A government advisory committee on Wednesday recommended that all U.S. adults younger than 60 be vaccinated against hepatitis B, because progress against the liver-damaging disease has stalled.

The decision means that tens of millions of U.S. adults—mostly between the ages of 30 and 59—would be advised to get shots. Hepatitis B vaccinations became standard for children in 1991, meaning most adults younger that 30 already are protected.

“We’re losing ground. We cannot eliminate hepatitis B in the U.S. without a new approach,” said Dr. Mark Weng of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted unanimously to approve the recommendation Wednesday. The CDC’s director, Dr. Rochelle Walensky, must sign off on it before it becomes public policy, but it’s not clear when she will decide.

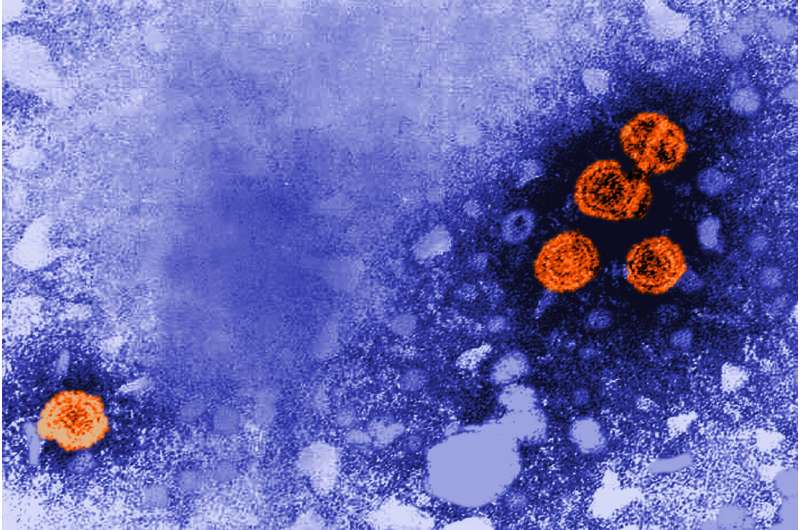

The virus is spread through contact with blood or other bodily fluids and many recent cases have been linked to the opioid epidemic.

An estimated 1.9 million Americans are living with hepatitis B infections, though many may not experience liver damage and accompanying symptoms for many years. The government has set a goal of eliminating viral hepatitis as a threat by 2030.

Officials previously recommended shots only for adults who fall into 15 categories of risk—a list that includes prisoners, health care workers, international travelers, patients with diabetes and certain other conditions, and people who inject drugs or who have multiple sexual partners.

Health officials estimate about 20,000 new infections occur each year. The rate has been generally flat, though it has been rising in Americans in their 40s and 50s, officials said.

“The current risk-based strategy … has taken public health as far as it can take us,” said Dr. Kevin Ault, a committee member who chairs a work group focused on hepatitis vaccines.

The shots are given in either two or three doses, spaced a month or more apart. CDC data suggests that only about one-third of the at-risk people with diabetes and chronic liver conditions have been vaccinated, and just two-thirds of eligible health-care workers. Overall, about 30% of all adults are vaccinated.

The committee considered recommending the shots for all adults. But a slight majority of members voted to set a ceiling age of 59 on the recommendation—because it echoes the parameters of the previous recommendation for people with diabetes.

They argued that many elderly people are not at risk for infection, and that money and resources spent on vaccinating the elderly would have diminishing returns on reducing infections.

Under existing policy, people 60 and older can get the shots if they wish.

Mike Stobbe