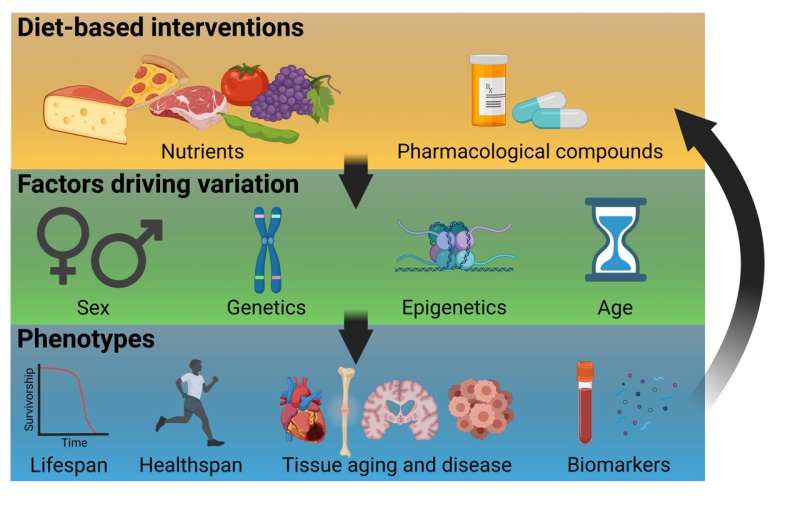

Dietary restriction is arguably the most promising non-genetic method of extending lifespan and healthspan in many model organisms, including mammals. While researchers scramble to develop interventions that would mimic the benefits of dietary restrictions in humans (who generally have a hard time maintaining Spartan diets), the work from the lab of Buck professor Pankaj Kapahi, Ph.D., suggests that the benefits of dietary restriction often vary among individuals and even in tissues within those individuals. He and his colleagues are challenging the field to change their approach to dietary restriction and aim for precise, individualized interventions. In a review published in Cell Metabolism, they provide a framework for a sub-specialty dubbed precision nutrigeroscience, based on biomarkers affected by genetics, gender, tissue, and age.

“Everyone is hoping for a ‘one size fits all’ intervention when it comes to diet, and work in our lab and several others show that this is simply not going to be the case,” says Kapahi, whose team aims to understand the mechanisms by which nutrient signaling and metabolism influence aging and age-related diseases. “I’ve had to change the way I look at aging. A lot of us get very deep into the minutia of understanding what I call two-dimensional biological pathways, and we are forgetting a whole other dimension which is that these pathways are different in each individual, and within tissues in individual bodies. Context matters and we can’t make real progress in this field without including that. We will end up hurting the field because eventually interventions won’t work and then people will get disappointed.”

Studies in genetically distinct strains of fruit flies showed the need for precision-nutrition

In 2020, Buck postdoc Kenneth Wilson, Ph.D., who is the first author of this review, did a genome-wide analysis of 160 genetically distinct strains of the fruit fly D. melanogaster that ate the same Spartan diet. Publishing in Current Biology, he and his team showed that lifespan and healthspan were not linked under dietary restriction. While 97 percent of strains showed some lifespan or healthspan extension on the limited diet, only 50 percent showed a significantly positive response to dietary restriction for both. Thirteen percent of the strains were more vigorous, yet died sooner with dietary restriction; 5 percent lived longer but spent more time in poor health. The remaining 32 percent of the strains showed no benefits or detriments to lifespan or healthspan, or negative responses to both.

“I think it’s important for everyone in the field to understand and appreciate that there are a lot of different ways to look at what an intervention might be doing. You might see a response in one case, but that response might not work in another strain of the same species,” says Wilson. “Conversely if you’re not seeing something, that doesn’t mean that the intervention you’re testing doesn’t work, it just means you’re not using the right model for that intervention.” Wilson says it is also crucial that researchers be aware of the possible disconnect between extending lifespan and healthspan when it comes to diet. “I think the last thing any of us want to do is give people more years of ill health.”

