A study led by NYU Steinhardt Professor Eric S. Jackson finds that the perception of being heard by a listener plays a key role in whether a person stutters.

The “talk-alone-effect”—the phenomenon in which people who stutter don’t stutter when they are alone—has been noted in anecdotal reports but until now, has not been supported by evidence.

A new study in the Journal of Fluency Disorders, led by NYU Steinhardt Professor Eric S. Jackson explores the talk-alone-effect among people who stutter, and how social pressure and the perception of a listener may influence speech. In the article, “Adults who stutter do not stutter during private speech,” the authors conclude that the talk-alone-effect is real and that the perception of being heard by a listener plays a key role in whether a person stutters.

“There is a lot of anecdotal evidence that people who stutter don’t stutter when talking alone, but this phenomenon has not been confirmed in the lab, mainly because it’s difficult to create conditions in which people believe that they are truly alone,” says Jackson.

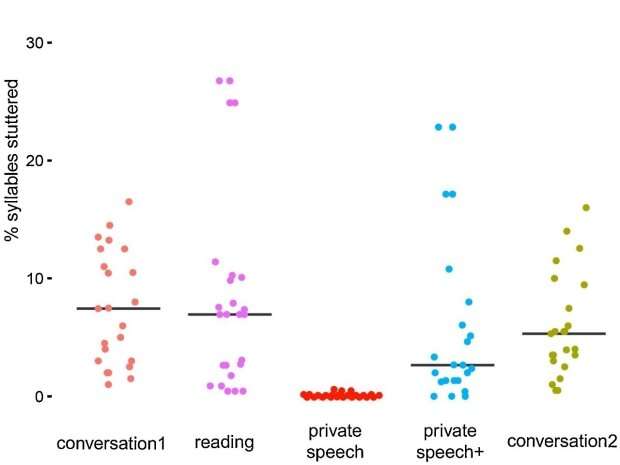

The researchers evaluated 24 adults under five different conditions: conversational speech, reading aloud, private speech (in which participants were made to think no one was listening), repeating the private speech for two listeners, and spontaneous speech. With the exception of private speech, all conditions involved participants talking or reading to others.

In the private speech condition, participants were left alone to complete a challenging computer programming task, which has been shown to elicit private speech in previous studies. Participants were also deceived into thinking that nobody was listening to them, and were told that people who talk out loud to themselves are more likely to perform better on the task.

The private speech condition was the only condition in which instances of stuttering were non-existent.

The study, including the methods of deception, was approved by the Institutional Review Board at NYU. All participants were informed of the deception component after its conclusion and consented to continuing the experiment.

“We developed a novel method to convince participants that they are alone—that their speech wouldn’t be heard by a listener—and found that adult stutterers do not stutter under these conditions. I think this provides evidence that stuttering isn’t just a “speech” problem, but that at its core there must be a strong social component,” Jackson says.

According to Jackson, the presence or possibility of a listener introduces the possibility that the speaker will be evaluated socially. When a speaker is speaking privately, there is no social component, and therefore, the speaker is not concerned with perception or judgment.

The authors outline future directions for research on stuttering and suggest that examining private speech in young children would offer significant insight into the stages at which social considerations begin to influence stuttering.

New York University