Coronavirus-induced anxiety and depression continue to exert a mental toll on U.S. residents, especially among young adults, even as rising U.S. vaccination rates and falling COVID-19 cases signal a gradual return to pre-pandemic rhythms, according to a new survey by researchers from Northeastern, Harvard, Northwestern, and Rutgers.

Since the researchers began conducting regular surveys of U.S. residents about the COVID-19 pandemic in April 2020, respondents have indicated no improvement in the prevalence of sleepless nights, depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts.

About 28 percent of the 22,000 U.S. residents surveyed reported levels of depression that would typically require professional treatment. That was down slightly compared to the peak of 30 percent in December 2020 but remained about three times higher than before the pandemic, researchers found.

Twenty-three percent said they had considered suicide, about the same as in December.

Adults 18 to 24 years of age—typically college students and first-time parents—were hit hardest by the psychological fallout from lockdowns, social isolation, and online learning, with the most recent survey showing 42 percent of them reporting at least moderate depression. That figure was down from 47 percent in October, but still the highest among all age ranges.

Respondents 65 years and older were the least affected, with just 10 percent reporting that they felt depressed.

“Younger adults have lives that are more dynamic than older adults,” says David Lazer, university distinguished professor of political science and computer sciences at Northeastern and one of the researchers who conducted the study. “They’re finishing school, getting a job, starting a family, all things that are more likely to be disrupted by the pandemic.”

By a wide gap, elevated rates of depression were more prevalent in parents with children at home (35 percent) than those without children (25 percent). The stress of juggling their children’s remote education and the demands of their jobs were the likely reasons, Lazer said.

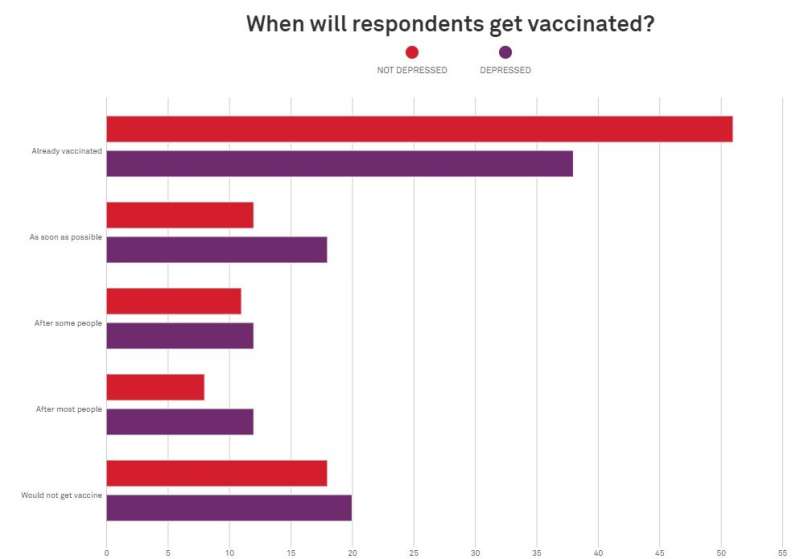

The survey found that 51 percent of respondents who say they are suffering from depression are people who have yet to be vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. Among those who have received a coronavirus vaccination, 32 percent reported symptoms of depression. People with depression are open to getting vaccinated but may encounter barriers to getting their shots, according to the survey.

“Because they’re depressed, they’re less able to translate their preferences [to get inoculated] into action,” Lazer suggests. “There’s definitely an association with being vaccinated and not being depressed.”

Asian Americans reported an increase in rates of depression (to 27 percent from 22 percent), Lazer said, likely triggered by a sharp rise in violent acts against Asian Americans during the pandemic. While the numbers of Asian Americans who report depression have generally been lower than any other racial or ethnic group, the responses of Asian Americans are now similar to all except Hispanic respondents, who consistently report the highest rates of depression at 33 percent.

President Joe Biden issued a proclamation marking April as National Mental Health Awareness Month that said nearly one in five Americans lives with a mental health condition. Even before COVID-19, the prevalence of mental health conditions was on the rise, with nearly 52 million adults experiencing some form of mental illness in 2019, the proclamation said.

“Youth mental health is also worsening, with nearly 10 percent of America’s youth reporting severe depression,” the president wrote. “We must treat this as the public health crisis that it is and reverse this trend.”

Northeastern’s Lazer says the survey was conducted between April 1 and May 3, more than a week before the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said that vaccinated people do not have to wear masks or maintain a distance from others indoors or outdoors, with some exceptions.

The CDC announcement may raise people’s spirits and repair some of the psychological damage caused by the pandemic. Lazer and his fellow researchers plan to gather further data in the summer, when people will be enjoying their first mask-free vacations in a long time.

“Ask me in six weeks, because we’re going to go back out there in June and then we’ll be able to see if people are a lot happier,” he says.

Peter Ramjug, Northeastern University