Two decades ago, Soumya Swaminathan watched her HIV-infected patients suffer often horrific and unnecessary deaths. There was a treatment for their disease, but they simply could not afford it.

The World Health Organization’s chief scientist told AFP the inequalities in accessing COVID-19 vaccines today hark back to the late 1990s, when she helplessly watched HIV patients in India wither away when drugs were saving lives in the West.

Effective treatments for HIV were first produced in the mid-1990s, but they carried a prohibitively high price tag of over $10,000 per patient per year.

It would take nearly a decade before they became available to poorer populations.

“I had patients that I was watching die… horrible prolonged deaths, when treatments were already available in the West,” Swaminathan said in a recent interview.

“I lost so many patients and children were orphaned. Those images still haunt me.”

‘Morally, ethically wrong’

The Indian paediatrician and clinical scientist, who today is one of the top WHO officials leading global efforts to coordinate the pandemic response, said it was disappointing that the world was repeating past mistakes.

“You have to learn from history, but we don’t seem to,” she said.

To date, only 0.3 percent of COVID vaccine doses have been administered in the world’s poorest countries, which are home to nearly 10 percent of the global population.

“That is very difficult to witness, and it is morally and ethically wrong,” Swaminathan said.

The glaring unevenness in vaccine access comes despite a concerted effort to address the historical inequities.

The WHO and others have created Covax, a global vaccine-sharing programme, but it remains severely underfunded and has faced significant supply shortages, delaying efforts to roll out vaccines in poorer countries.

Still, Swaminathan said she believed Covax was slowly making a difference and hoped it would eventually be “a success story.”

The persisting inequities have meanwhile been an added frustration as Swaminathan and her team have battled to understand COVID-19 and to provide the information needed to rein it in.

‘Extremely difficult’

The first months of the pandemic were “extremely difficult,” the 62-year-old acknowledged.

As the WHO’s chief scientist, she said she felt “an enormous sense of responsibility”.

In addition there is the personal strain for Swaminathan, who moved on her own to Geneva for the job, leaving behind her husband, grown children and the rest of her family in India, which is now in the grip of an explosive outbreak.

“At the back of your mind you’re worrying about family,” she said, adding she was particularly concerned for the wellbeing of her elderly parents.

Her father, the famous geneticist M. S. Swaminathan known for his role leading India’s Green Revolution, is 95, while her mother, renowned educationalist Mina Swaminathan, is 88.

Swaminathan, who usually starts her day before 7:00 am and works until late in the evening, said she had strived to “maintain a work-life balance” to avoid burn-out.

‘World not doing enough’

Long daily walks near her home on the outskirts of Geneva, through lush and pristine greenery, are part of her routine.

“Nature has been therapeutic for me,” she said.

That therapy has been welcome as her team worked tirelessly to keep up with and communicate the constantly-evolving science around COVID-19.

“We were building the ship and sailing it, as they say, and that is always stressful,” she said.

“There are days when you feel terribly depressed and sad and upset,” she admitted, “especially when you see the images of people impacted around the world, the healthcare workers who have died, my own colleagues and classmates whom I’ve lost.”

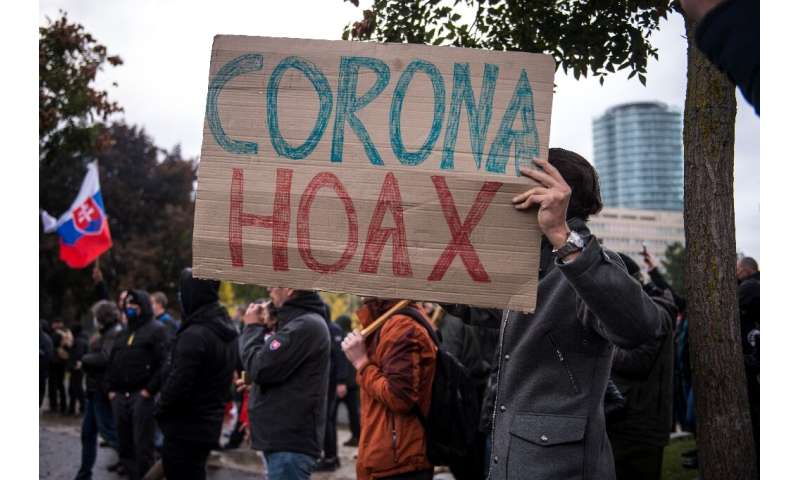

One of the biggest frustrations, Swaminathan said, has been constant pushback from a large “anti-science movement”.

“There are not only sceptics, but there are people who wilfully plant conspiracy theories,” she said.

She added that it has been tough fighting misinformation while striving to provide science-backed guidance on the virus and its spread.

“We haven’t always gotten it right the first time,” Swaminathan said. “Unfortunately, when you are dealing with a new virus and a new epidemic, you don’t know everything on day one.

“But that’s the way science evolves.”

As for what we have learned from the pandemic, Swaminathan said the biggest lesson is the need to ensure equal access to life-saving vaccines and drugs.

“We need to address this,” she said. “The world is clearly not doing enough.”

Nina Larson