The virus that gives rise to COVID-19 is the third coronavirus to threaten humanity in the past two decades. It also happens to move more efficiently from person to person than either SARS or MERS did. The first African case of COVID-19 was diagnosed in Egypt in mid-February of 2020. Four weeks later, the first lockdowns began across Africa. Steven Schiff, Brush Chair Professor of Engineering at Penn State, who already had established research partnerships in Uganda, saw an opportunity for his team to apply what they were learning from their ongoing efforts to track and control infectious disease and provide countries such as Uganda with more information to help guide policy to mitigate the viral pandemic.

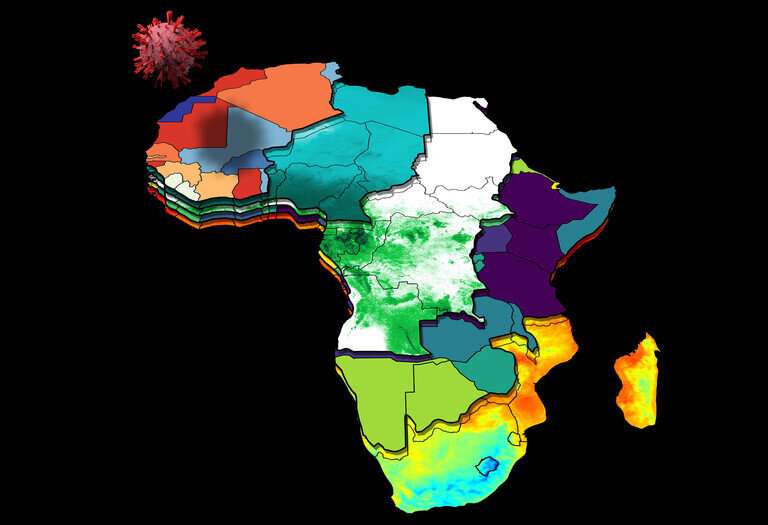

The result was a multi-country collaboration to develop a surveillance modeling tool that provides a weekly projection of expected COVID-19 cases in all African countries, based on current case data, population, economic status, current mitigation efforts and meteorological sensing from satellites. Developed in collaboration with Uganda’s National Planning Authority (NPA), the country’s senior organization for development and economic planning, the tool’s COVID-19 projections use openly available data to provide a projection of cases, as well as lower and upper ranges to help the country decide if mitigation policies need to be implemented or modified.

The researchers published their approach on June 29 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. The project was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health Director’s Transformative Research Award, a grant awarded to Schiff in 2018 for his “high-risk, high-reward” approach to predictive, personalized public health (P3H).

Prediction guiding prevention in the face of a pandemic

“When the COVID-19 pandemic began, we had this unusual team of scientists hard at work on implementing P3H in Africa, and we thought that we had much we could contribute toward the fight against this new virus,” said Schiff, who founded the Penn State Center for Neural Engineering and serves as a professor of engineering science and mechanics in the College of Engineering and of neurosurgery in the College of Medicine.

The team includes Paddy Ssentongo, assistant research professor of engineering science and mechanics. Ssentongo is originally from Uganda, where he earned a medical degree before moving to Penn State to complete a master of public health and a doctorate in epidemiology. He graduated this year.

“This pandemic has shown us that we need to put more emphasis on global public health—especially in places with fragile health care systems, including many countries in Africa,” Ssentongo said. “If we wait for people to get sick, we’re already losing. The best thing we can do is prevention.”

The researchers reached across disciplines to bring in experts—from epidemiologists to meteorologists to economists—on every factor influencing viral spread.

“We pulled together a large team to tackle what was necessary,” said Schiff, who is also a researcher in the Penn State Neuroscience Institute. “The team consists of 19 people across four countries, plus many more individuals who contributed through discussions and support.”

The complexity of mitigation

Equally important as understanding the number and location of people with active cases, according to Schiff, is understanding the importance of weather, geography and other factors, especially in developing countries where many people live and work in more exposed conditions than do people in industrialized countries.

“If a coastal country closes its borders, landlocked Uganda is likely going to see cases go up because they depend on the coastal countries for imports—without the imports, people will move around and interact more to find work and food,” Schiff said, noting that such changes in movement may create shifts in projections of new cases from neighboring countries versus internal cases. “You need information gathered in real-time on the virus, such as testing and lockdowns, as well as the other influencing factors such as the varied economic security of different countries and their health systems. Our strategy synthesizes all of these data across Africa to make surprisingly good projections of the expected number of cases based on how these factors interact and influence COVID transmission in the population.”

Abraham J. B. Muwanguzi, paper co-author and manager of the science and technology department at the NPA, also serves as the principal investigator in Uganda on Schiff’s NIH grant.

“We’re working closely with the Ministry of Health to use the model in analyzing how the COVID trends are moving,” Muwanguzi said. “In September and October of 2020, at the peak of COVID cases, the model projected an increase in cross-border cases, prompting the government to close our border. We had fewer cases than projected because we were able to mitigate a predicted source that was captured well in the model.”

Muwanguzi also noted that the tool not only helps provide data for mitigation policies, but it also helps the country plan how to use its resources.

“For example, in March and April of this year, the model projected a tremendous drop in cases,” Muwanguzi said. “Our hospital centers started emptying out—there really were fewer cases. We could then scale down operations and reappropriate resources to other areas of need.”

Yet, on June 18, Uganda entered a 42-day lockdown after the daily number of new cases increased from fewer than a hundred at the end of May to nearly 2,000. The week after the lockdown started, the model projected 11,222 new cases would be reported if no mitigation efforts were put in place.

“Unlike the previous wave where factors influencing the spread were mostly from outside the country, the current wave is influenced by internal factors,” said Joseph Muvawala, executive director of NPA, in a column published by New Vision, a national newspaper in Uganda. “With these statistics, a total lockdown was inevitable, irrespective of the known economic consequences; human life is far too precious to lose.”

According to Muvawala’s column, the projected increases have helped Uganda better prepare their hospital centers by procuring enough supplies and planning to avoid overwhelming hospitals and health care workers.

However, Ssentongo warned, the model is only as good as the data provided to it.

“We hope other countries in Africa will not only use this tool, but also collaborate to make sure they are integrating data in terms of testing and reporting cases,” Ssentongo said. “The tool is a roadmap to tell a country how the pandemic is evolving and where the country is going. It’s successful if the country sees the projections, implements mitigation efforts and sees a lower number of actual cases.”

Global benefit of global collaboration

According to Schiff, their findings clearly demonstrate the advantages of inter-country cooperation in pandemic control.

“This is a crisis that no single country can fully manage on its own,” Schiff said.

The researchers plan to continue updating the tool with more information as it becomes available, as well as implement data regarding vaccinations as they become more available in Africa. It is available freely online.

“One of the limitations of doing science is that you can do clever work, publish in a good journal that is reviewed by your peers, but it is still difficult to translate the work into effective policy,” Schiff said. “We wanted to implement this tool to do good and help save lives. We could never have accomplished this without the close collaboration with our African colleagues in Uganda. It was critical to make sure this was a framework that people who make policy can use and apply in their work—that’s what makes this valuable.”

Ashley J. Wennersherron, Pennsylvania State University