At the height of her eating disorder Zhang Qinwen was the weight of a child. Her hair fell out, she was unable to walk and she could barely see.

“I knew that I was seriously unwell, but I did not dare go to the doctor,” the 23-year-old, now a leading campaigner in China on the issue, told AFP at a landmark exhibition in Shanghai.

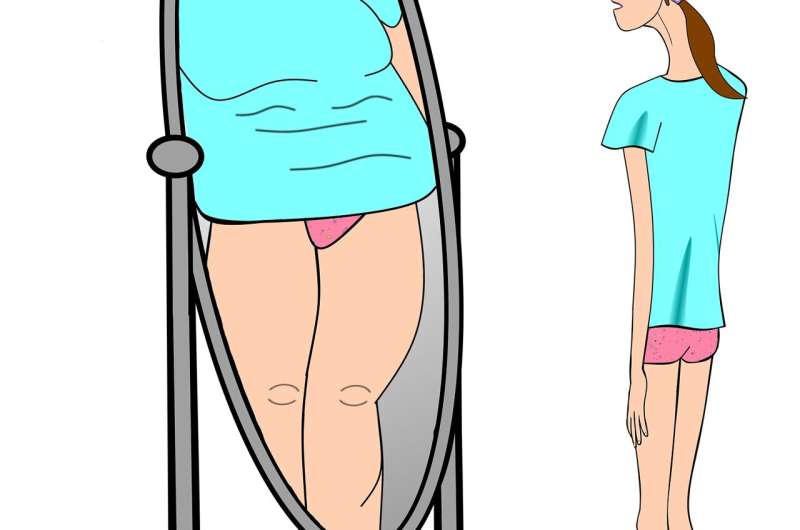

While disordered eating can affect anyone, western studies have indicated they are most prevalent in teenage girls and young women, and often those already impacted by other mental health problems.

“I was simply affected by the internet and had low self-esteem back then,” said Zhang, who weighed just 28 kilos (60 pounds) before ending up in intensive care.

“I thought I was not perfect enough.”

She is far from alone, but despite some Chinese hospitals warning of fast-rising cases, recognition in China is limited—as is the availability of treatment.

Zhang, who studied in Britain, said in comparison “in China, you may talk to many people, including counsellors and non-specialist clinics, and perhaps they don’t know what the disease is and how to help us”.

Her exhibition, which hopes to shine a light on the illness, has haunting paintings of a tearful school girl, displays of discarded medication and the word “KILL” projected on a whitewash wall.

‘Foreign phenomenon’

While there are no national statistics, hospitals in major Chinese cities have reported steep increases of people seeking treatment.

In Shanghai, a mental health clinic said it treated just three cases of eating disorders in 2002—but saw 591 people who identified as having similar issues in 2018.

Two years ago the state-run China Youth Daily, citing a Beijing hospital, said that from 2002 to 2012 the number of ED patients jumped from about 20 annually to more than 180.

In 2011 the hospital opened a specialist ward.

The increase in people recognising their disordered eating has led to suggestions the issue is a “foreign phenomenon” that only arrived in China recently.

“For my parents’ generation, when they were young, being fat was a way to prove that you came from good family background,” said 21-year-old student Xie Feitong at Zhang’s exhibition.

State broadcaster CGTN also linked eating disorders with the country’s growing wealth.

“As Chinese society starts to focus more on personal well-being and higher standards of living, more women are speaking out about their struggle with obsessing over weight loss and a flawless body image,” it said.

Like in other countries, social media in China can play a role in propagating what the ideal body should look like.

Viral posts online—often around challenges demonstrating how thin a person is—can encourage body-shaming and bullying, and tap into the dominant beauty ideal of pale skin and thin bodies.

Offline, pervasive beauty standards endure: earlier this month a gallery was forced to pull a photo exhibition that ranked women’s attractiveness after an outcry.

Strong hearts

Zhang’s exhibition responds to many of those harmful stereotypes, with female participants taking part in a performance—parodying marriage—to celebrate and accept their bodies.

Her story of extreme weight loss, mental torture and reluctance to seek help was echoed by several young women at the show.

Others described being bullied at school for not being thin enough, white enough or pretty enough.

Most rejected the notion that eating disorders were “new” to China—although all agree that it is only in the last one or two years that the issue has been publicised.

Xie believes that Chinese women have been emboldened by the global #MeToo movement to challenge traditional ideas of what constitutes beauty in China.

“I am dark and fat—the opposite of white, young and thin,” said Xie, who battled anorexia from the age of 13 and was hospitalised.

“But in the process of my recovery, I feel that a healthy skin tone, a sturdy body and a strong heart are the most important thing in this world.”

Zhang, a wedding veil on her head, added: “We always felt that our bodies had many defects.

“At this ‘wedding’ we want to say that we are truly in love with ourselves.”