxia leads to a reduced density of blood vessels, and a reduced number of nerve cells and their connections in parts of the offspring’s brain. When the offspring reaches adulthood, its ability to form lasting memories is reduced and there is evidence of accelerated brain ageing.

Vitamin C, an anti-oxidant, given to pregnant rats with chronic fetal hypoxia was shown to protect the future brain health of the offspring. The results are published today in the journal FASEB Journal.

“It’s hugely exciting to think we might be able to protect the brain health of an unborn child by a simple treatment that can be given to the mother during pregnancy,” said Professor Dino Giussani from the University of Cambridge’s Department of Physiology, Development and Neuroscience, who led the study.

The researchers used Vitamin C because it is a well-established and used anti-oxidant. However, only high doses were effective, which could cause adverse side-effects in humans. Follow-up studies are now searching for alternative anti-oxidants to treat chronic fetal hypoxia in humans.

To conduct the research, a group of pregnant rats were kept in ambient air with 13% oxygen—causing hypoxic pregnancies. The rest were kept in normal air (21% oxygen). Half of the rats in each group were given Vitamin C in their drinking water throughout the pregnancy. Following birth, the baby rats were raised to four months old, equivalent to early adulthood in humans, and then performed various tests to assess locomotion, anxiety, spatial learning and memory.

The study found that rats born from hypoxic pregnancies took longer to perform the memory task, and didn’t remember things as well. Rats born from hypoxic pregnancies in which mothers had been given Vitamin C throughout their pregnancy performed the memory task just as well as offspring from normal pregnancies.

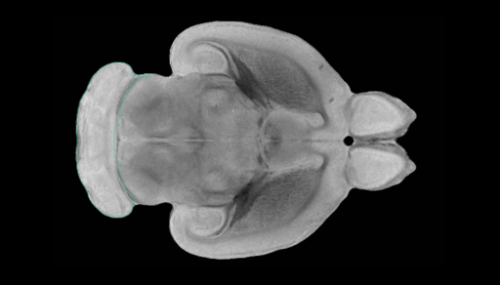

Analysing the brains of the rat offspring, the researchers found that the hippocampus—the area associated with forming memories—was less developed in rats from hypoxic pregnancies.

In deeper analysis, the scientists showed that hypoxic pregnancy causes excess production of reactive oxygen species, called ‘free radicals’, in the placenta. In healthy pregnancy the body keeps the level of free radicals in check by internal anti-oxidant enzymes, but excess free radicals overwhelm these natural defences and damage the placenta in a process called ‘oxidative stress’. This reduces blood flow and oxygen delivery to the developing baby.

In this study, placentas from the hypoxic pregnancies showed oxidative stress, while those from the hypoxic pregnancies supplemented with Vitamin C looked healthy.

Taken together, these results show that low oxygen in the womb during pregnancy causes oxidative stress in the placenta, affecting the brain development of the offspring and resulting in memory problems in later life.

“Chronic fetal hypoxia impairs oxygen delivery at critical periods of development of the baby’s central nervous system. This affects the number of nerve connections and cells made in the brain, which surfaces in adult life as problems with memory and an earlier cognitive decline,” said Dr. Emily Camm from Cambridge’s Department of Physiology, Development and Neuroscience, first author of the report, who has recently taken up a new position at The Ritchie Centre in Australia.

The interaction between our genes and lifestyle plays a role in determining our risk of disease as adults. There is also increasing evidence that the environment experienced during sensitive periods of fetal development directly influences our long-term health—a process known as ‘developmental programming.’

Brain health problems that may start in the womb due to complicated pregnancy range from attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, to brain changes in later life that have been linked with Alzheimer’s disease.

“In medicine today there has to be a shift in focus from treatment of the disease, when we can do comparatively little, to prevention, when we can do much more. This study shows that we can use preventative medicine even before birth to protect long term brain health,” said Giussani.

University of Cambridge