Do Vladimir Putin and Justin Bieber look alike? They do if you think they have similar personalities, shows a new study by a team of psychologists.

Its findings, which appear in the journal Cognition, reveal that knowledge of a person’s personality can influence the perception of a face’s identity and bias it toward unrelated identities. For example, if Vladimir Putin and Justin Bieber, a pair of faces among many tested in the research, have more similar personalities in your mind, then they visually appear more similar to you as well, even if they lack any physical resemblance.

“Our face is another’s portal into our thoughts, feelings, and intentions,” explains Jonathan Freeman, an associate professor in New York University’s Department of Psychology and the paper’s senior author. “If the perception of others’ faces is systematically warped by our prior understanding of their personality, as our findings show, it could affect the ways we behave and interact with them.”

The paper’s other authors were DongWon Oh, a postdoctoral researcher in NYU’s Department of Psychology, and Mirella Walker, a researcher at the University of Basel.

The authors add that the research informs fundamental scientific understanding of how face recognition works in the brain, suggesting that not only a face’s visual cues but also prior social knowledge plays an active role in perceiving faces.

Face recognition is essential to everyday life—in identifying a neighbor at the supermarket, an actor in a film trailer, or a relative in a photograph. And, in recent years, it has been applied to technologies, ranging from the Apple iPhone to extensive counterterrorism and law enforcement applications—with many raising concerns over accuracy.

The Association for Computing Machinery called for a suspension of both private and government use of facial-recognition technology, citing “clear bias based on ethnic, racial, gender, and other human characteristics,” Nature reported last year.

To better understand how our own perceptions—and biases—might influence how we recognize faces, the researchers conducted a series of experiments centering on perceptions of well-known individuals—Bieber, Putin, John Travolta, George W. Bush, and Ryan Gosling, among others (Note: White males were selected in order to establish a racial and gender baseline across tested faces). Racially and ethnically diverse male and female participants were drawn from “Mechanical Turk” (MTurk), a tool in which individuals are compensated for completing small tasks; it is frequently used in running behavioral science studies.

Overall, they found that when a participant believed any two individuals were more similar in personality, their faces were perceived to be correspondingly more similar.

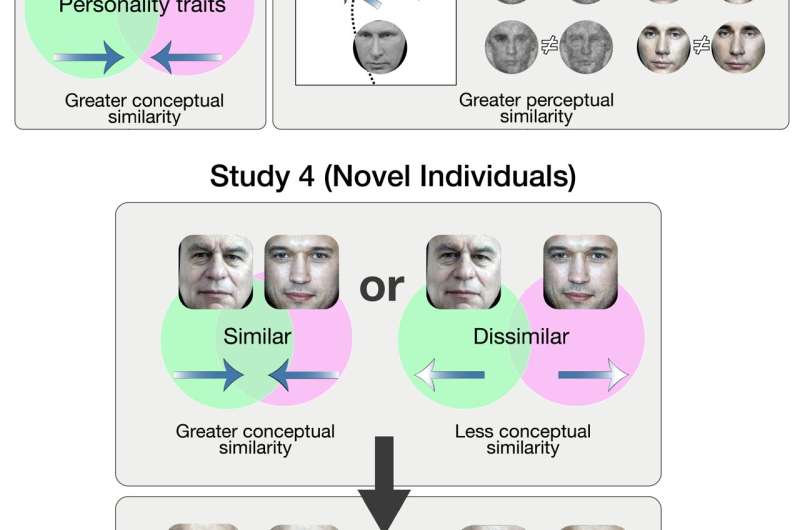

To provide causal evidence, the researchers determined if the effect held for individuals they had never encountered before. The participants viewed images of other White males whom they reported no familiarity with. If the participants learned that these individuals’ personalities were similar (as opposed to dissimilar), their faces were perceived as more visually similar, too.

The researchers used several techniques to assess how faces were perceived at a less conscious level. Subjects’ responses were measured with an innovative mouse-tracking software Freeman previously developed; it uses individuals’ hand movements to reveal unconscious cognitive processes. Unlike surveys or ratings, in which test subjects can consciously alter their responses, this technique requires subjects to make split-second decisions, thereby uncovering less conscious tendencies through subtle deflections in their hand-motion trajectory as they move a mouse during experiments. They also used a technique known as reverse correlation, which allowed the researchers to generate face images depicting how participants perceived others “in the mind’s eye.”

“Our findings show that the perception of facial identity is driven not only by facial features, such as the eyes and chin, but also distorted by the social knowledge we have learned about others, biasing it toward alternate identities despite the fact that those identities lack any physical resemblance,” observes Freeman.

New York University