A “perfect storm” of genetic mutations, toxic proteins and a defect in natural cell recycling has been uncovered in University of Queensland research that could lead to treatments for neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

Researchers have found brain cells are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of the triple threat, and two genes—PINK-1 and PDR-1—are likely to contribute significantly to that vulnerability.

Research leader Dr. Steven Zuryn from UQ’s Queensland Brain Institute said these genes could be potential therapeutic targets for treating Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

“The research has opened up some interesting new links that could help us to better understand brain disorders and could be exploited to mitigate cell damage,”‘ Dr. Zuryn said.

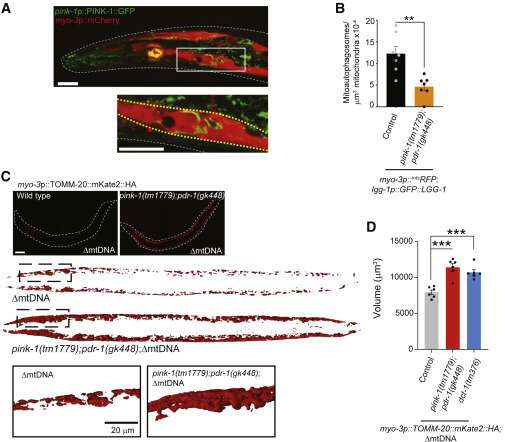

The team studied a natural process called mitophagy, which acts to target damaged mitochondria for recycling.

Mitochondria are embedded in our cells and help supply energy as well as aid cell signaling, growth and natural death.

Mitochondria also have their own DNA—mtDNA—that can develop genetic mutations.

“We found evidence that defects in PINK-1 and PDR-1, which can cause early-onset Parkinson’s disease, can drive these mutations to higher levels in brain cells,”‘ Dr. Zuryn said.

“The presence of toxic and disease-associated proteins, including tau, in the cells can also increase mutation levels, because they can block the activity of PDR-1.

“The discoveries suggest that two hallmarks of virtually all neurodegenerative disease—mitochondrial dysfunction and the effects of toxic or disease-associated proteins—converge at the mitochondrial DNA.”‘

mtDNA mutations can be passed from mother to child, and an accumulation of the mutations may contribute to the progressive nature of late-onset Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

Dr. Zuryn’s research suggests this process is exacerbated by defects in the PINK-1 and PDR-1 genes and by the presence of toxic proteins.

“Our laboratory is now uncovering ways in which to prevent the inheritance of mtDNA mutations and develop means to counteract their damaging effect—whether they are inherited or develop during the normal course of life,”‘ he said.

“We believe that this will ultimately lead to treatments against devastating mitochondrial diseases and a range of neurodegenerative diseases.”‘

The research has been published in Cell Reports.

Erik de Wit, University of Queensland