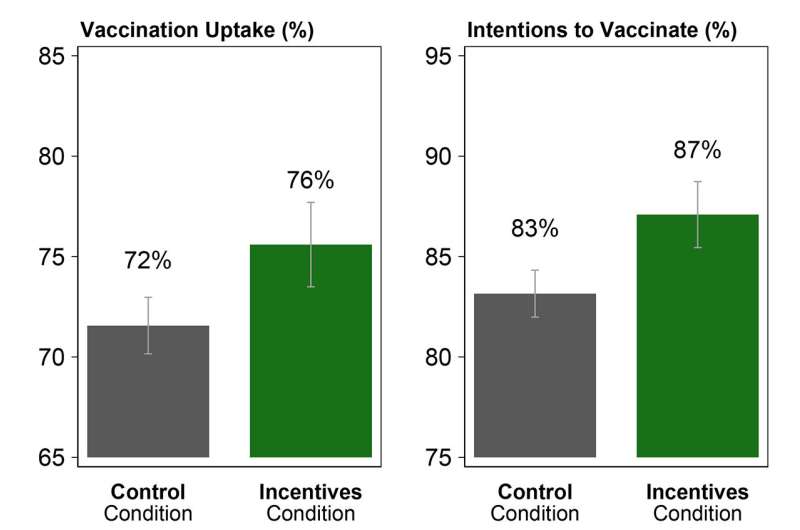

An international study led by Lund University in Sweden has revealed that a small reward of $24 increased the vaccination rate by 4 percent—from 72 to 76 percent. The study involved 8,286 Swedes, and is published in the journal Science.

Around the world, there have been numerous examples of incentives for those who have not yet vaccinated themselves against COVID-19. From supermarkets in the UK offering vouchers, to lotteries in Ohio, and even a call from President Biden that states should pay those who choose to take the shot up to $100. But does it have any effect?

“More Swedes chose to get vaccinated when they were offered a reward of $24. The vaccination rate rose by 4 percentage points,” says Pol Campos-Mercade, postdoc in economics at the University of Copenhagen and one of the researchers behind the study.

The survey is based on a general population sample of 8,286 Swedes between the ages of 18 and 49. In one group, the participants received a payment of $24, provided that they were vaccinated against COVID-19 within 30 days. The vaccination rates were followed up using the Swedish Public Health Agency’s national vaccination register.

The results show that the group that was offered money had a higher vaccination rate compared with the control group. Within 30 days, 76 percent of those offered the payment had been vaccinated, and 72 percent of the participants in the control group.

“We also discovered, somewhat surprisingly, that the vaccination rate rose for everyone, regardless of gender, age and level of education. This indicates that monetary incentives have the potential to increase the rate among people regardless of background. The results also show that the incentives have an effect even in countries with relatively high vaccination levels such as Sweden,” says Erik Wengström, professor of economics at Lund University.

The researchers also touch upon the question: is it worth it? Would it be cost effective for governments to pay people to get vaccinated?

“There is no detailed cost analysis in the study, but it is reasonable to assume that it would be cost-effective for society. The incentives can be considered as a stimulus package, transferring money from the government to people’s pockets, which at the same time would save people’s lives,” says Pol Campos-Mercade.

Another issue that was not examined was whether more money would increase the vaccination rate even further.

“All we can decipher from this is that even with low incentives, we can increase the vaccination rate against COVID-19. The result does not necessarily mean that we should pay people; we do not take a stand on whether it is ethically acceptable to pay people to get vaccinated or not. However, as the pandemic continues, incentives should be one of the tools worth considering in the fight to reduce the spread of COVID-19,” concludes Erik Wengström.

Lund University