The mutations that give rise to melanoma result from a chemical conversion in DNA fueled by sunlight—not just a DNA copying error as previously believed, reports a study by Van Andel Institute scientists published today in Science Advances.

The findings upend long-held beliefs about the mechanisms underlying the disease, reinforce the importance of prevention efforts and offer a path forward for investigating the origins of other cancer types.

“Cancers result from DNA mutations that allow defective cells to survive and invade other tissues. However, in most cases, the source of these mutations is not clear, which complicates development of therapies and prevention methods,” said Gerd Pfeifer, Ph.D., a VAI professor and the study’s corresponding author. “In melanoma, we’ve now shown that damage from sunlight primes the DNA by creating ‘premutations’ that then give way to full mutations during DNA replication.”

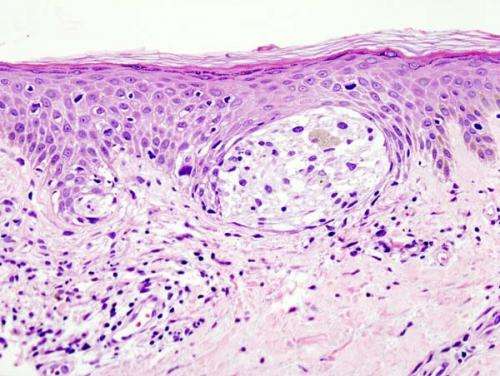

Melanoma is a serious type of skin cancer that begins in pigment-producing skin cells. Although less common than other types of skin cancer, melanoma is more likely to spread and invade other tissues, which significantly reduces patient survival. Previous large-scale sequencing studies have shown that melanoma has the most DNA mutations of any cancer. Like other skin cancers, melanoma is linked to sun exposure, specifically a type of radiation called UVB. Exposure to UVB damages skin cells as well as the DNA within cells.

Most cancers are thought to begin when DNA damage directly causes a mutation that is then copied into subsequent generations of cells during normal cellular replication. In the case of melanoma, however, Pfeifer and his team found a different mechanism that produces disease-causing mutations—the introduction of a chemical base not normally found in DNA that makes it prone to mutation.

DNA comprises four chemical bases that exist in pairs— adenine (A) and thymine (T), and cytosine (C) and guanine (G). Different sequences of these pairs encode all of the instructions for life. In melanoma, the problem occurs when UVB radiation from the sun hits certain sequences of bases—CC, TT, TC and CT—causing them to chemically link together and become unstable. The resulting instability causes a chemical change to cytosine that transforms it into uracil, a chemical base found in the messenger molecule RNA but not in DNA. This change, called a “premutation,” primes the DNA to mutate during normal cell replication, thereby causing alterations that underlie melanoma.

These mutations may not cause disease right away; instead, they may lay dormant for years. They also can accumulate as time goes on and a person’s lifetime exposure to sunlight increases, resulting in a tough-to-treat cancer that evades many therapeutic options.

“Safe sun practices are very important. In our study, 10–15 minutes of exposure to UVB light was equivalent to what a person would experience at high noon, and was sufficient to cause premutations,” Pfeifer said. “While our cells have built-in safeguards to repair DNA damage, this process occasionally lets something slip by. Protecting the skin is generally the best bet when it comes to melanoma prevention.”

The findings were made possible using a method developed by Pfeifer’s lab called Circle Damage Sequencing, which allows scientists to “break” DNA at each point where damage occurs. They then coax the DNA into circles, which are replicated thousands of times using a technology called PCR. Once they have enough DNA, they use next-generation sequencing to identify which DNA bases are present at the breaks. Going forward, Pfeifer and colleagues plan to use this powerful technique to investigate other types of DNA damage in different kinds of cancer.

Van Andel Research Institute