For women diagnosed with breast cancer in Florida, breast cancer-specific mortality rates have decreased more among Black and Hispanic women than white women since 1990, according to results of a study published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

“Over the past three decades, we’ve seen an improvement in breast cancer survival for all women—especially for minority women—which is encouraging,” said lead author of the study Robert Hines, Ph.D., MPH, associate professor of population health sciences at the University of Central Florida College of Medicine. “However, in the most recent time period, non-Hispanic Black women have twice the rate of breast cancer death compared to non-Hispanic white women.”

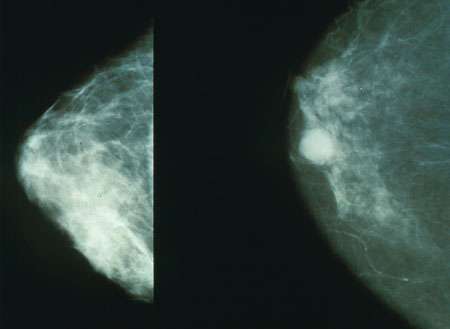

Around 1990, breast cancer mortality rates began to decline, reflecting improved screening and the availability of new therapeutics, but the decline was far slower in Black women, Hines explained.

“Since the 80s, there’s been increasing awareness of the disparities in breast cancer mortality and the troubling fact that they’ve grown over time,” Hines said. “There’s been a huge investment in decreasing or eliminating these disparities, but we wanted to see if it’s been effective.” Such initiatives have largely focused on improving screening education and availability for socioeconomically disadvantaged populations and racial and ethnic minorities.

Hines and colleagues obtained records from the Florida Cancer Data System of over 250,000 women diagnosed with breast cancer from the years 1990-2015. Their sample set consisted of female patients who self-identified as non-Hispanic white (79.5 percent), non-Hispanic Black (10.5 percent), Hispanic white (9.7 percent), or Hispanic Black (0.3 percent). The researchers studied the cumulative incidence of breast cancer death as well as 5- and 10-year relative hazard rates for individuals in each group. They clustered patients based on year of diagnosis: 1990-1994, 1995-2004, and 2005-2015.

On a national level, over the past several decades the incidence of breast cancer diagnosis in Black women has been less than that for white women, and Black women have been more likely to be diagnosed with more advanced disease. Over time, incidence in Black women rose to nearly the same level as that of white women, an effect Hines attributes to targeted breast cancer surveillance in those populations.

“The percentage of non-Hispanic Black women aged 50-74 who have had mammograms in the past two years is higher than for non-Hispanic white women in the most recent data for Florida,” Hines said. “Clearly the message has gotten out.”

Researchers also found that for all racial and ethnic groups, mortality decreased gradually from 1990 to 2015. In non-Hispanic white women, 10-year mortality decreased from 20.6 percent in the first five years (1990-1994) to 14.0 percent in the final time period (2010-2015). In non-Hispanic Black women, 10-year mortality decreased from 36.0 percent to 25.9 percent.

In the most recent 10 years surveyed, there was no significant difference in five- or 10-year mortality rates between Hispanic white and non-Hispanic white women, data that Hines found both surprising and encouraging. But despite these advances, Hines stresses that Black women still have double the five- and 10-year mortality rates of non-Hispanic white women.

“We need to celebrate the progress we make,” Hines said. “But we have a ways to go to produce equitable outcomes for women diagnosed with breast cancer.”

As next steps, Hines and his team hope to identify specific factors underlying the continuing disparities, in order to advise future initiatives aimed at closing the gap. The results of the current study hinted at possible directions. When the researchers normalized the mortality data based on age, insurance status, census-tract poverty, tumor stage and grade at diagnosis, and treatment received, the 10-year relative rate of breast cancer mortality for Black women—which was 102 percent higher than white women prior to normalization of data—decreased to 20 percent higher than white women.

“These factors, as a group, explained a lot of the disparity, but in order to have the most impact, we need to tease out the individual factors that are most responsible,” Hines said.

Limitations of this study include incomplete data for a fraction of patients, especially at earlier time points, when some of the diagnostic criteria used often today were not commonly assessed. The study also excluded patients who identified as a race other than white or Black, or an ethnicity other than Hispanic.

American Association for Cancer Research