Researchers from Trinity College Dublin have discovered that some skeletal defects associated with a lack of movement in the womb during early development may still be ameliorated after such periods of immobility if movement resumes.

The researchers’ discovery was made using chicken embryos, which develop similarly to their human equivalents and which can be easily viewed as development takes place—raising hopes that the finding may also apply to humans and thus have important implications for therapeutic interventions.

The research has just been published in leading international journal, Disease Models and Mechanisms.

Why babies need to move in the womb

Fetal movement in the uterus is a normal part of a healthy pregnancy and previous research by the group has shown that key molecular interactions that guide the cells and tissues of the embryo to build a functionally robust yet malleable skeleton are stimulated by movement.

If an embryo doesn’t move, a vital signal may be lost or an inappropriate one delivered in error, which can lead to the development of brittle bones or abnormal joints. As such, reduced or absent movement can lead to problems with development of bones and joints including joint dysplasia and temporary brittle bone disease in infants.

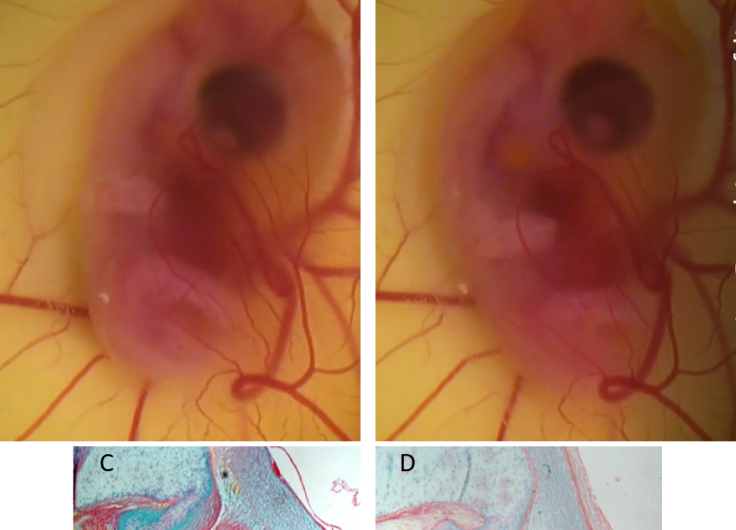

The researchers behind the current work have previously uncovered what precisely goes wrong at a cellular and molecular level when embryo movement is restricted, showing when and which bones and joints are affected

Play00:0000:11MuteSettingsPIPEnter fullscreen

The new findings

In the new study the researchers asked what happens if movement resumes after a defined period of movement restriction early in development. They specifically addressed whether joint and spine formation can recover.

Dr. Rebecca Rolfe, Research Fellow in Zoology, in Trinity’s School of Natural Sciences, is the first author of the journal article. She said:

“We compared resumption of normal movement to hyperactive movement and found that limb joints recover better than spinal defects and, among specific limb joints, those of the hips and knees recover best under the conditions tested.

“We also found that hyperactive movement led to greater improvement in joint development, especially at the hip, indicating that clinical conditions resulting from reduced activity of the fetus in the womb could be ameliorated with physical movement or manipulation even after an initial problem becomes apparent.”

Paula Murphy, Professor in Zoology in Trinity’s School of Natural Sciences, and senior author of the journal article, added:

“This work essentially demonstrates that movement post-paralysis can partially recover specific aspects of joint development, which we hope could inform therapeutic approaches to ameliorate the effects of human fetal immobility.

“Skeletal defects at birth can present significant hurdles for infants to overcome in trying to lead normal, healthy lives. Although this will not lead immediately to new therapeutic options it gives specific indications of the types of therapy that would be potentially beneficial.”

Trinity College Dublin