What the review includes

The review provides a detailed primer covering several forms of dietary restriction (from caloric restriction to various forms of intermittent fasting as well as diets that restrict proteins, carbohydrates, specific amino acids, micronutrients, and metabolites) and details related effects in yeast, worms, flies, and mice. Researchers explain nutrient-sensing mechanisms such as IGF-1-like signaling, TOR, and AMPK. They discuss metabolic reprogramming regulators including sirtuins and NAD as well as circadian clock regulators. They include the mediating effects of fat and lipid metabolism, proteostasis and autophagy, and the reduction of cellular senescence as well as mitochondrial function.

The authors cover the complexities of measuring aging in response to dietary restriction, explaining how lifespan analysis is used to decipher the mechanisms of dietary restriction, possible gene-specific lifespan responses to dietary interventions, and the role of gender in species that have males and females. The authors also cover the effects and molecular drivers of dietary restriction on disease models in both simple animals and mammals including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, cancer, and neurodegenerative disease. They also provide an overview of the debate between measuring healthspan and lifespan and summarize molecular biomarkers of aging that have been used in studies of dietary restriction.

“We want to give scientists who are entering the field of aging research an overview so they can start separating the forest from the trees when it comes to dietary restriction,” says Kapahi. “We also wanted to discuss the utility in understanding the exceptions to the current paradigm that dietary restriction is beneficial across the board in every species studied while providing light at the end of tunnel. We know that the science is complex, but if we can frame dietary restriction within the context of precision medicine, everything that people are learning in the field will apply to the larger effort which is all about improving and extending human health. Bottom line is that there are no ‘negative’ or ‘positive’ data—we can glean insights from all of it and it will take a large team effort to fully develop precision nutrigeroscience.”

What we know about humans and dietary restriction

The review also includes data on the reported effects of dietary restriction in humans. While current data shows dietary restriction has positive effects on neurodegeneration, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and kidney disease, the authors report that there are indications that restricting the food we eat could lower bone mineral density, leading to osteoporosis.

Researchers say when it comes to normal aging, dietary restriction likely has broad benefits across many physiological systems, but data shows that restrictive diets negatively limit wound healing and could impact our ability to recover from fractures. While muscle preservation is upregulated with dietary restriction, data also shows that muscle growth is inhibited. The authors say exercise could ameliorate those deficits, adding another factor that needs to be considered when studying the effects of dietary restriction. And while data shows that respiratory function is improved with dietary restriction, it also reveals that exercise capacity could go down at the same time.

“The age of the person utilizing dietary restriction is also a factor that needs to be studied and considered,” says Wilson. “It’s been shown that people who are older may not want to limit their dietary intake, especially when it comes to protein which helps preserve muscle mass.”

What about gender?

Kapahi says gender is one of the main factors driving variable responses to dietary restriction, repeating a little-known but apt adage: “When it comes to DNA, human males have more in common with the male chimpanzee than with human females.” He adds that in flies and mice, females are much more responsive to dietary changes than their male counterparts, likely based on the physiological effects on the female reproductive system and its interplay with other systems. He also points out that until recently, most studies in mice and humans disproportionally involved males.

Women are at greater risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Two-thirds of Americans living with the memory-robbing condition are female and experts say that figure can’t be explained by the fact that women tend to live longer than men. Wilson, who now studies neurodegeneration in flies, mice, and human cell cultures, says diet could someday come into play. “It’s been shown that diet can improve neuronal function,” he says. “We’re not sure of all the mechanisms involved in that, but teasing out the connection between gender and dietary restriction will be part of the plan.”

Implications for clinical trials and potential interventions

Kapahi says taking an individualized approach to dietary restriction could result in more targeted and informative clinical trials because researchers could identify and recruit subsets of people more likely to respond to a particular intervention. “There’s a good chance we would be able to increase the number of potential interventions as well,” he says. “There are likely effective therapeutics that already exist that have been discounted because they haven’t tested well in a particular strain or species of model organism. There is a real benefit in giving up the search for a ‘one-size-fits-all’/’magic pill’ solution to the physical problems of aging.”

Kapahi expects that more studies and conferences focusing on precision nutrigeroscience will help the field develop.

Other Buck Institute collaborators include Manish Chamoli and Tyler A. Hilsabeck. Co-authors also include Manish Pandey, Sakshi Bansal, and Geetanjali Chawla, Regional Centre for Biotechnology, Haryana, India.

Buck Institute for Research on Aging