It may be worth exploring further the use of cannabidiol (‘CBD’) oil as a potential lung cancer treatment, suggest doctors in BMJ Case Reports after dealing with a daily user whose lung tumour shrank without the aid of conventional treatment.

The body’s own endocannabinoids are involved in various processes, including nerve function, emotion, energy metabolism, pain and inflammation, sleep and immune function.

Chemically similar to these endocannabinoids, cannabinoids can interact with signalling pathways in cells, including cancer cells. They have been studied for use as a primary cancer treatment, but the results have been inconsistent.

Lung cancer remains the second most common cancer in the UK. Despite treatment advances, survival rates remain low at around 15% five years after diagnosis. And average survival without treatment is around 7 months.

The report authors describe the case of a woman in her 80s, diagnosed with non-small cell lung cancer. She also had mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), osteoarthritis, and high blood pressure, for which she was taking various drugs.

She was a smoker, getting through around a pack plus of cigarettes every week (68 packs/year).

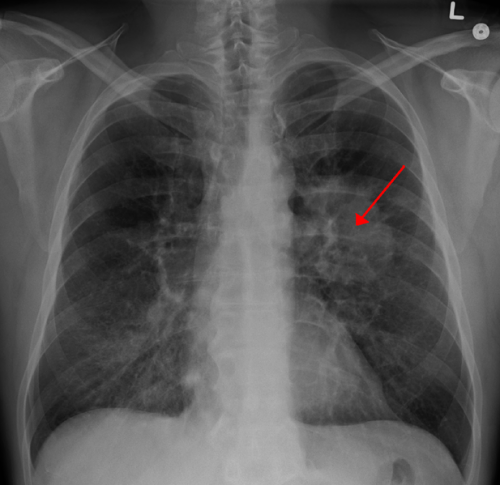

Her tumour was 41 mm in size at diagnosis, with no evidence of local or further spread, so was suitable for conventional treatment of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. But the woman refused treatment, so was placed under ‘watch and wait’ monitoring, which included regular CT scans every 3-6 months.

These showed that the tumour was progressively shrinking, reducing in size from 41 mm in June 2018 to 10 mm by February 2021, equal to an overall 76% reduction in maximum diameter, averaging 2.4% a month, say the report authors.

When contacted in 2019 to discuss her progress, the woman revealed that she had been taking CBD oil as an alternative self-treatment for her lung cancer since August 2018, shortly after her original diagnosis.

She had done so on the advice of a relative, after witnessing her husband struggle with the side effects of radiotherapy. She said she consistently took 0.5 ml of the oil, usually three times a day, but sometimes twice.

The supplier had advised that the main active ingredients were Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) at 19.5%, cannabidiol at around 20%, and tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA) at around 24%.

The supplier also advised that hot food or drinks should be avoided when taking the oil as she might otherwise feel stoned. The woman said she had reduced appetite since taking the oil but had no other obvious ‘side effects’. There were no other changes to her prescribed meds, diet, or lifestyle. And she continued to smoke throughout.

This is just one case report, with only one other similar case reported, caution the authors. And it’s not clear which of the CBD oil ingredients might have been helpful.

“We are unable to confirm the full ingredients of the CBD oil that the patient was taking or to provide information on which of the ingredient(s) may be contributing to the observed tumour regression,” they point out.

And they emphasise: “Although there appears to be a relationship between the intake of CBD oil and the observed tumour regression, we are unable to conclusively confirm that the tumour regression is due to the patient taking CBD oil.”

Cannabis has a long ‘medicinal’ history in modern medicine, having been first introduced in 1842 for its analgesic, sedative, anti-inflammatory, antispasmodic and anticonvulsant effects. And it is widely believed that cannabinoids can help people with chronic pain, anxiety and sleep disorders; cannabinoids are also used in palliative care, the authors add.

“More research is needed to identify the actual mechanism of action, administration pathways, safe dosages, its effects on different types of cancer and any potential adverse side effects when using cannabinoids,” they conclude.

British Medical Journal