The emergence of variants of concern in late 2020 hearkened a shift in the COVID-19 pandemic as “variants” entered the public lexicon. The acceleration of the Delta variant around the world is raising questions about its origin, transmissibility, hotspots and potential for vaccine resistance.

What is a variant?

Through genome sequencing, we can determine specific orders of individual genes and the nucleotides that make up strands of DNA and RNA. If we think of the virus as a book, it’s as though all of the pages have been cut up into pieces. Sequencing allows us to determine all of the words and sentences in their proper order. Variants differ from one another based on mutations. So, two copies of the book would be “variants” if one or more of the cut-up pieces were different.

We should also appreciate that variants have been emerging throughout the pandemic with no effect on viral behaviors. However, the emergence of variants of concern, where mutations have resulted in altered virus characteristics (increased transmission and disease severity, reduced vaccine effectiveness, detection failure) have had deleterious health consequences.

Emergence and transmission of B.1.1.7 (Alpha), B.1.351 (Beta) and P.1 (Gamma) in Canada resulted in third waves of transmission leading to overwhelmed health-care systems and implementation of further restrictions. The World Health Organization introduced a new naming system, based on the Greek alphabet, for coronavirus variants in the spring 2021.

What is the Delta variant, where did it emerge?

The Delta variant is a variant of concern also known as B.1.167.2 and is one of three known sub-lineages of B.1.167. According to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Delta variant was first detected in India in December 2020.

What makes this variant different from other variants of concern?

One of the defining features of the Delta variant has been enhanced transmissibility with increases estimated at 40-60 percent above the Alpha variant. Recent data from Scotland suggested that the risk of hospitalization doubled following infection with Delta (compared to Alpha), especially in those with five or more other health conditions. Increased risk of hospitalization was observed from data in England.

Epidemiological analysis, which looks at things like the distribution of infection and the severity of illness, can often provide rapid assessments of changes to virus characteristics. Studying specific mutations using structure-activity relationship analysis, which looks at how the chemical structure of the virus affects its biological activity, can also provide clues, although validation is often time-consuming.

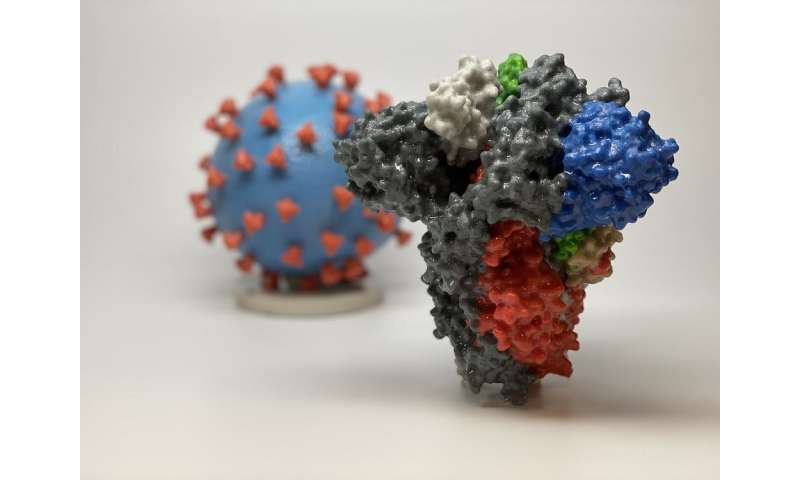

Early structure-activity relationship analyses have focused on the relation of three mutations to Delta’s behavior. Notably, a preprint study that has yet to be peer reviewed suggested that three mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein may make the variant more transmissible by making it easier for the spike protein to bind to the receptor in human cells (known as the ACE2 receptor).

If we return to the book analogy, that means that three of the cut-up pieces in the Delta version of the book are different from the original. Each of these three pieces may makes it easier for the virus to infect human cells.

What do we know about the epidemiology of the Delta variant and its hotspots?

Evidence suggests that Delta played a large role in the surge of COVID-19 cases observed in India in 2021. Since then, this variant has spread globally. As of June 14, the Delta variant has been detected in 74 countries, accounted for over 90 percent of new cases in the United Kingdom, and at least six percent of total cases in the U.S., with estimates as high as 10 percent.

Much of what we know about the Delta variant is derived from Public Health England. The Delta variant was first detected in the U.K. near the end of March 2021, and linked to travel. As of June 9, the number of confirmed or probable cases was 42,323, with wide and heterogenous distribution across the U.K.

In Canada, Delta was first detected in early April in British Columbia. Although Alpha is the most dominant variant lineage detected in Canada, Delta’s growth has accelerated across many provinces. Alberta data suggests that the number of cases is doubling every six to 12 days. Ontario has estimated that 40 percent of its new cases as of June 14, 2021 are due to Delta. Modeling results from B.C. suggest Delta will significantly contribute to overall trajectory by this August.

It is important to note that Delta’s reported prevalence is an underestimate because a timely screening test has not yet been developed.

What do we know about Delta and vaccines?

Early analysis from the U.K. about vaccine effectiveness against the Delta variant has provided some optimism.

Data from Scotland indicated that vaccination with either AstraZeneca or Pfizer reduced hospitalizations and infections, though less than for the Alpha variant. However, evidence suggests that two-dose immunizations with AstraZeneca or Pfizer reduced hospitalizations by 92 percent and 96 percent, respectively. Protection from symptomatic disease was reduced by 17 percent for Delta compared to Alpha with only a single dose of vaccine. Modest reductions in effectiveness against symptomatic disease were noted following two vaccine doses.

The spread of the Delta variant has made getting people vaccinated with two doses a major public health policy goal, and these results support that. However, first doses appear to provide substantial protection from severe illness requiring hospitalization.

Jason Kindrachuk and Souradet Shaw, The Conversation