A specific police action, an arrest or a shooting, has an immediate and direct effect on the individuals involved, but how far and wide do the reverberations of that action spread through the community? What are the health consequences for a specific, though not necessarily geographically defined, population?

The authors of a new UW-led study looking into these questions write that because law enforcement directly interacts with a large number of people, “policing may be a conspicuous yet not-well understood driver of population health.”

Understanding how law enforcement impacts the mental, physical, social and structural health and wellbeing of a community is a complex challenge, involving many academic and research disciplines such as criminology, sociology, psychology, public health and research into social justice, the environment, economics and history.

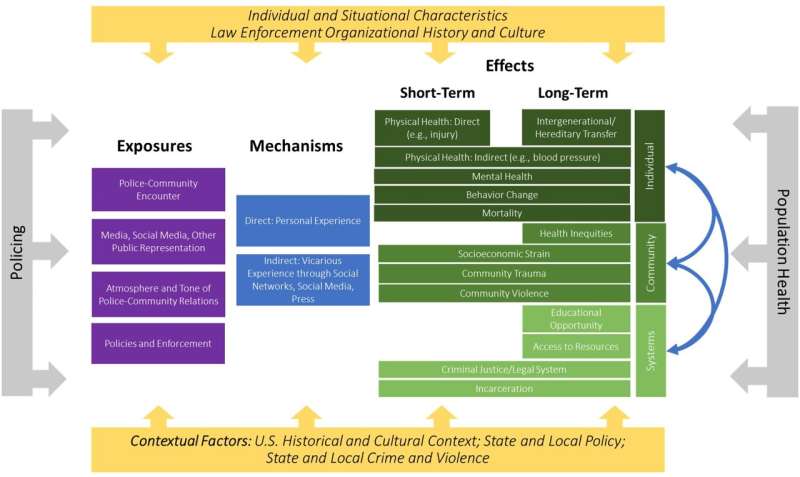

“We needed a map for how to think about the complex issues at the intersection of policing and health,” said lead author Maayan Simckes, a recent doctoral graduate from UW’s Department of Epidemiology who worked on this study as part of her dissertation.

So, Simckes said, she set out to create a conceptual model depicting the complex relationship between policing and population health and assembled an interdisciplinary team of researchers to collaborate.

“This model shows how different types of encounters with policing can affect population health at multiple levels, through different pathways, and that factors like community characteristics and state and local policy can play a role,” said Simckes, who currently works for the Washington State Department of Health.

The study, published in early June in the journal Social Science & Medicine, walks through the various factors that may help explain the health impacts of policing by synthesizing the published research across several disciplines.

“This study provides a useful tool to researchers studying policing and population health across many different disciplines. It has the potential to help guide research on the critical topic of policing and health for many years to come,” said senior author Anjum Hajat, an associate professor in the UW Department of Epidemiology

For example, the study points out when considering individual-level effects that “after physical injury and death, mental health may be the issue most frequently discussed in the context of police-community interaction … One U.S. study found that among men, anxiety symptoms were significantly associated with frequency of police stops and perception of the intrusiveness of the encounter.”

Among the many other research examples explored in the new model, the researchers also examine the cyclic nature of policing and population health. They point out that police stops tend to cluster in disadvantaged communities and “saturating these communities with invasive tactics may lead to more concentrated crime.” Consequently, it may be “impossible” to determine whether police practices caused a neighborhood to experience more crime or if those practices were in response to crime. However, the model’s aim is to capture these complex “bidirectional” relationships.

“Our model underscores the importance of reforming policing practices and policies to ensure they effectively promote population wellbeing at all levels,” said Simckes. “I hope this study ignites more dialogue and action around the roles and responsibilities of those in higher education and in clinical and public-health professions for advancing and promoting social justice and equity in our communities.”

Jake Ellison, University of Washington